Ben Eater 8-bit computer project

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

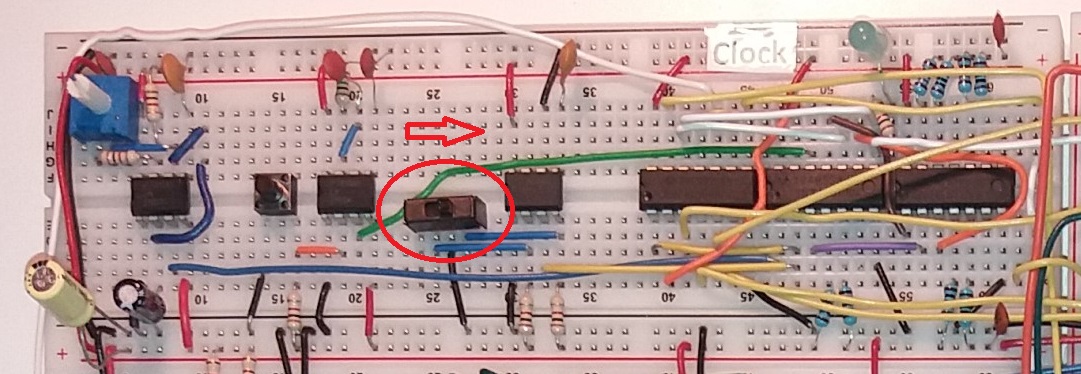

- Clock

- Registers

- Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU)

- Random Access Memory (RAM)

- Register recap

- Difference between registers and memory

- Address decoder

- 74LS189 (16 4-word address RAM)

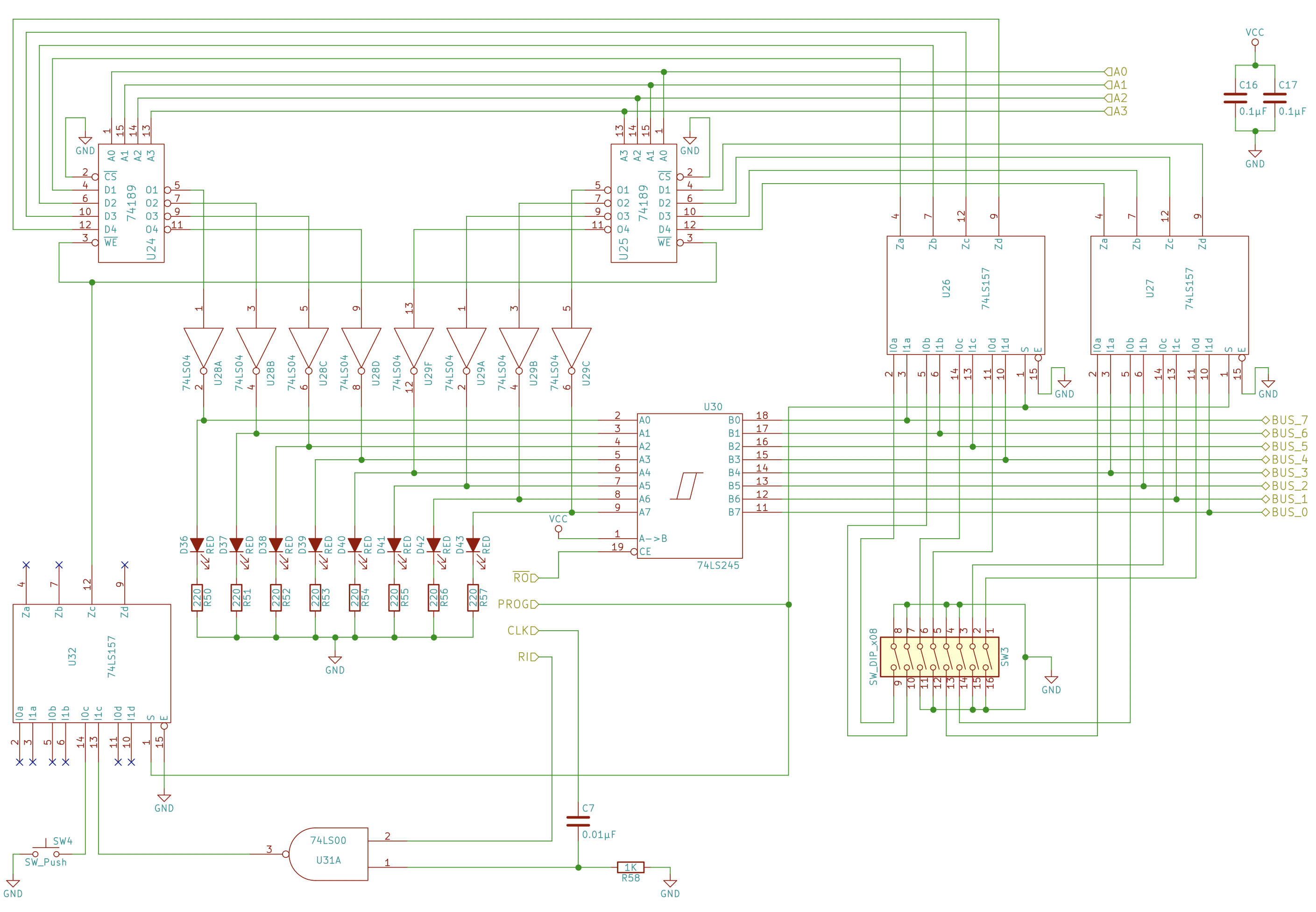

- Building the RAM

- Building the memory address register (and a “programming mode” version)

- Building an 8-bit input terminal for the RAM (to manually store a program) and the alternative of inputs from the Bus

- Testing the RAM

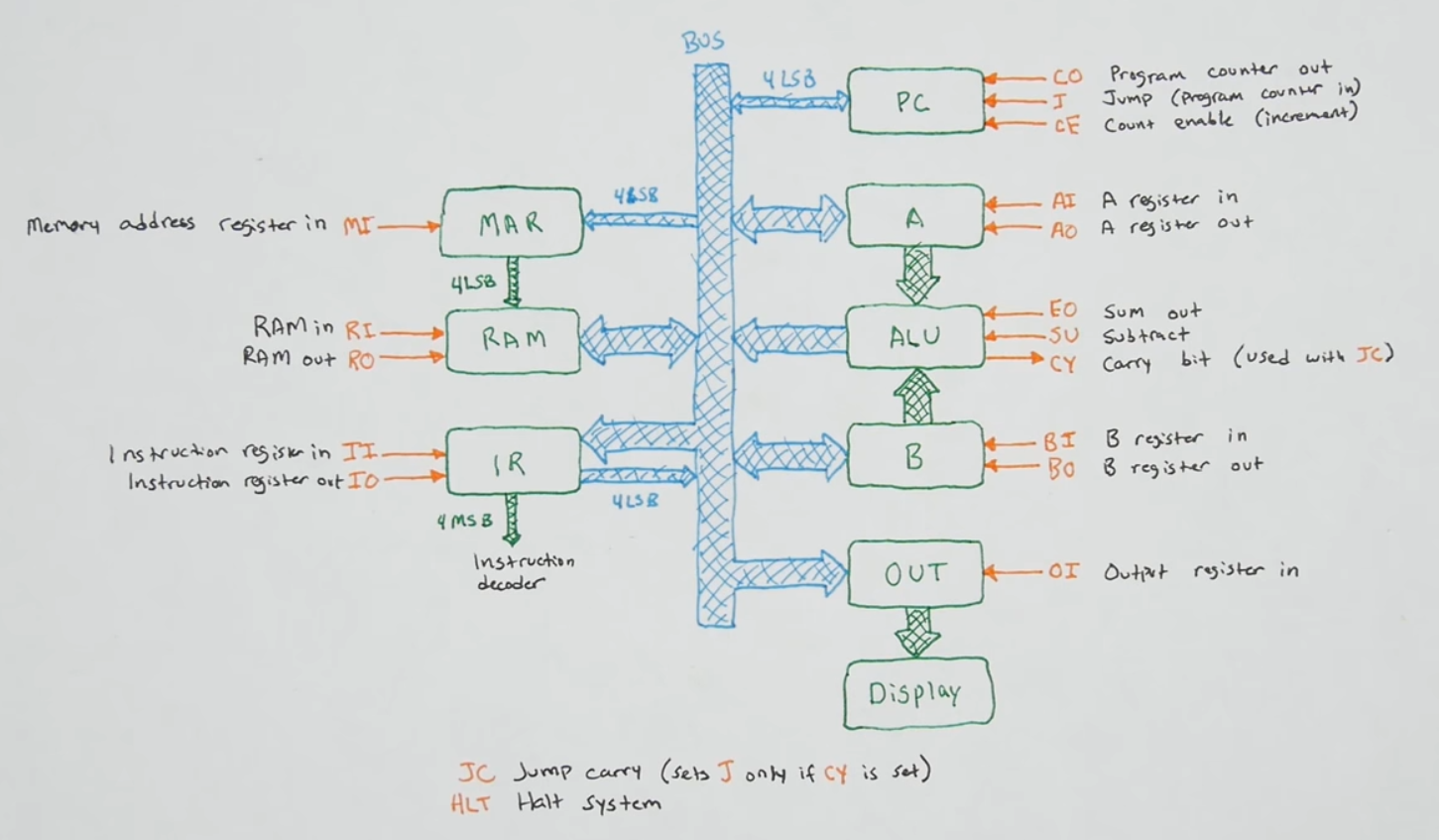

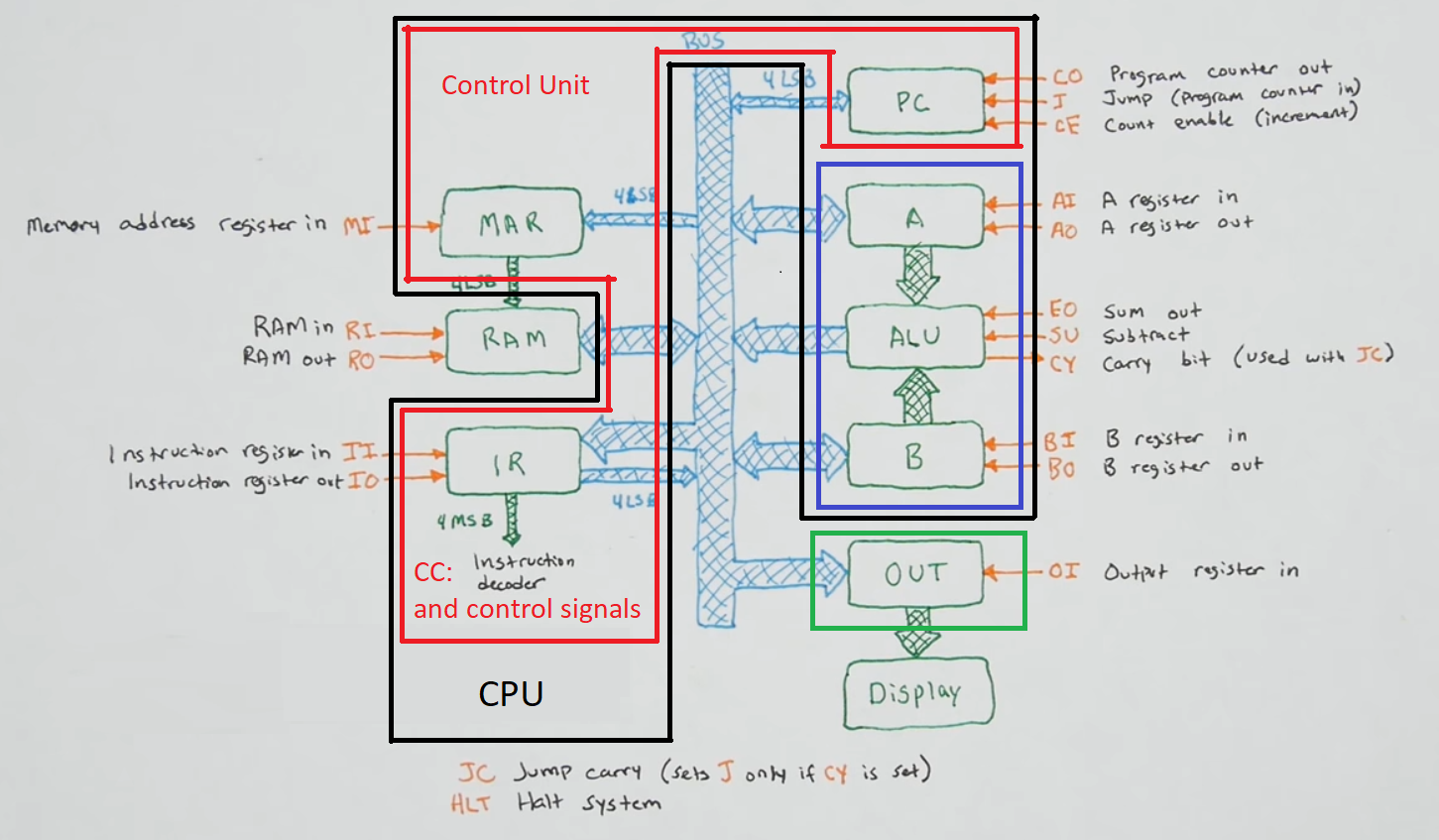

- Labeling jumperwires (control signals) and architecture overview

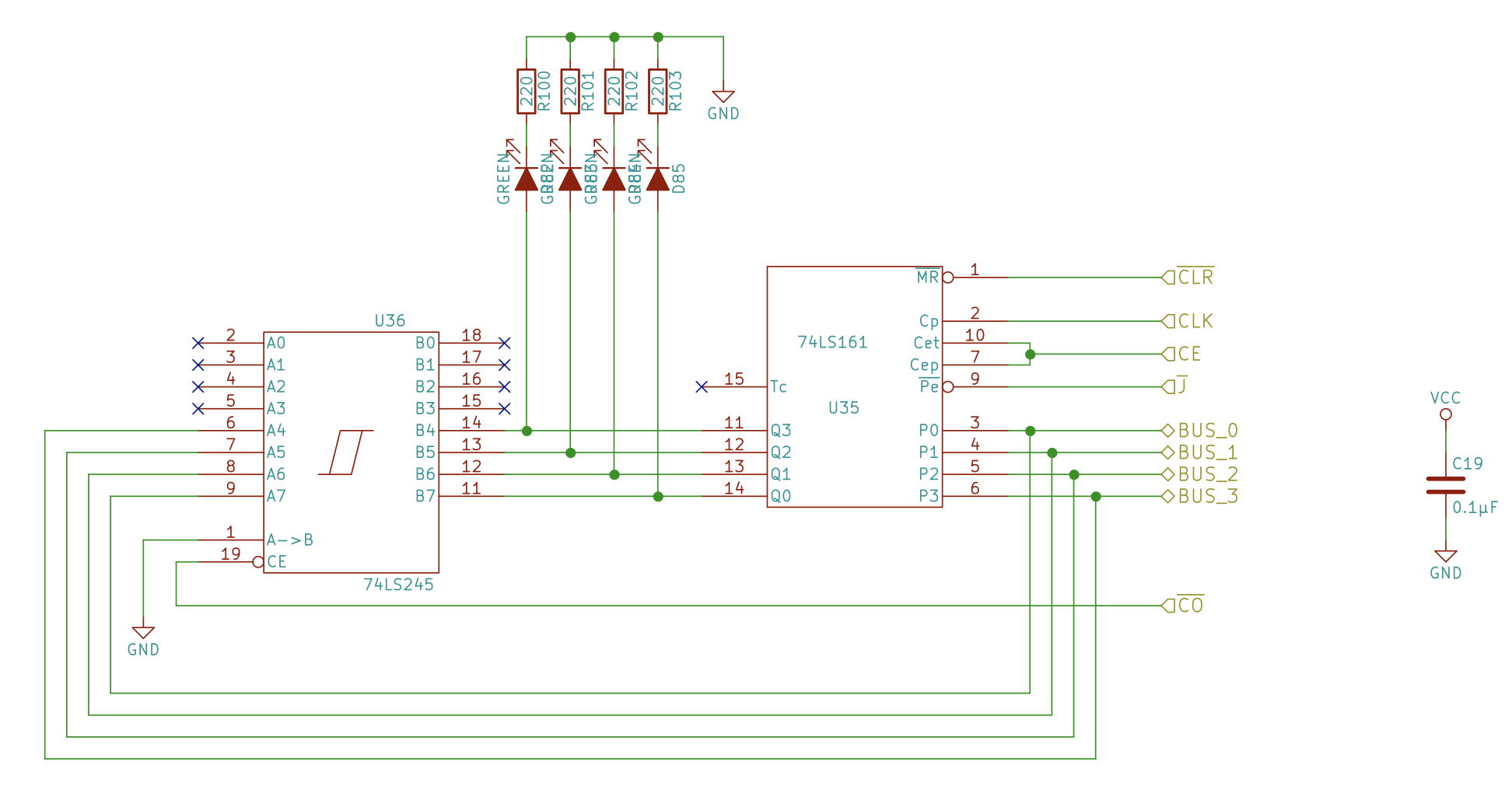

- Program counter (PC)

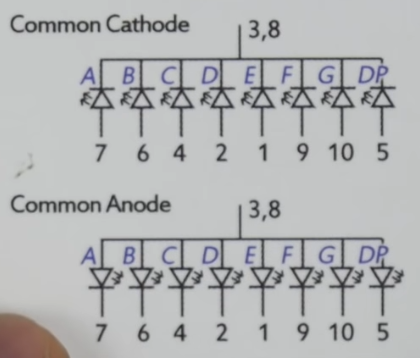

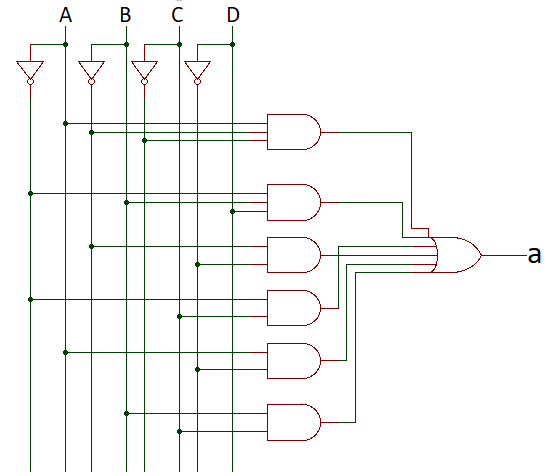

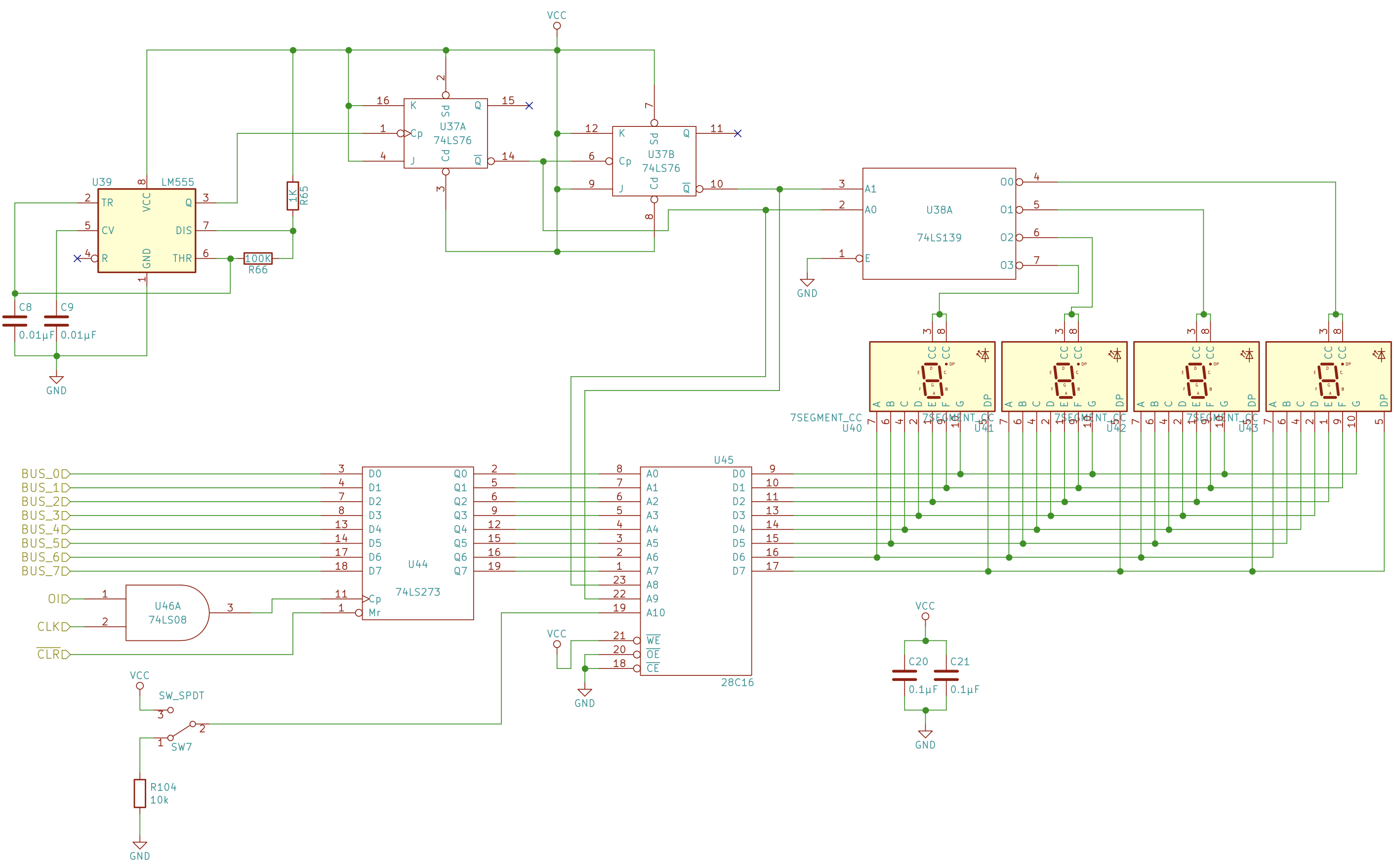

- Output module

- Terminology review

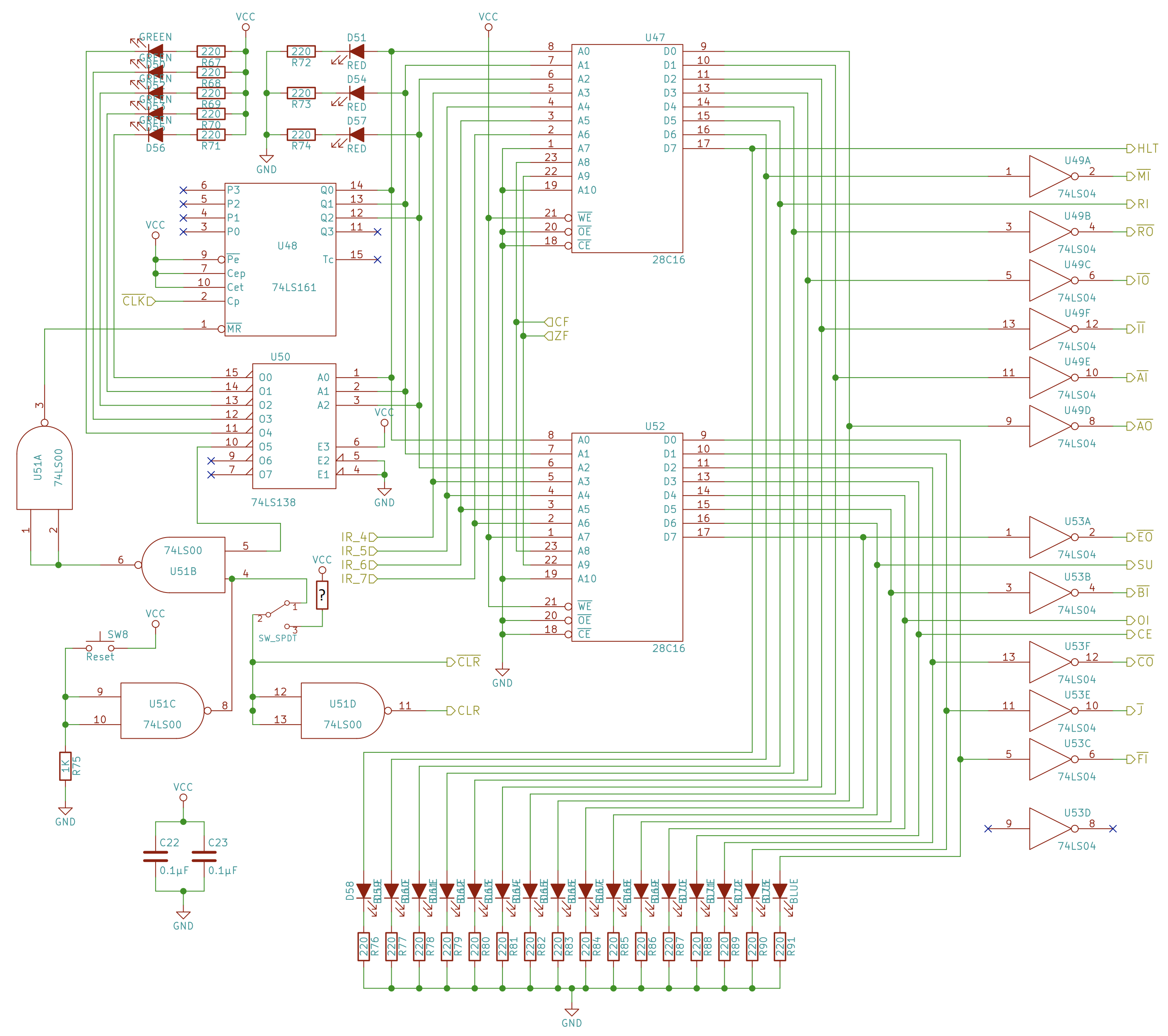

- Control unit

- Last minute fixes

- Programs

Introduction

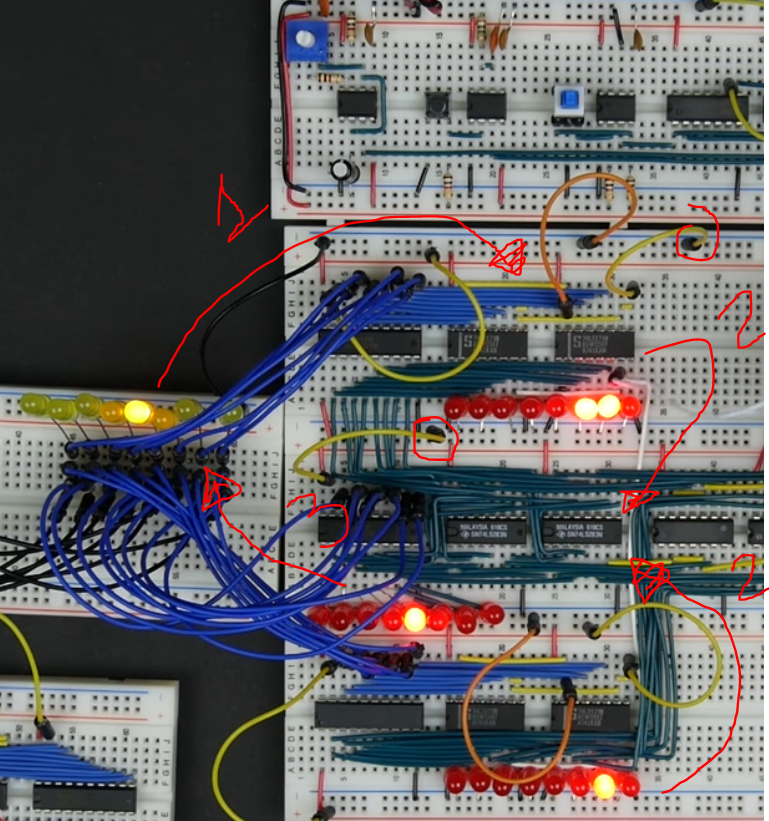

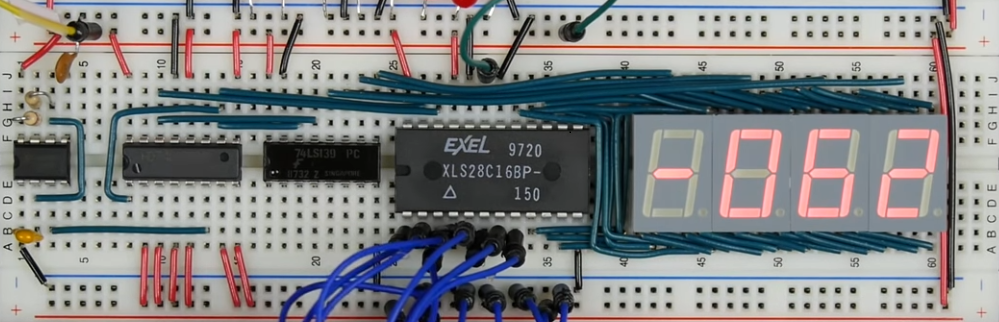

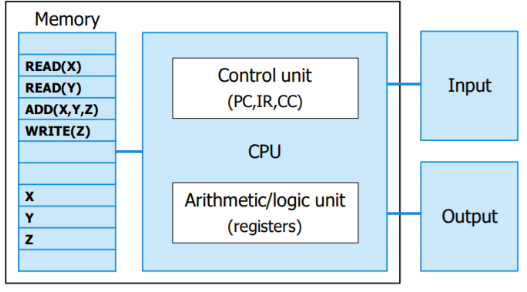

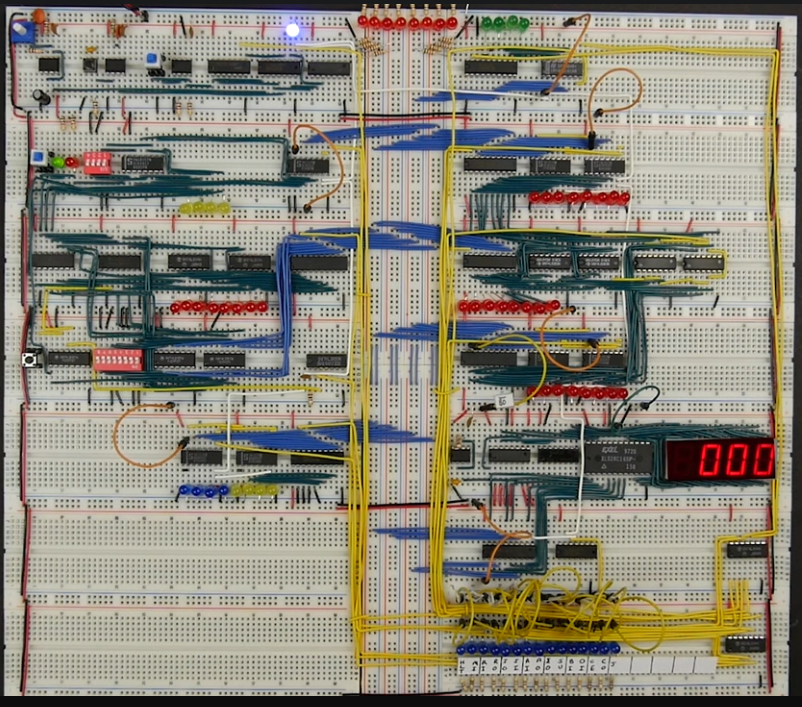

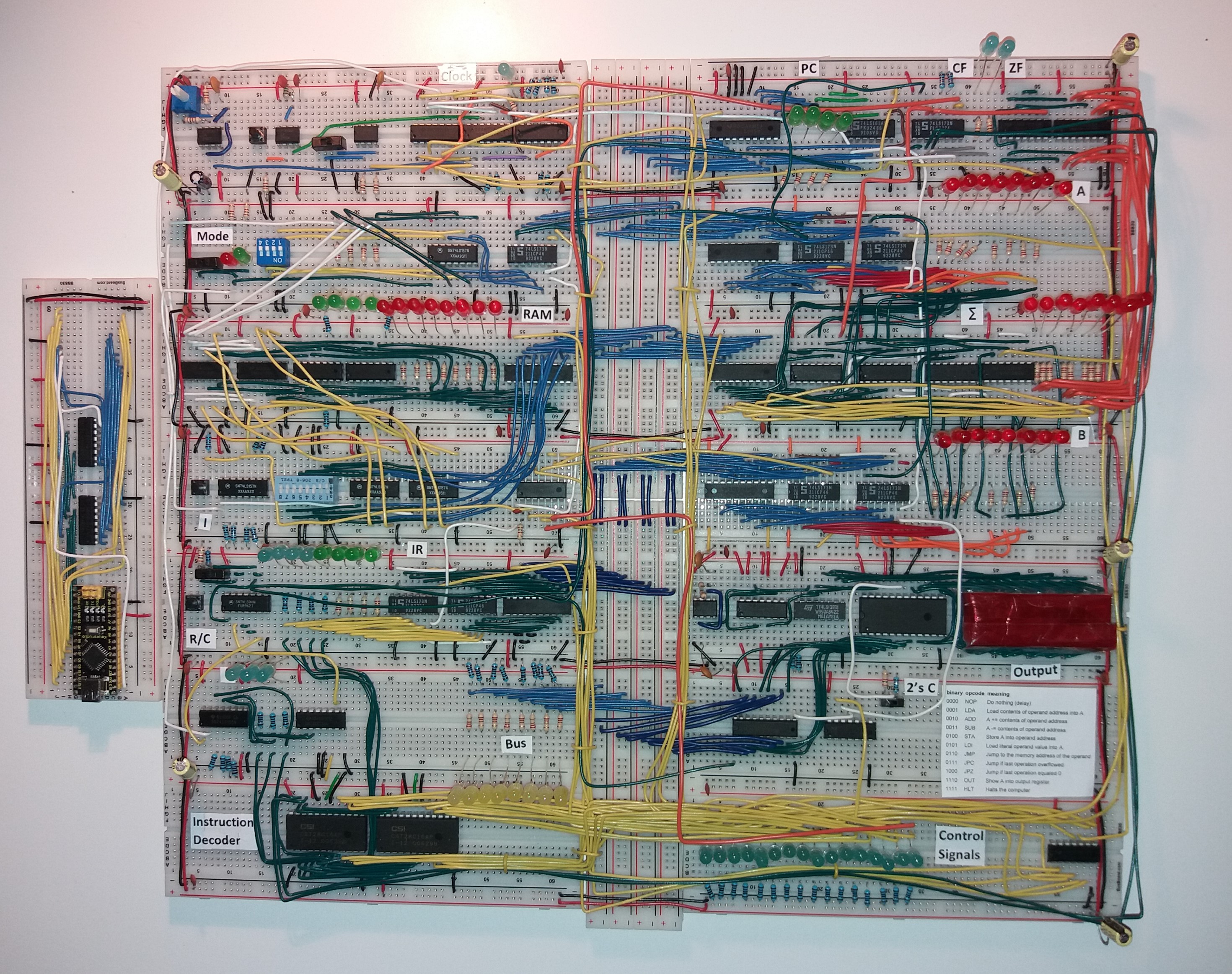

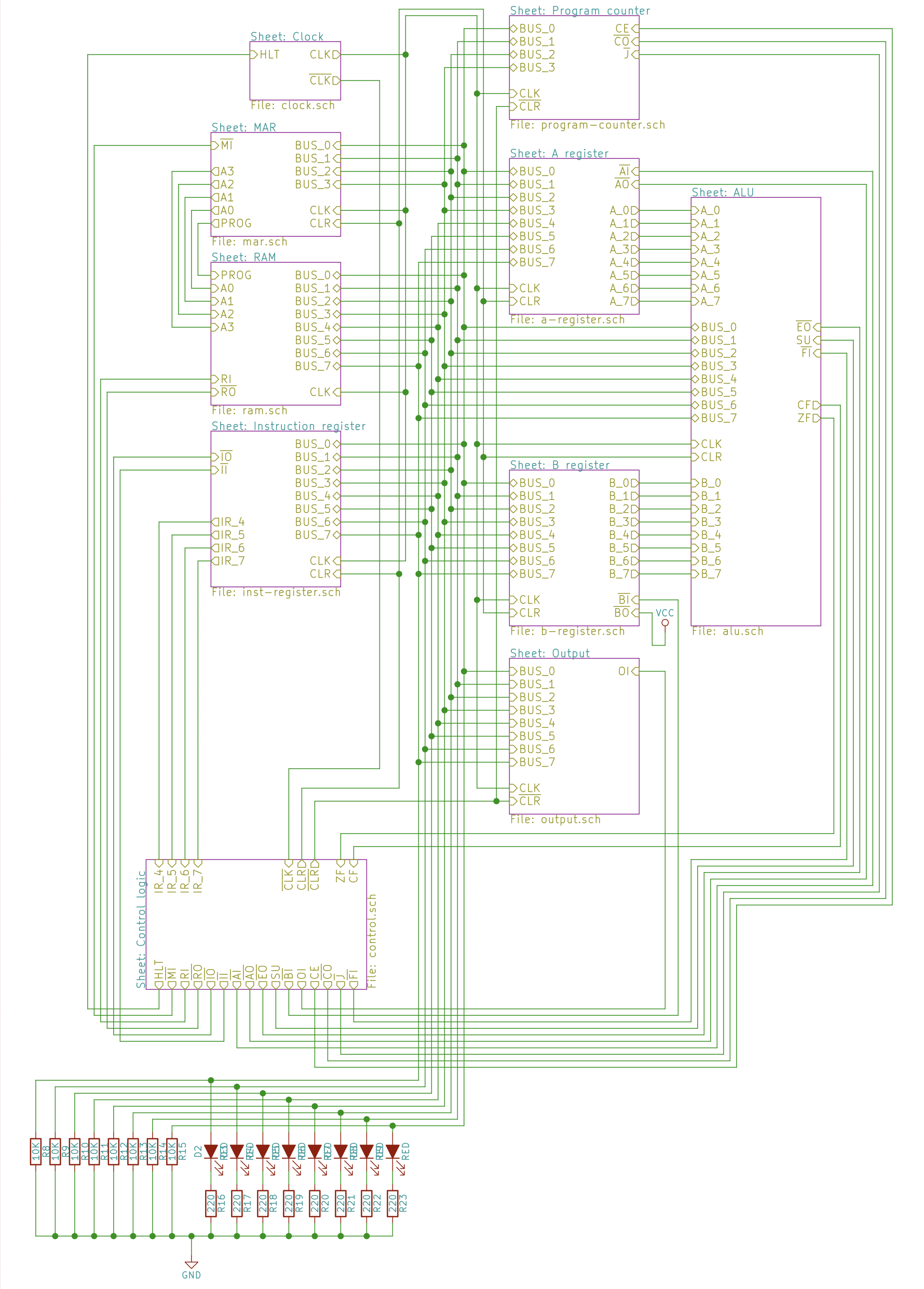

Ben Eater is an online educator on computer-related topics from which I’m following his 8-bit computer project. https://eater.net/8bit. The computer is composed of different modules, which are built on breadboards. The modules are the clock module, registers and ALU (arithmetic and logic unit) module, RAM (random access memory) and program counter module, and output and control logic module.

- To refresh circuit analysis basics check this post.

- You can also check my CSE1400 Computer Organization notes

Computer features

- Specsheet

- How to operate:

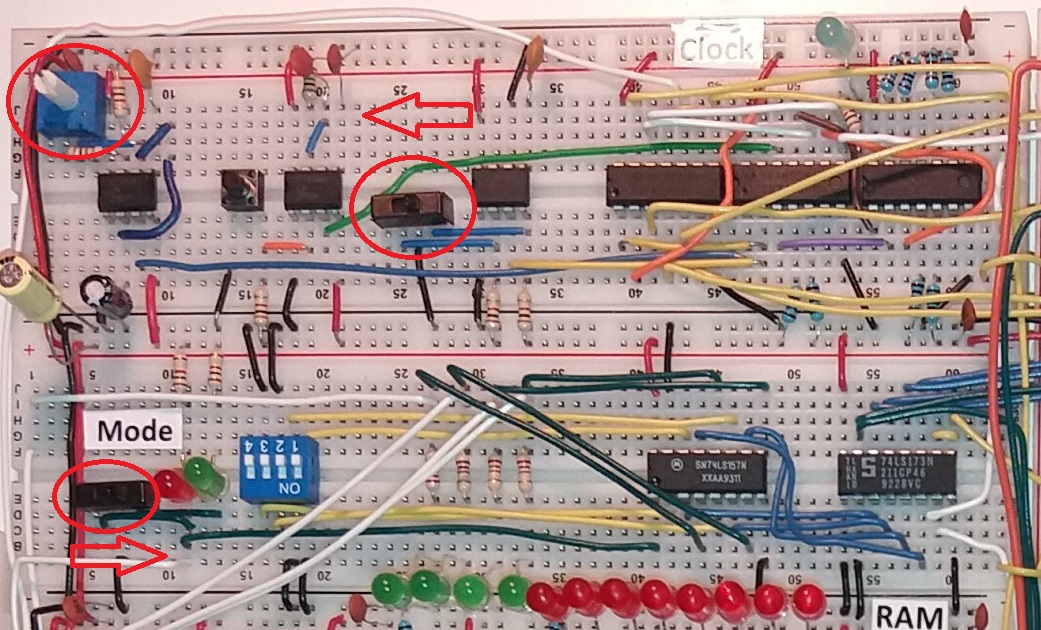

- Set clock to monostable by moving the slideswitch to the right (manual clock pulse)

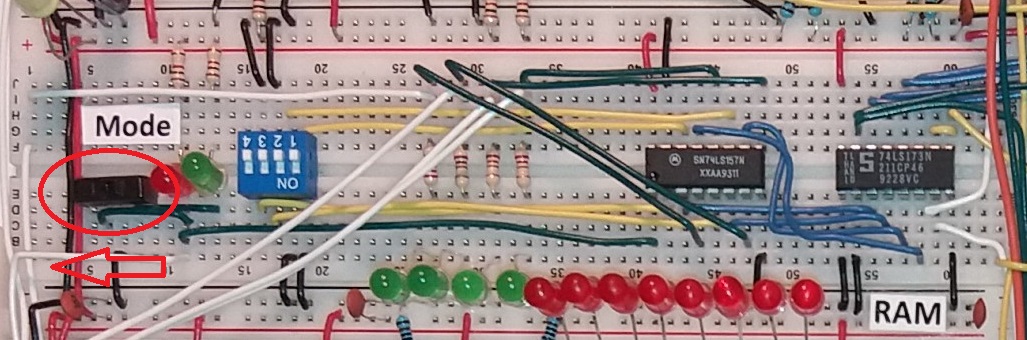

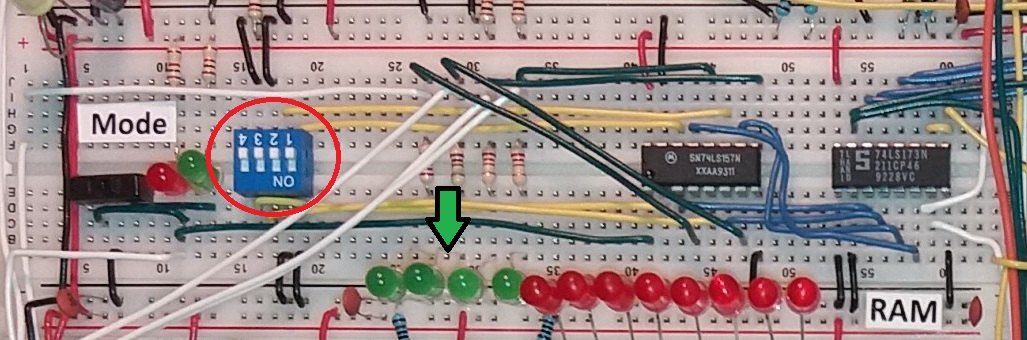

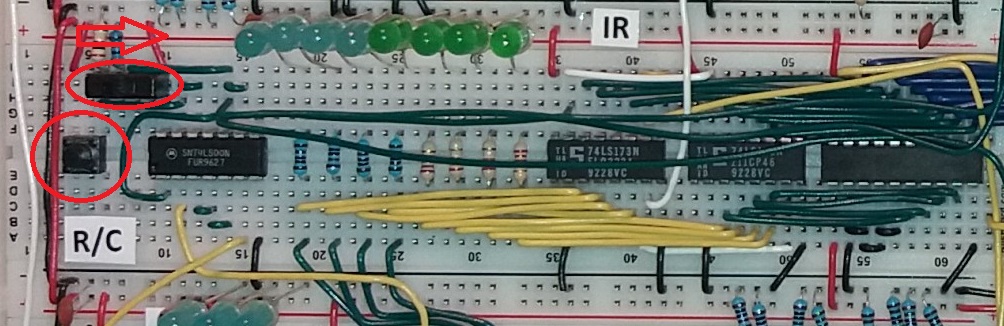

- Set mode to programming mode with the slide switch (left = red led on = programming mode)

- Use the 4-bit DIP switches to change the address of the RAM

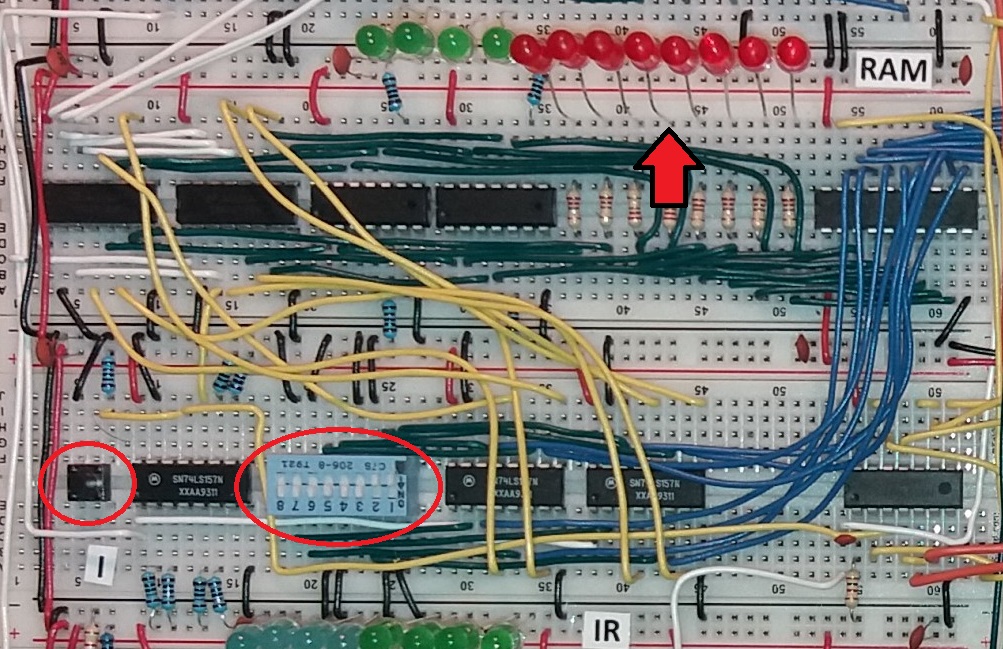

- Use the 8-bit DIP switches to set the contents of the RAM and press the Input button (I) to save them

- Reset all registers and counters with the R/C button with the “clear” switch on (to the right)

- Set the computer back to run mode (slide switch to right = green led on = run mode), and set the clock to astable by moving the slideswitch to the left and adjust the speed with the potentiometer

- Set clock to monostable by moving the slideswitch to the right (manual clock pulse)

- Use this assembly language for your programs, this compiler to turn it into binary and you may as well use this forked repo to simulate the program execution

- Fibonacci demo:

- The computer is “turing complete” because it allows the execution of a program and the computer supports addition, subtraction and conditional jumps, from which any computable problem, given infinite memory, could be computed.

Power supply

We will be using a 5V (volt) power source, which Ben has crafted by cutting off the wires of a cellphone charger.

- Safety rules before using anything related to electricity:

- Dont plug a lot of stuff into a single extension cord

- Keep eletrcical things far away from water

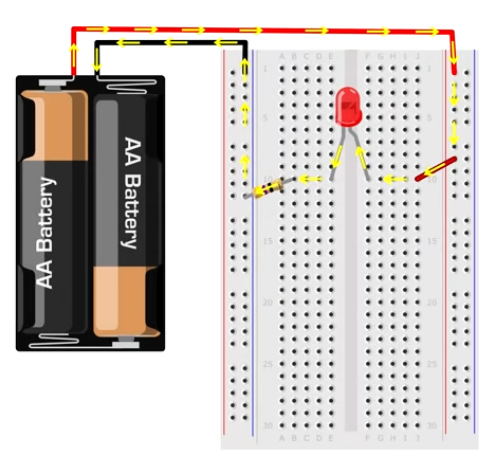

- Never connect LEDs directly to 5 volt source without a current limiting resistor or you will damage the LED.

- Most 74LSxx logic chips have internal resistors that let you connect LEDS directly to the outputs without a resistor. However, the 555 timer, 74189 RAM, 28C16 EEPROM and 74HC595 do not.

- For most reliable results you may want to connect a \(220\Omega\) resistor in series with every LED.

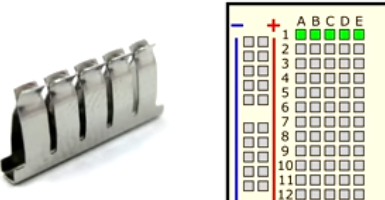

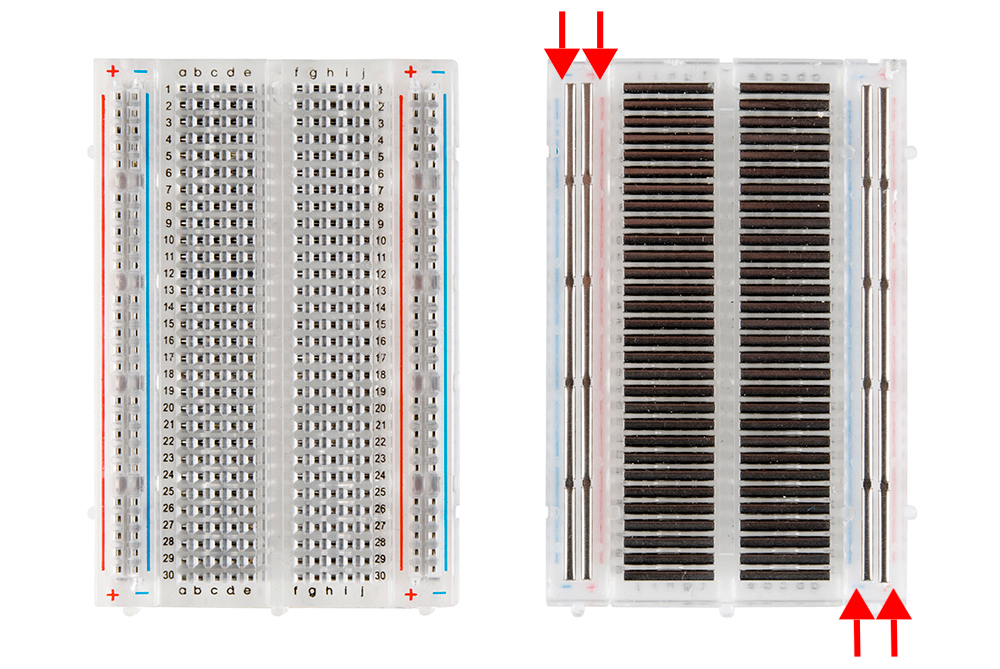

Breadboards

- The breadboard is composed of metalical strips that can be linked together with jump wires and electrical components.

- The A-J holes constitute columns (each) and the numbers constitute rows.

- A1, B1, C1, D1 and E1 are all connected, and not connected to any other wholes in the breadboard.

- The individual power buses are not connected to each other (only the column itself).

- The + - vertical strips are called buses or rails and are used to deliver power.

- The red (+) line will connect to the positive terminal of the battery

- The black or blue (-) line will connect to the negative terminal of the battery

- The busline may not connect the entire length of the board, unbroken lines show that the bus indeed connects the entire length

- The middle space of the breadboard is designed to fit the integrated circuits (IC) (chips) that come with dual in-line package (DIP), meaning they come in two columns of pins of which each individual pin is connected to its own row.

Sample closed circuit

- The long leg is the positive side of the LED and it’s called anode, and the shorter leg is for the negative side and it’s called cathode.

- Plugging it backwards wont break the led, but it will block the current flow of the circuit.

Common mistakes

- Setting the LD legs in different rows

- Loose wires not pushed deep into the wholes

- Disrespecting the polarity of the components

- LEDs have polarity: long leg +, short leg -

- Resistors don’t have polarity

- Jumper wires:

- Long flexible wires are convinient for simple circuits but will spagetti-like mess up complex circuits

- Pre-cut wires have predefined lengths which limit customization

- hookup wire and wire strippers to make your own wires:

- Make sure to buy solid-core wire and not stranded wire as the latter is made up of multiple individual strands which makes the ends much harder to push into a breadboard

- As a last resort if stranded wired cannot be solded it can be twisted to increase its tightness.

- To leave enough space for bending the wires and plug them into the board leave a room of 3 more wholes.

- Integrated circuits:

- Not connecting an integrated circuit in the middle of the board as that will connect both ends of the IC (making a shortircuit)

Disclaimers

IC numbers and logic families

For example, let’s break down SN74LS161A.:

- SN - these prefixes typically just tell you what manufacturer it is. For example, SN is used by Texas Instruments. As far as I know, you can ignore this.

- 74 - denotes that it’s a standard consumer chip. There are a few other types, like military and automotive

- LS - this is the logic family. Do not mix chips from different logic families unless you know they are compatible (i.e. LS and HCT)

- LS - Low-power schottky. Built with transistor-transistor logic (TTL). What Ben uses. Old. Not really that low-power compared to newer chips. Pretty damned resilient. Not compatible with HC.

- HC - CMOS. Uses much less power. A bit less forgiving and not compatible with LS or other TTL chips.

- HCT - A special kind of CMOS designed to work with TTL chips.

- You may also find chips without a logic family (i.e. 74161). They are regular TTL chips.

- 161 - the actual chip number. This one is a synchronous 4-bit binary counter.

- A - this depends on the chip, but may denote the form factor - i.e. 40-pin DIP. Information may be in the datasheet.

Pulling resistors

- Pull-up and Pull-down resistors are used to correct bias the inputs of digital gates to stop them from having inpredctable high/low values when there is no input condition.

- If you tie a pin to VCC with a resistor, it’s said to be “pulling the pin up”, and if you tie it to GND it’s “pulling the pin down”, hence the terms pull-up and pull-down.

- Unused LS-series inputs should typically be tied in a way such that the corresponding output is always high. (this is to consume less power, the arch-rival of the project)

- Some of the push buttons also need resistors so that they aren’t “floating” when they’re disconnected. For example, I added a 1K pull-up to the RAM write button.

- Some chips families are less forgiving about floating inputs, so as a thumb rule you should never leave an input pin unconnected (floating).

- An open CMOS input pin is in a “high impedance” state, which means there won’t be any substantial opportunity for a charge built up on the pin to dissipate and the Voltage of the pin will drift around due to internal and external leakage.

- In TTL 74LS serie, a input signal between 0 and 0.8V is considered “LOW”, and a input signal between 2.0 and 5.0V is considered “HIGH”. Any voltage between 0.8 and 2.0 volts is undefined. Therefore, you have to guarantee in your design that you will never enter in the uncertainty zone.

- A Ben follower suggested to use 10k resistors, other suggested 1k, also for the Bus default pull-down resistors (instead of the 10k of Ben’s build). So use 10k for pull-up and 1k for pull-down.

- But there’s actually an accurate way to calculate them

- Connecting directly to VCC (or even ground) might be a bad idea because a high current will flow through the pull-up resistor, heating the device and using up an unnecessary amount of power when the switch is closed. So the idea is to calculate the MAX resistor value, and then round it down to the nearest standard commercial resistor value out there.

- A rule of thumb is to use a resistor that is at least 10 times smaller than the value of the input pin impedance. In bipolar logic families which operate at operating at 5V, the typical pull-up resistor value is 1-5 kΩ. For switch and resistive sensor applications, the typical pull-up resistor value is 1-10 kΩ. If in doubt, a good starting point when using a switch is 4.7 kΩ. Some digital circuits, such as CMOS families, have a small input leakage current, allowing much higher resistance values, from around 10kΩ up to 1MΩ. The disadvantage when using a larger resistance value is that the input pin responses to voltage changes slower.

Max Pull-up Resistor Value

\[Rmax = \frac{V_{CC}-V_{IH(MIN)}}{I_{IH(MAX)}}\]where: \(V_{IH(MIN)}\) is the minimum input voltage guaranteed to be recognized as a logic “1” (2V approx., but see in datasheet). \(I_{IH(MAX)}\) is the max current flows into the TTL input when the input is a ‘HIGH’ (see in datasheet).

If you use a higher resistor, you will have a voltage within the undefined zone.

For the pull-down resistor, the analysis is similar.

Max Pull-down Resistor Value

\[Rmax = \frac{V_{IL(MAX)}-V_{IL(MIN)}}{I_{IL(MAX)}}\]where: \(V_{IL(MAX)}\) is the maximum input voltage guaranteed to be recognized as a logic ‘0’.(0.8V approx., but see in datasheet). where: \(V_{IL(MIN)}\) is the minimum input voltage guaranteed to be recognized as a logic ‘0’. (0V approx., but see in datasheet). \(I_{IL(MAX)}\) is the max current flows into the TTL input when the input is a ‘LOW’ (see datasheet).

Again, if you use a higher resistor, you will have a voltage within the undefined zone.

Power

- The LS series chips are designed to run with no less than 4.75 volts. That gives you very little wiggle room. You absolutely need to have good power distribution.

- Run “main” power rails down both sides of the computer and connect every regular power rail on your computer directly to the main power rails. This will eliminate the daisy-chaining completely and ensure (nearly) optimal power distribution.

- Alternatively connect power rails from left side of the Bus breadboards with right side of the Bus breadboards, at least once for each breadboard.

- Run “main” power rails down both sides of the computer and connect every regular power rail on your computer directly to the main power rails. This will eliminate the daisy-chaining completely and ensure (nearly) optimal power distribution.

- The LS series of chips are TTL (transistor-transistor logic), which use quite a bit of power and are noisy when switching. They can cause voltage fluctuations which can make other chips do strange things.

- A decoupling capacitor sits directly across your power rails and serves to smooth out fluctuations in your power lines.

- Spread the 100nF capacitors (104) accross power rails of the entire project (for every few chips up to 1 capacitor for each chip).

- Put the \(10\mu F\) capacitors at least once on each breadboard

- Try to use BB830 breadoards and 22-gauge wire.

- Often the schematic will ignore the \(V_{cc}\) and ground pins of the chips and you should implicitly take care of those by looking at the datasheet of the chip.

- Use a high quality power adapter. People report to have more reliable results with the Apple iPad adapter than the one that comes with the kit.

LEDs

- Ben Eater videos often don’t have resistors in series with the LEDs because of the LS chip family have limited current outputs.

- In practice LEDs did sink too much current and not adding resistors caused weird behavour for input pins relying on the current from those outputs.

- Ben’s schematic does include resistors.

- Each LED color has a different brightness, and these resistor values will reduce the brightness levels so that they’re similar. Specifically, 2.2k resistors for the red LEDs and 4.7k for the blue.

- (The kits don’t include none of those resistor values)

Sources:

- https://www.reddit.com/r/beneater/comments/dskbug/what_i_have_learned_a_master_list_of_what_to_do/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/beneater/comments/ii113p/helpful_tips_and_recommendations_for_ben_eaters/

Datasheets

- 555 timer

- 74LS00

- 74LS02

- 74LS04

- 74LS08

- 74LS32

- 74LS86

- 74LS107

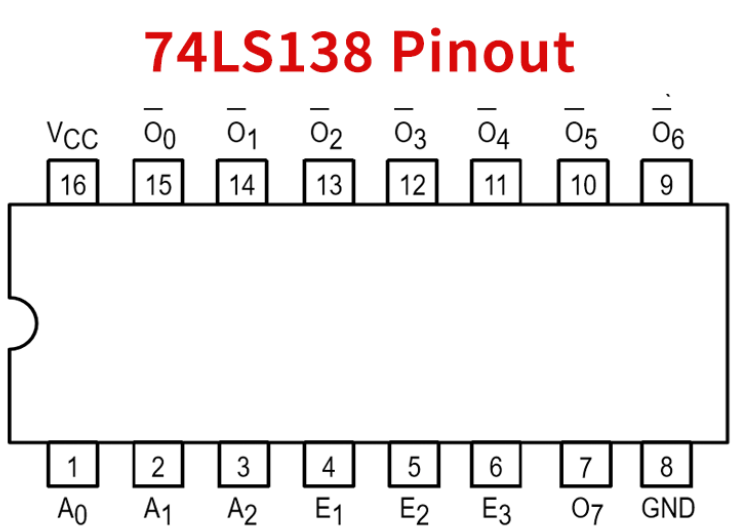

- 74LS138

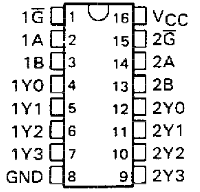

- 74LS139

- 74LS157

- 74LS161

- 74LS173

- 74LS245

- 74LS273

- 74LS283

- 74F189

- 74HC595

- AT28C16

- Capacitor codes

Clock

- Components included in the kit:

- 1 Breadboard

- Great for experiencing circuits, not intended for permanent ones.

- In addition, for the project you’ll need

- jumper wires

- wire strippers

- wire cutters

- needle nose pliers

- 1 Jumper wire kit

- With 140 pre-cut wires

- 1 Power plug

- 1 Power plug adapter

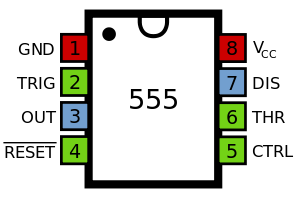

- 3 555 IC timers

- 1 74LS04 hex inverter

- 1 74LS08 quad AND gate

- 1 74LS32 quad OR gate

- 1 Momentary pushbutton

- 1 \(1M\Omega\) potentiometer

- 1 slide switch

- 5 \(220\Omega\) resistors (red-red-brown)

- 10 \(1k\Omega\) resistors (brown-black-red)

- 5 \(1M\Omega\) resistors (brown-black-green)

- 5 Yellow LEDs

- 5 Blue LEDs

- 5 \(0.01\mu F\) capacitors

- 5 \(0.1\mu F\) capacitors

- 5 \(1\mu F\) capacitors

- 5 \(10\mu F\) capacitors

- 1 Breadboard

- The clock coordinates everything, it sets the timing of everything.

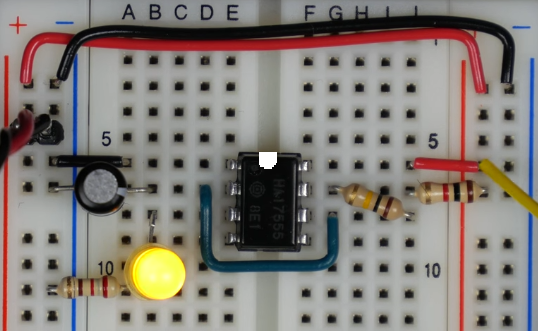

- We are using the 555 timer IC (integrated circuit (chip) below)

- Our clock is adjustable-speed (from less than 1Hz to a few hundred Hz).

- One Hertz (Hz) is defined as one cycle per second

- The clock can also be put into a manual mode where you push a button to advance each clock cycle. (Useful for debugging)

- At this point I’m assuming that the goal of the clock module is to provide an output voltage terminal that alternates between high and low voltage with a frequency between 1-100 Herz. Then use one clock cycle as a unit of time to determine operation slots.

- Slots could be used to synchronise operations (i.e. to ensure that the Bus is only being used by 1 party at a time)

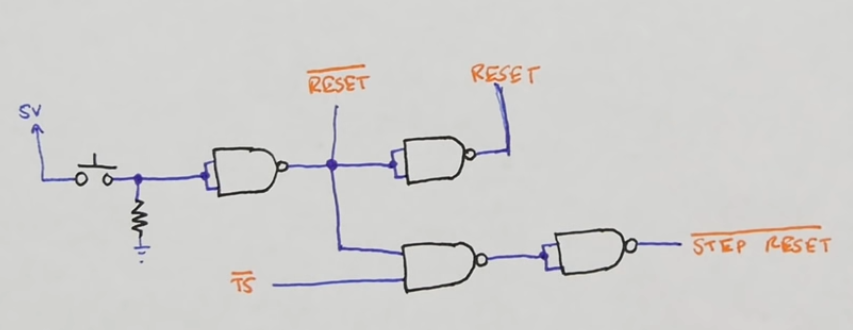

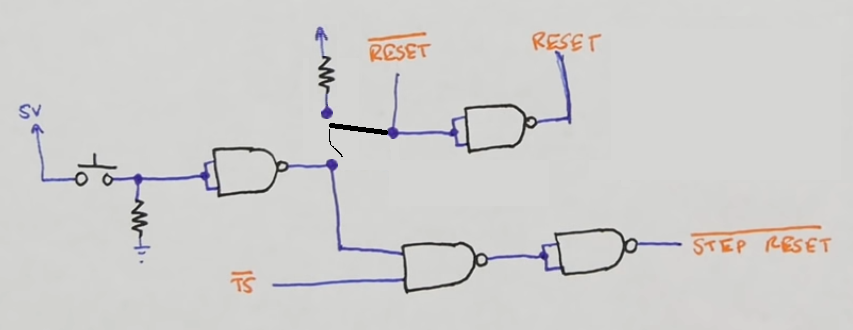

- Update after finishing the control unit:

- We will distinguish between the system clock and the microinstruction clock. The system clock is indeed needed to synchronize all components on the breadboards (i.e. registers), which means they all do their work only if the clock is high; never when it’s low. And because the clock speed is set above the longest time any signal needs to propagate through any circuit on the board, this system is preventing signals from arriving before other signals are ready and thus keeps everything safe and synchronized.

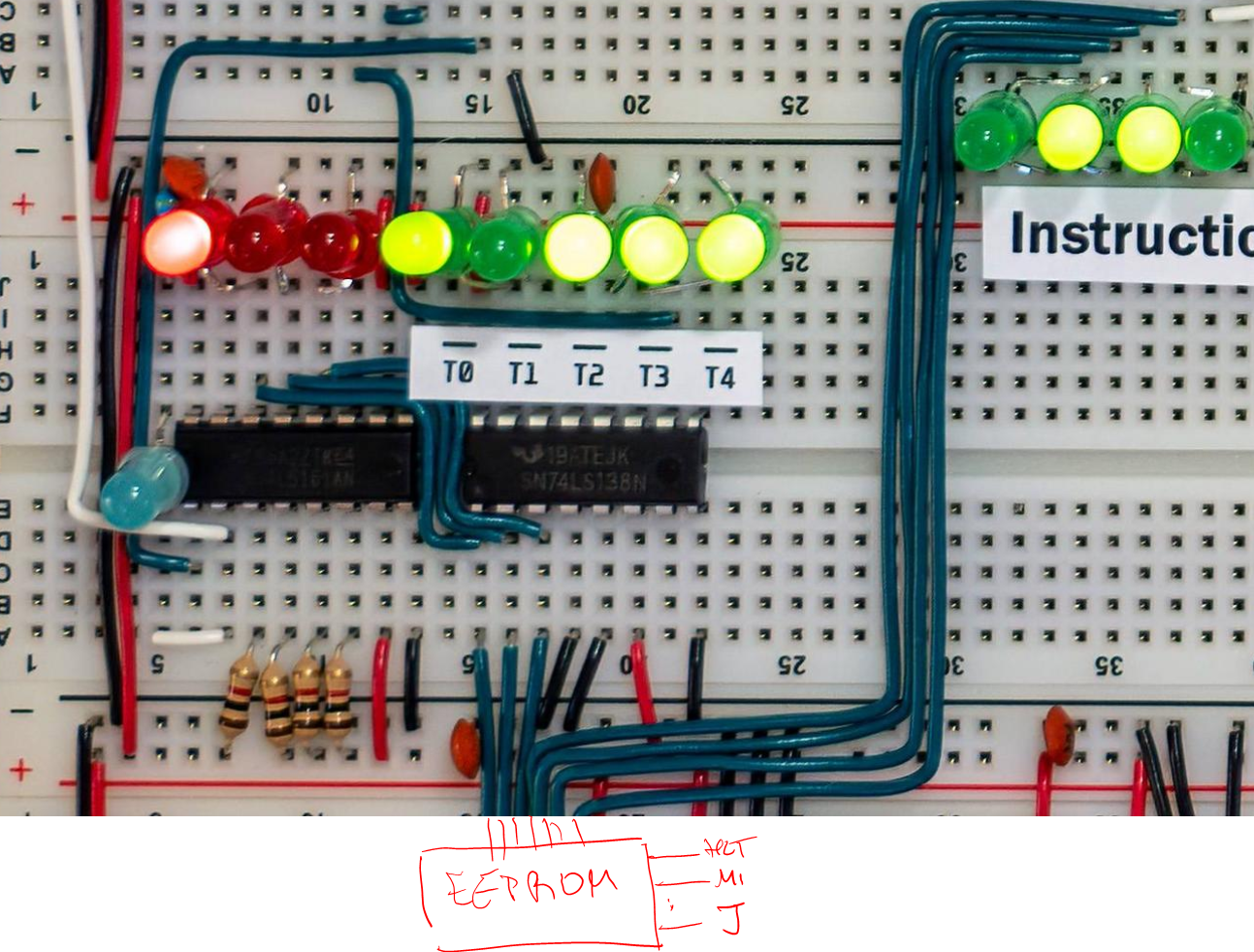

- These operation slots determined by high clocks are, at the lowest level, prepared by a counter that uses an inverted system clock signal that generates 3-bit time slots \(T_n\) for control circuitry such that control signals for the modules are ready before the next normal clock pulse.

- The operations at the lowest level are called microinstructions (as stated above, they are prepared at low clock pulse but executed at high clock pulse)

Astable 555 timer

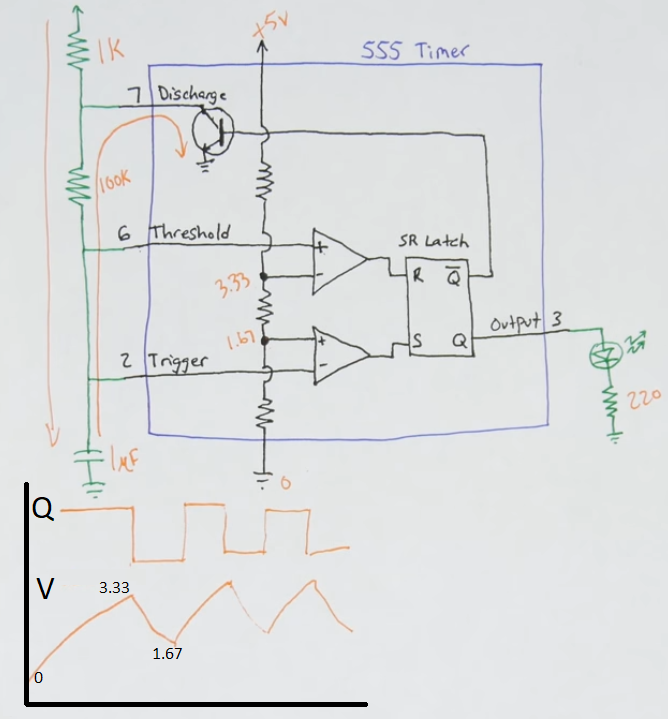

- We control the timing with 2 resistors and a capacitor

- The resistor connected from \(V_{cc}\) to pin 7 is of \(1k\Omega\)

- The resistor from pin 7 to pin 6 has \(100k\Omega\).

- The capacitor from pin 2 to ground is \(1\mu F\) (whose negative terminal is connected to ground)

- The breadboard rails are +5V and 0V (ground) although the voltage range of the 555 timer is typically 4.5 to 16 volts.

- The output of the 555 timer is around 3.3V and at least 2.75V

- The LED is connected to the output pin (3) and with a \(220\Omega\) as the current comming out of the output pin might burn it. The LED should alternate between on and off.

- It is called astable because it always alternates states

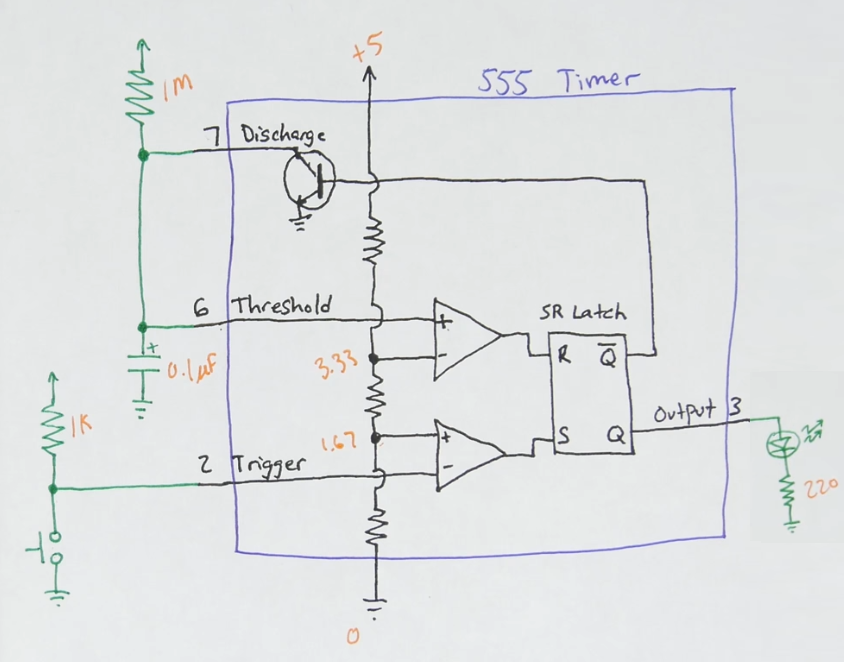

Schematic

- The opamps (triangles with +-) are in a comparator setting

- The comparator output signal specifies whether the voltage input (\(v_{in}\)) is above (\(v_{out}=1\)) or below (\(v_{out}=0\)) the reference voltage (\(v_{ref}\)).

- The 3 resistors inside the 555 timer are probably \(5k\Omega\) each and they form a voltage divider circuit

- Therefore with a 5V source the voltage drop of the bottom resistor is \(5V\cdot\frac{5k\Omega}{15\Omega}\approx 1.67V\) and the voltage drop of the 2 bottom resistors combined is \(5V\cdot\frac{10k\Omega}{15\Omega}\approx 3.33V\) (recall that all voltage values are given in relation to ground).

- Therefore the reference voltage of the top comparator is 2.33V and the input voltage of the bottom comparator is 1.67V

- Therefore with a 5V source the voltage drop of the bottom resistor is \(5V\cdot\frac{5k\Omega}{15\Omega}\approx 1.67V\) and the voltage drop of the 2 bottom resistors combined is \(5V\cdot\frac{10k\Omega}{15\Omega}\approx 3.33V\) (recall that all voltage values are given in relation to ground).

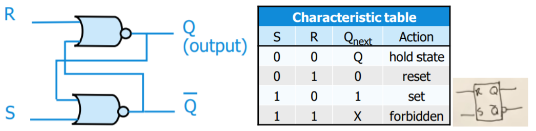

- You can also see that the output of the comparators feed the R and S terminals of an SR latch

Step response

- Assume the initial voltage of the capacitor is 0V and that the circuit has been powered off for a while

- The bottom comprator has \(v_{in} = 1.67V\) and \(v_{ref} = 0V\) as the capacitor had 0 energy stored. Since \(v_{in} \gt v_{ref} \implies v_{out} = High \implies S = 1\)

- The top comprator has \(v_{in} = 0V\) and \(v_{ref} = 3.33V\). Since \(v_{in} \lt v_{ref} \implies v_{out} = Low \implies R = 0\)

- From the truth table we see that S = 1 and R = 0 yield a high Q.

- \(\overline{Q}\) will be low and the transistor connected to pin 7 will not conduct.

- The capacitor starts increasing its voltage and at the beginning it’s low enough such that both comparators mantain the previous output but as soon as the capacitor reaches a voltage higher than 1.67 the bottom capacitor has \(v_{in} \lt v_{ref} \implies v_{out} = Low \implies S = 0\)

- While the capacitor has a voltage between 1.68 and 3.32 the top capacitor will keep \(v_{in} \lt v_{ref} \implies v_{out} = Low \implies R = 0\)

- SR = 00 means that Q which mantain whichever state it had, which in this is case was high and therefore \(\overline{Q}\) will be kept low and the transistor connected to pin 7 wont flow yet.

- As the capacitor surpases 3.34 the top comparator will have \(v_{in} \gt v_{ref} \implies v_{out} = High \implies R = 1\)

- SR = 01 means Q is low and \(\overline{Q}\) is high. The LED is now off.

- Since \(\overline{Q}\) is high the transistor will be connected to the branch emerging after the \(1k\Omega\) resistor, which since connects directly to ground it has zero resistance and all the current the previously flowed down pins 6, 2 and the capacitor won’t flow there as all of it will be discharged in pin 7

- Similarly the capacitor is also connected to the low resistance (although it has to go through a \(100k\Omega)\) resistor, recall that the inputs of an opamp have a very large resistance (not explicitly stated in the circuit), therefore the capacitor will also discharge via pin 7, and it’s voltage will start to drop.

- The top comparator will be the first one to switch from hight to low output, which would leave SR = 00, and mantain the current status quo.

- As the voltage of the capacitor drops below 1.66 volts the bottom comprator will switch from low to high output, which leaves SR = 10, which sets Q high (LED is back on) and \(\overline{Q}\) is low, which disconnects the discharger and everything is set back to the starting point (except that the capacitor might not have been fully discharged before it starts charging againg)

- While the capacitor has a voltage between 1.68 and 3.32 the top capacitor will keep \(v_{in} \lt v_{ref} \implies v_{out} = Low \implies R = 0\)

Speed

- The flashing frequency of the led is determined by Q which is determined by how quickly the capcitor charges and discharges

- This is determined by how much current flows into the capacitor

- The more resistance in the resistors, the less current flowing into the capacitor and the slower it’s going to charge (and also the slower it’s going to discharge as fewer current will be travelling back to the discharger)

- The larger the capacitance the longer it takes to charge/discharge. From here it follows that the bigger R * C the slower the clock

- The reason Ben has chosen 1k and 100k resistors is because charging will go through 101k resistance and discharging through 100k resistance making the high and low Q values of almost identical time.

- The charge time (Q output high) of the 555 timer given by its data sheet is: \(t_1=0.693(R_a + R_b)C\) with \(R_a\) being our 1k resistor and \(R_b\) the 100k one.

- Discharge time (Q output low): \(t_2 = 0.693 \cdot R_b \cdot C\)

- The total period is \(T = t_1 + t_2 = 0.693(R_a + 2R_b) C\) which in our case is 0.139 s

- The frequency (of oscillation) is \(\frac{1}{T}=\frac{1}{0.139}=7.19\) which means that the LED is flashing about 7 times per second

- We can replace the 100k resistor with a 1k resistor and a potentiometer in series (so when the potentiometer has 0 resistance there’s at least a 1k ressitor between pin 6 and 7) to manually adjust the speed of the clock

Noise

- Adding a \(.01\mu F\) capacitor from ground to pin 5 is recommended by the 555 timer datasheet as it clears the noise from low to high

- Our power supply (typically with curled wires) may act “not perfect” (i.e. as an inductor sometimes) and sometimes components (specially transistors) might get more volts than they actually desire at times.

- Adding a \(.1\mu F\) capacitor parallel to the power supply (i.e each leg on a + and - hole respectively in the breadboard) may help reduce dangerous voltage jumps.

- Ideally you’d want to have this capacitor right next to the power pins of the chip but there aint that much space in a breadboard.

- Low voltage on pin number 4 triggers a SR = 01 that overwrites whatever is going on with the comparators and resets (turns off) the SR latch. Therefore the datasheet recomends to hookup pin 4 directly to 5V power supply

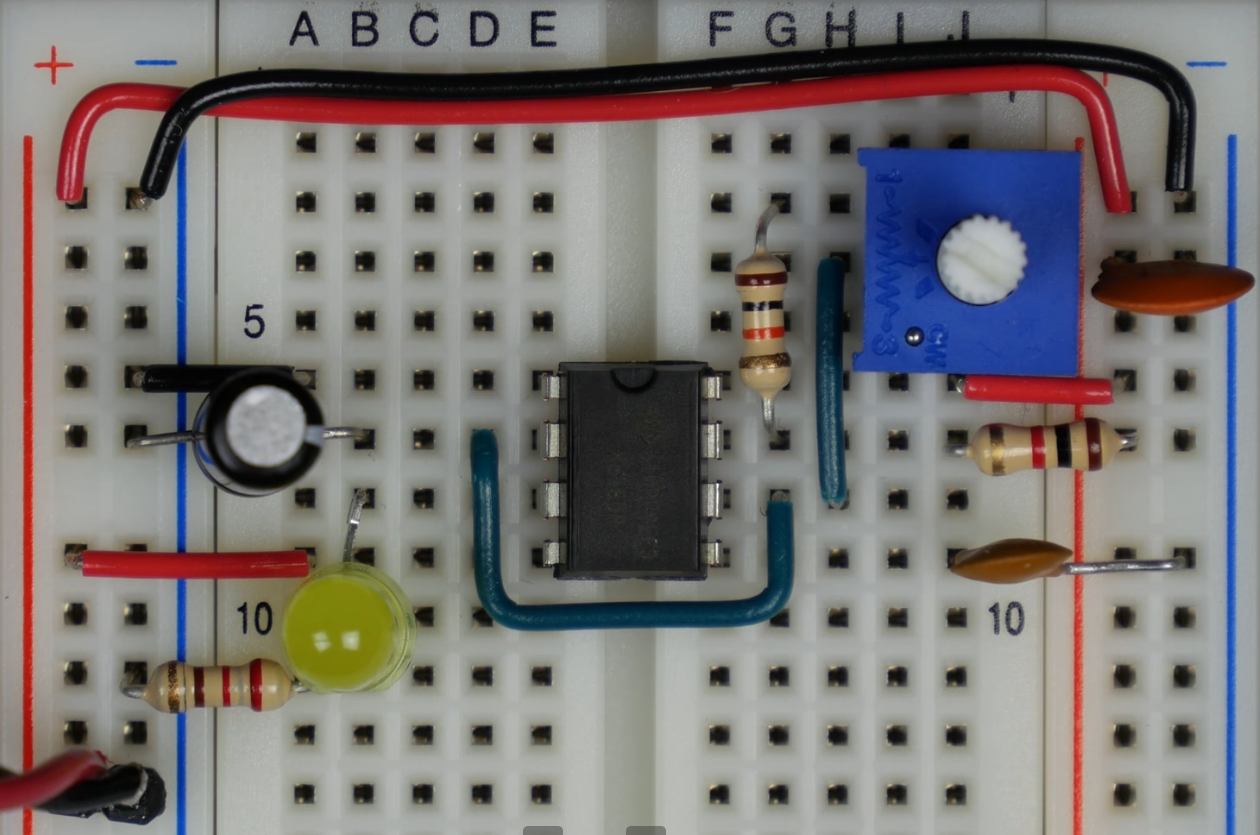

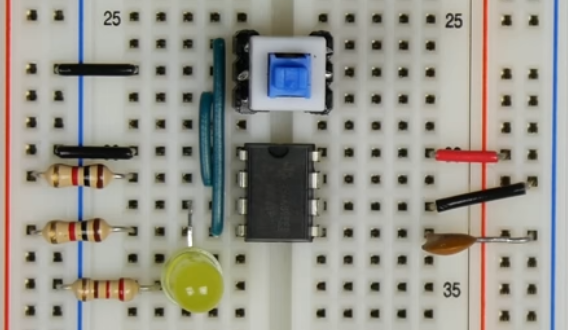

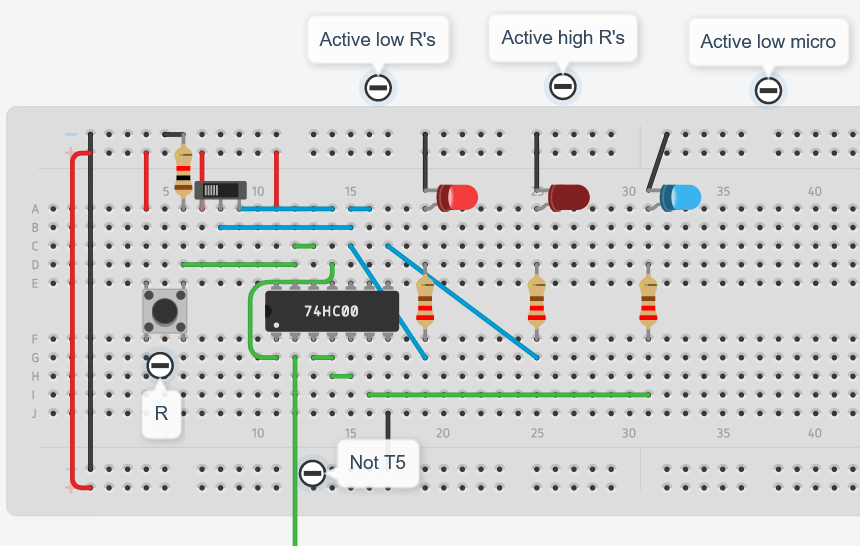

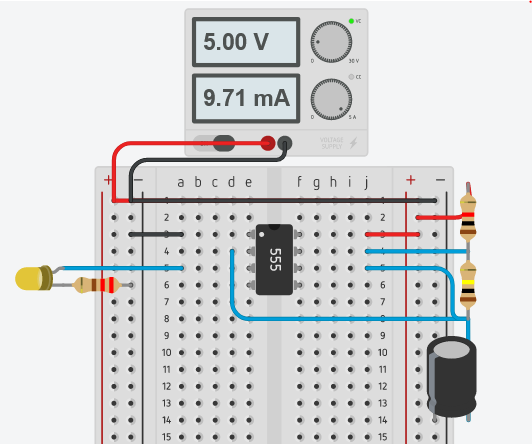

When we add all the noise and manual speed adjustments we end up with the following breadboard:

Tinkercad

-

Tinkercad of the original schematic

Open tinkercad

Open tinkercad - Tinkercad of the upgraded circuit

- \(1M\Omega\) Potentiometer in series with Resistor B, which it decreases from \(100k\Omega\) to \(1k\Omega\) to manually adjust the speed.

- \(.1\mu F\) capacitor parallel to power supply to control voltage spike noise

- \(.01\mu F\) capacitor from ground to pin 5 to control low to high clock signal noise

- \(V_{cc}\) to pin 4 to avoid unvoluntary clock resets

Open tinkercad

- Ben replica

- (Not inteded to implement in real life) Replaced the polarized capacitor with a small capacitor as it takes less space on the breadboard (it still has \(1\mu F\)).

- Shifted (aesthitically only) components to take less space.

- Placed everything on the breadboard

Open tinkercad

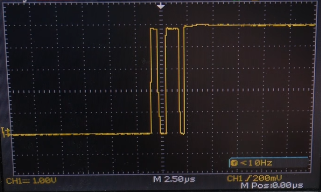

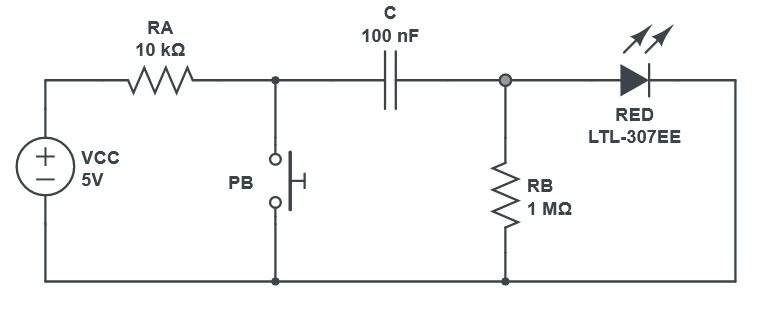

Monostable 555 timer

- We want to be able to manually advance 1 clock cycle

- Although a simple pushbutton seems to be enough to create cycles

- In reality the push button mechanics might unvoluntarily create additional clock cycles as the metal bounces additional times, not susceptible to the human eye

- In reality the push button mechanics might unvoluntarily create additional clock cycles as the metal bounces additional times, not susceptible to the human eye

- A debouncing circuit deals with this issue

- The duration of the high signal is determined by the capacitance times resitance of the two components on the right.

- It is called monostable because it only has 1 stable status (low)

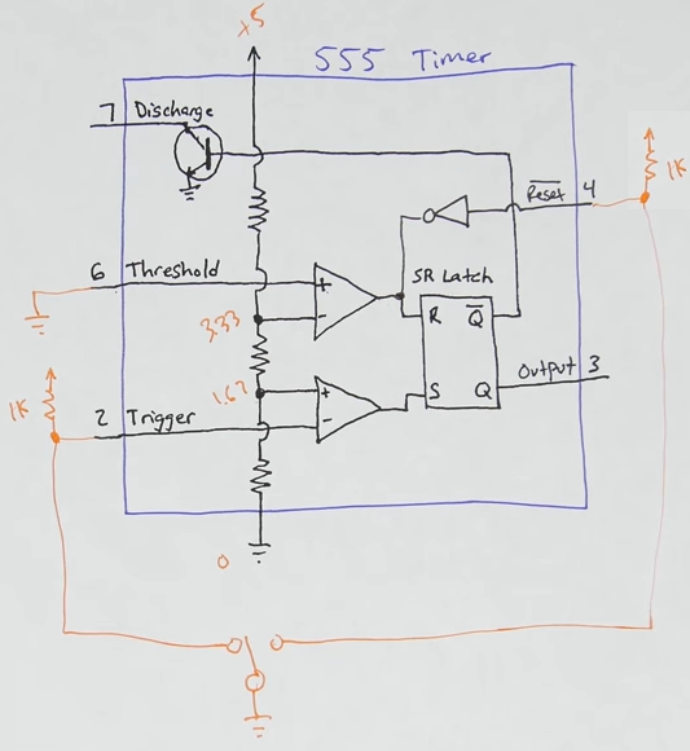

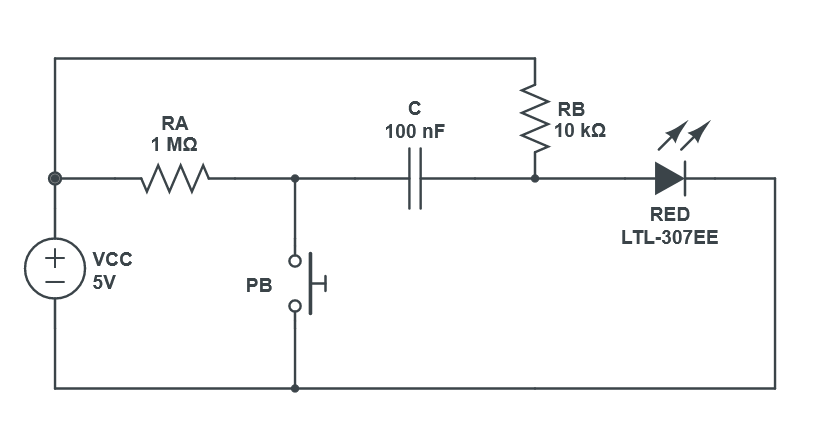

Schematic

- Like the previous 555 timer circuit, there’s a resistor connected to pin 7 (discharge), but here it is also directly connected to pin 6 (threshold) as there is no resitor “b”.

- The capacitor (which determines the duration of the signal together with resistor a (the \(1M\Omega\) one), is also connected directly to pin 6 and 7

- The output lights a LED in series with a \(220\Omega\) resistor.

- Pin 2 is connected to a node that has a \(1k\Omega\) resistor directly connected to \(V_{cc}\) on the positive terminal and a push button directly connected to ground on the negative terminal

- I’ts like a voltage divider with \(R_1\) being 1k resistor and \(R_2\) the switch.

- \(v_0=v_s\frac{R_2}{R_1+R_2}\)

- When \(R_2\) is an open circuit it has infinity resistance, which gives \(v_0=v_s\frac{\frac{R_2}{R_2}}{\frac{R_1}{R_2}+\frac{R_2}{R_2}}=v_s\frac{1}{\frac{1}{\infty}+1}=v_s\)

- When \(R_2\) is a short circuit then \(v_0=v_s\frac{0}{R_1+0}=0\)

- When the push button is open, the voltage of pin 2 is \(v_{cc}\)

- The bottom comparator sends output 0 = S (which either resets or leaves current state)

- When the push button is closed, the voltage of pin 2 is 0

- The bottom comparator sends output 1 = S (which then sets the SR latch and triggers a high output

- I’ts like a voltage divider with \(R_1\) being 1k resistor and \(R_2\) the switch.

Step response

- Initally the push button is open so the bottom comparator sets S = 0, the LED is off and so is \(\overline{Q}\) high, which enables the discharge transistor. The capacitor which has 0V, is not able to charge, therefore the top comparator will mantain R = 0. The current state is kept (led off) until we intervene

- Only after pushing (and release) the button we can triger SR = 10 as we made the voltage of pin 2 to be 0 and hence the bottom comparator is able to set S = 1, which makes Q high and \(\overline{Q}\) low.

- This disables the discharge transistor and allows the capacitor to increase its voltage, the capacitor increases its voltage and when it’s above 3.34V it will reset the clock (given that the pusshbutton is not held on, otherwise we encounter SR = 11 which in an SR latch is an illegal configuration (it gives unpredictable output))

- As long as we dont deliberately hold the push button for too long this implementation should deal with the noise from the push button bounces

- After the capacitor triggers the reset, \(\overline{Q}\) becomes high and enables the discharge again, since there is no resistor between discharge and the capacitor it will bleed out it’s voltage very quickly, which immideately sets R back to 0.

- Therefore it’s very unlikely to achieve SR = 11 by doing very fast clicks (or rebounds), it should only possible by deliberately holding the button

- Therefore it’s very unlikely to achieve SR = 11 by doing very fast clicks (or rebounds), it should only possible by deliberately holding the button

Noise

Datasheet recomends:

- \(.01\mu F\) capacitor from ground to pin 5

- 5V to pin 4

Tinkercad

-

Tinkercad of the original schematic

Open tinkercad

-

Ben replica (with noise upgrade)

Open tinkercad

Bistable 555 timer

- We could use a switch to manually alternate between the high and low clock output states

- However if we just use a mechanical switch we face the same rebound issue

- Since the 555 timer has a built-in SR latch, we can we can use it to set/reset the clock style as it also acts as a debouncer (because it latches the last state).

- We use a switch that is “break before make”

- The bouncing is always between the next step and the break, so any bouncing is not harmful as the desired result has been already latched as we’ll show below

- We use a switch that is “break before make”

- It is called bistable because both high and low output states are latched

Schematic

- We connect the threshold pin to the ground and just use the trigger pin (2) to set S = 1 (via the bottom comparator) and the reset pin (4) to directly (skipping the top comparator) set R = 1

- Since threshold is always below 3.33, R will always be 0 except when deliberately using the reset pin.

- Basically we need to send a low signal either to pin 2 (because it is inverted) xor pin 4 (because we want the trigger input of the comparator to be lower than 1.67) to set and reset respectively.

- Since we have a break-before-make switch, we will either:

- Connect pin 2 to ground (and make it 0V instead of the previous \(V_{cc}\)), which sets S = 1

- Break (neither pin 2 nor 4 are connected to ground): hold state

- Pin 2 has \(V_{cc}\) and therefore S = 0

- Reset pin is an open circuit and therefore doesn’t overwrite the top comparator, who always outputs low, so R = 0

- Connect pin 4 to ground and set R = 1

- The \(1k\Omega\) resistor on pin 4 is to connect 5V to pin 4 as recommended by the 555 datasheet and we use a resistor instead of just a piece of wire as pin 4 is also connected to ground and we do not want a short circuit.

- Not included in the schematic is the \(.01\mu F\) capacitor from ground to pin 5

Tinkercad

-

Tinkercad of the original schematic

Open tinkercad

-

Ben replica

Open tinkercad

- Sometimes the switch icon might have an off starting image but tinkercad starts by default in the on position, so if things don’t seem to match at first glance just click once and the switch image will match the switch value

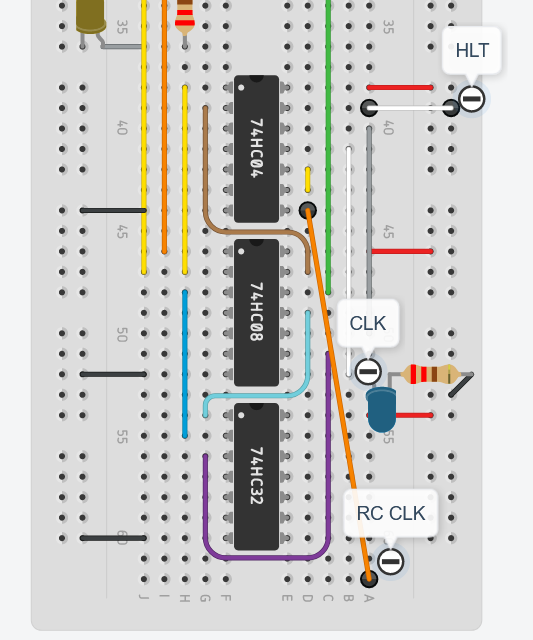

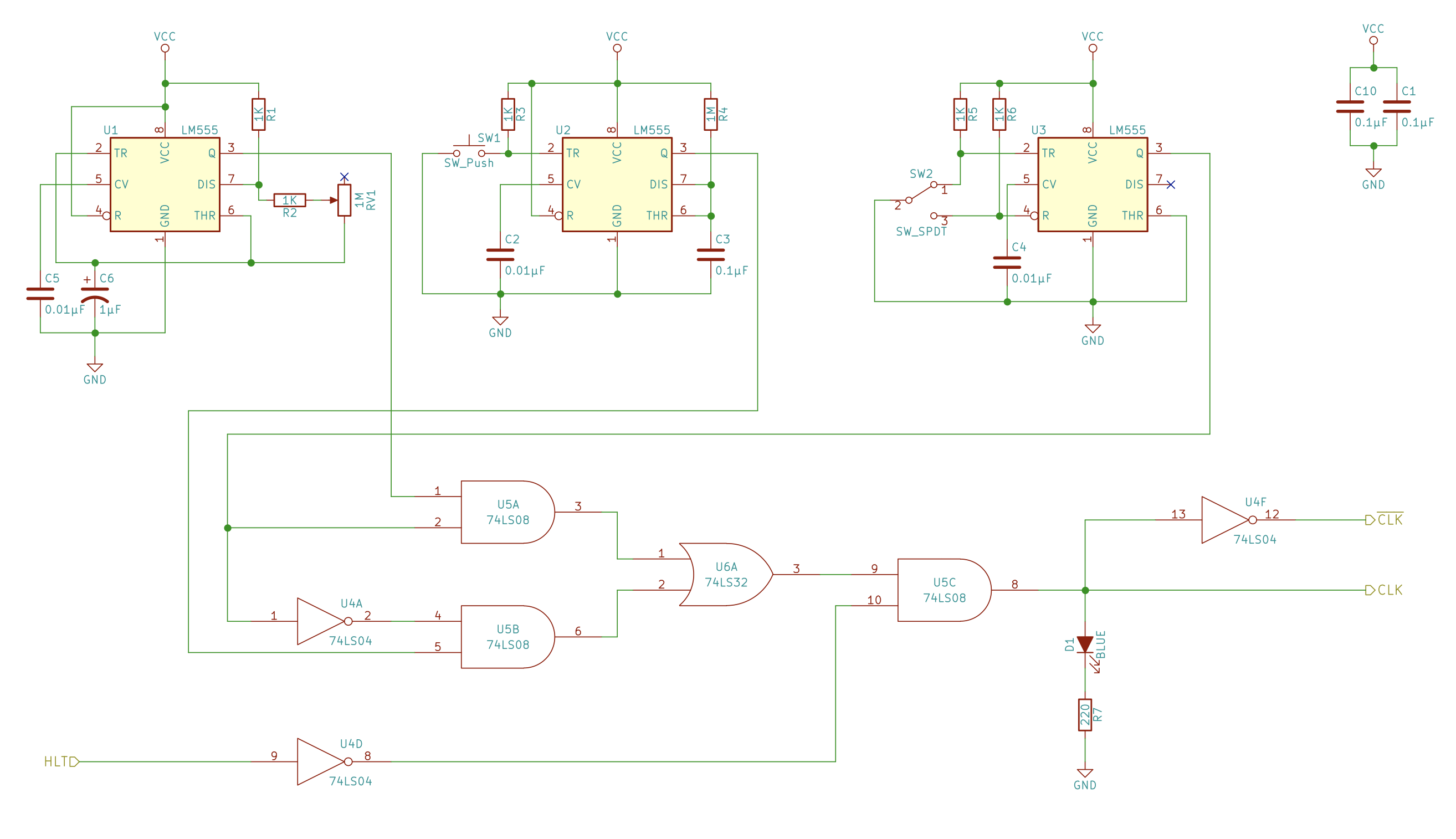

Clock logic

- We want to have one single clock output terminal that can be configured to either be a copy of the astable (automatic) or monostoable (manual) clock signal.

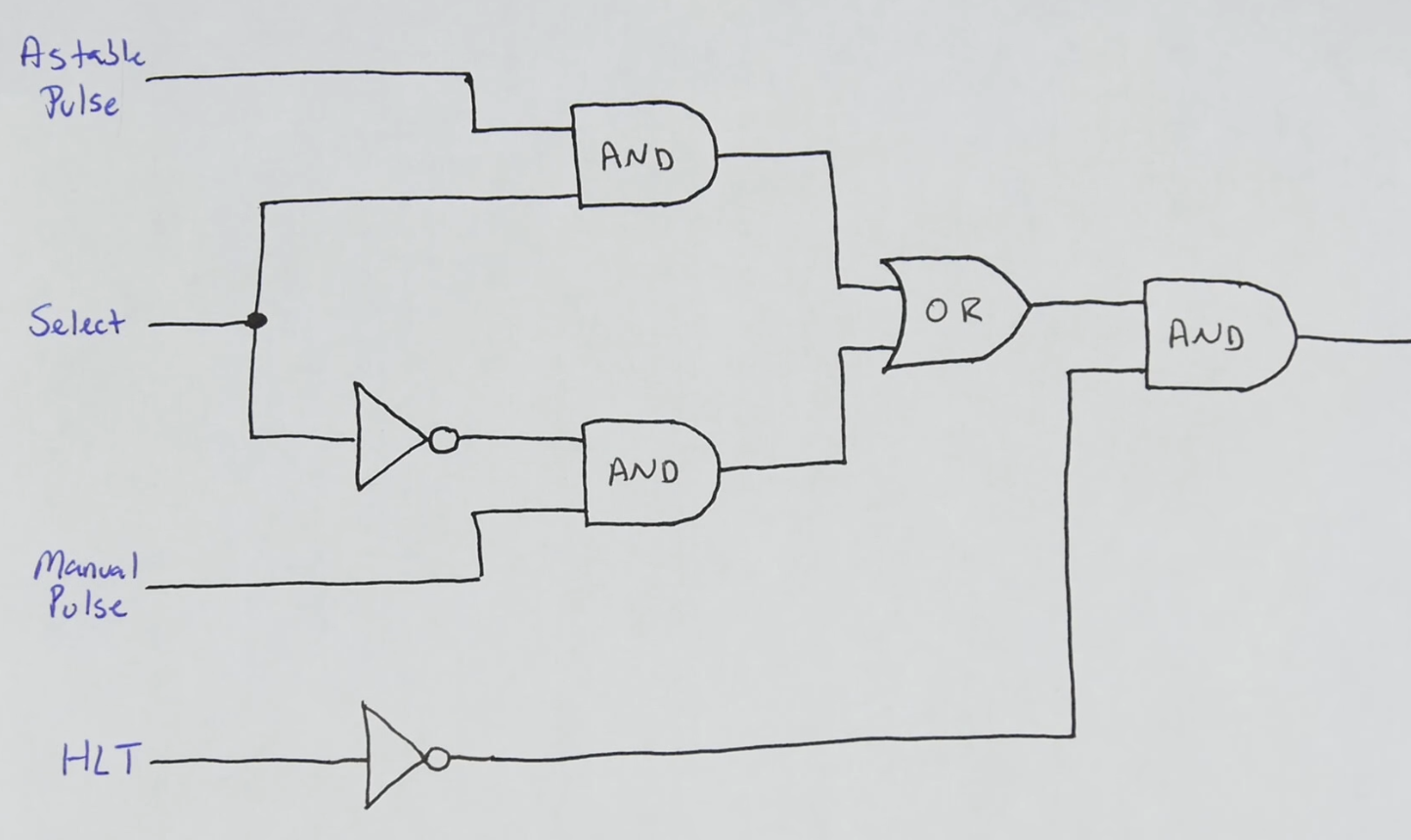

Logic circuit

- HLT stands for halt signal (which can be send by programs) to stop the clock

- Latches low clock signal when we send a high voltage in HLT

- Low voltage does not interfere with the regular clock logic (described below)

- The logic circuit uses the bistable (called “select” in the schematic) clock just as a debounced switch, so the circuit is just to alternate between using the monostable clock (manual) and the astable clock (automatic)

- Because of the inverter of the select signal, exclusively and always one of the AND gates feeding from the clock signals will output a high voltage

- Take away:

- High bistable switch = astable

- High bistable and monosstable push = astable signal (the push is ignored)

- Low bistable switch = monostable

- high HLT (halt) = low clock signal until unhalted (then back to the previous clock setting)

- High bistable switch = astable

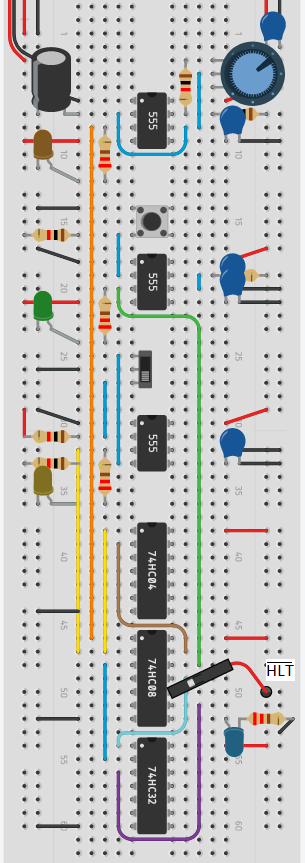

Components

- 1 74LS04 hex inverter

- Contains 6 inverters (we need 2)

- 1 74LS08 quad AND gate

- Contains 4 and gates (we need 3)

- 1 74LS32 quad OR gate

- Contains 4 or gates (we need 1)

- It would have been more efficient to rewrite the circuit with NAND gates and just use 2 74LS00 NAND chips (to use 7 out of 8 nand gates) but we’re not trying to optimize for power nor space but for understanding and maintanence.

- Tinkercad uses 74HC chips, which are slightly different than the 74LS chips shipped by Ben:

- 74LS need 5V \(V_{cc}\) and output a high voltage of 3.4V and a low voltage of 0.2V

- 74HC accepts from 2V to 6V and outputs with an output between 0 and \(V_{cc}\)

- Both have the same pin outs and most 74LS logic chips have internal resistors that let you connect LEDS directly to the outputs without a resistor. However, 74HC generally not.

- Therefore the tinkercad implementations have a \(220\Omega\) resistor in series with output LEDs.

Tinkercad

-

Tinkercad of the logic circuit without the HLT inverter and last AND gate.

Open tinkercad

- Tinkercad with the HLT inverter and last AND gate.

- Just plugs the output of the OR gate into an AND gate that for now takes the other input from a jumper cable either to ground (halt) or \(V_{cc}\) (not halt).

Open tinkercad

- Just plugs the output of the OR gate into an AND gate that for now takes the other input from a jumper cable either to ground (halt) or \(V_{cc}\) (not halt).

- Simplified aesthetic circuit(with 74HC and \(220\Omega\) resistors) has the same logic connections:

- (Astable out, AND gate In 1A) - orange

- (Bistable out, AND gate IN 1B) - yellow

- (Bistable out (or AND gate in 1B), Inverter gate In 1) - yellow

- (Inverter gate Out 1, AND gate In 4B) - brown

- (Monostable out, AND gate In 4A) - green

- (AND gate out 1, OR gate In 1B) - dark blue

- (AND gate out 4, OR gate In 1A) - light blue

- (OR gate out 1, AND gate in 3A) - purple

Schematic

- Note: I ended up inverting the halt input as suggested by the schematic here

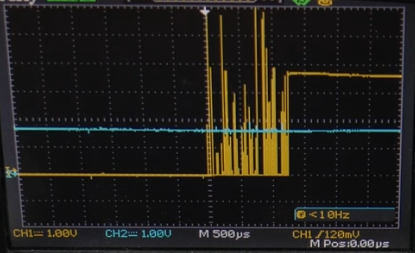

Testing the clock

- The clock can be fully tested in tinkercad by starting a simulation

- In real life the only adjustment I might need is to fix double bouncing of the push button, which happens occasionally.

- However it doesnt seem to be a capacitor resistor/555 timer issue as I can clearly notice the double clock pulse with the naked eye. It seems to be a mechanical issue, maybe I should replace the \(1k\Omega\) capacitor for a 10k one if the issue bothers me too much.

Registers

- Components included in the kit (including the components for ALU)

- 4 Breadboards

- 1 Jumper wire kit

- 6 25 foot hookup wire spools

- white

- blue

- green

- red

- yellow

- black

- 2 74LS86 quad XOR gate

- 6 74LS173 4-bit D register

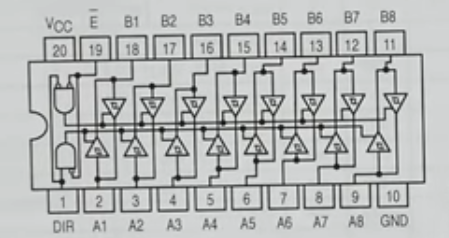

- 4 74LS245 8-bit bus transceiver

- 2 74LS83 4-bit binary adder

- 40 \(220\Omega\) resistors

- 30 Red LEDs

- 10 Yellow LEDs

- 5 Blue LEDs

- 10 \(0.1\mu F\) capacitors

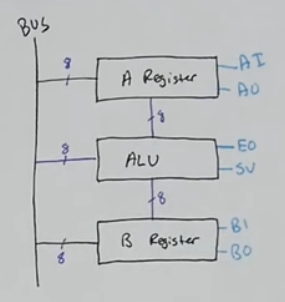

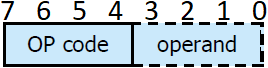

- Most CPUs (central processing unit) have a number of registers which store small amounts of data that the CPU is processing. In our breadboard CPU, we’ll build three 8-bit registers: A, B, and IR (instruction register)

- A and B are general-purpose registers

- IR will be used for storing the current instruction that’s being executed.

- The arithmetic logic unit (ALU) part of a CPU is usually capable of performing various arithmetic, bitwise, and comparision operations on binary numbers.

- Our ALU is just able to add amd substract

- It’s connected to the A and B registers

- Outputs either A+B or A-B

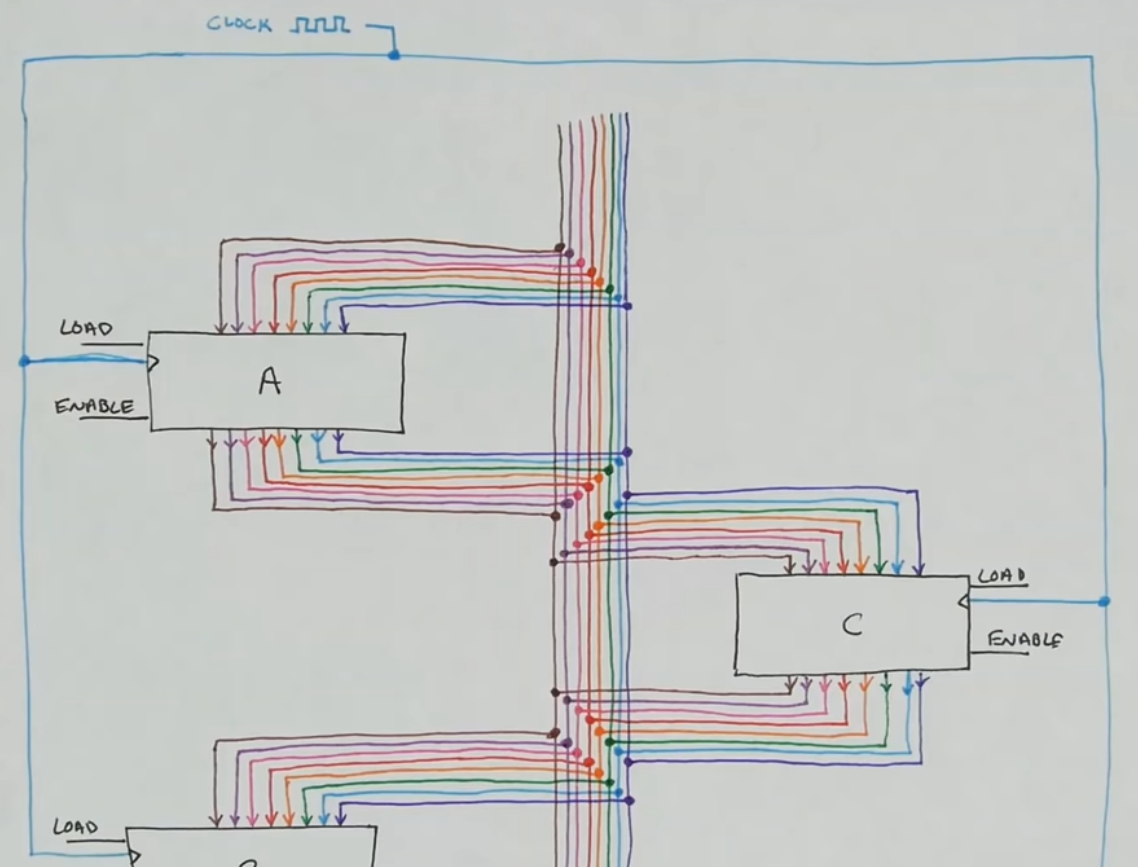

Bus architecture and how registers transfers work

- Our registers store 8 bits of data and interfaces (as in “provides interaction features”) to the Bus

- Most computers are organized around a Bus (or multiple)

- The Bus is basically a network of cables that connect multiple components within a computer.

- It’s a rather simple network, as the Bus serves primarly as a common connection point for multiple components within the computer

- For the 8 bit Bus we use 8 wires, and 4 snapped (+ -) power rails from 2 breadboards

- The way we use the bus is by one module writting data onto the Bus and another module reading data from the Bus

- Only 1 module can write data on the Bus at a time, otherwise the data carried on the bus is corrupted

- One of the main things a register does next to storing data is loading data onto the bus so other components can read it from the bus

- Registers have pins that when triggered with high/low voltage they can either read data from the bus or write it onto the bus.

- When “Enable” is high, the current data stored in the register is written (and overwrites) onto the bus. Then it’s visible to all the other modules (but they dont necessarily need to do anything with it)

- When “Load” is high, the register overwrites it’s current value with whatever value appears on the bus.

- Registers have pins that when triggered with high/low voltage they can either read data from the bus or write it onto the bus.

- The timing of each Load/Enable operation with the bus is synchronised by the clock signals as Load/Enable is gated with AND clock.

- Everything connected to the bus can potentially talk between all of them.

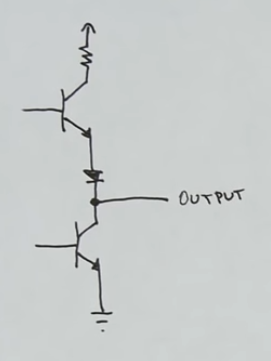

Connecting multiple outputs together

- The “Enable” output gates have some sort of transistor network that manages to either have an output that emits current from the pullup network (\(v_{cc}\) or an output that sinks current to the pull-down network (ground).

- The transistors above are NMOS (incomming high voltage closes the circuit)

- If top is high and bottom is low the output sources current

- If top is low and bottom is high the output sinsk current

- The load pins detect the current of the input pins connected to the Bus (which are connected to the register/component that is enabling its output pins) to determine whether the pin is a 0 (sinks) or a 1 (emits)

- This works well when only 1 component is emmiting/sinking current from the bus

- If component A emits all 1’s but component B is sinking all 0’s then component C will read a corrupted version of A’s data.

- Instead, the pull-up/pull-down transistor network for the outputs rather than having always closed circuit (either to ground or to \(v_{cc}\)), we can have a tri-state logic where we can just disconnect the output and leave an open circuit such that the outputs do not interfere with the Bus (unless enable is turned on, which shall be enabled by at most 1 component)

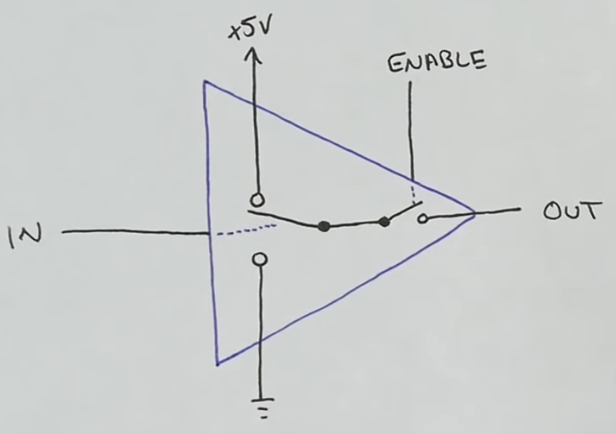

Tri-state logic

- If IN = 1, then switch is connected to \(V_{cc}\)

- If IN = 0, then switch is connected to ground

- If and only if enable is on, the output (a copy of IN) is connected to the bus

- So we end up with:

- Out = 0

- Out = 1

- Out = disconnected (does not overwrite the Bus)

- It is technically “high impedence” (with high resistance) as mechanically opening the circuit takes much more time and energy

- The input and output pins of the 74LS245 bus transceiver are connected to the enable pin a similar fashion

- We generally hide the pullup and pulldown network in the tri-state gate symbol

Designing and building a register

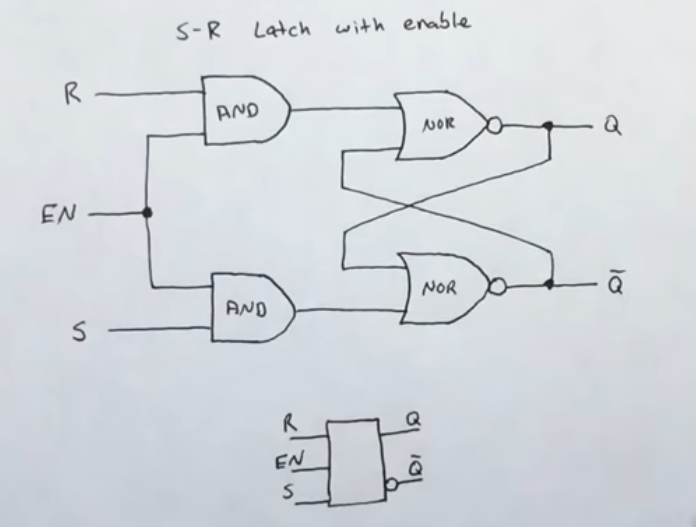

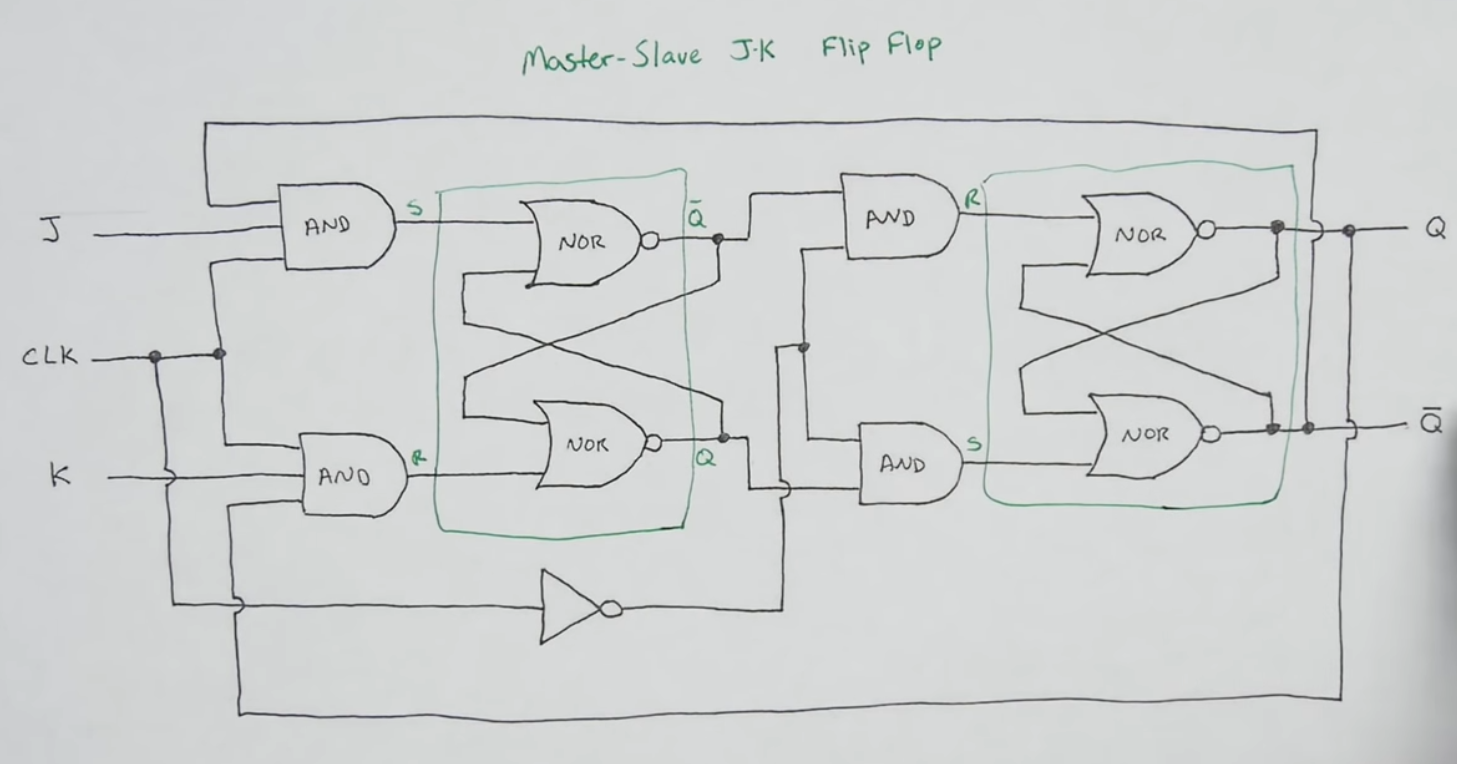

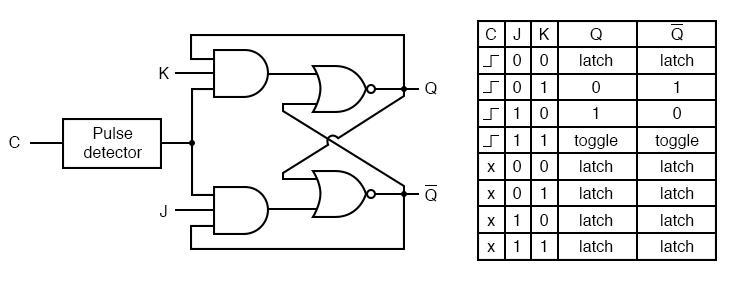

SR latch (store 1 bit)

- We can use an S-R latch with an enable button that specifies when SR can be fed into the SR latch

- When EN is 0, both AND gated output SR = 0, so the SR latch holds the previous state

- When EN is 1, the SR latch will get whichever values for S and R exist.

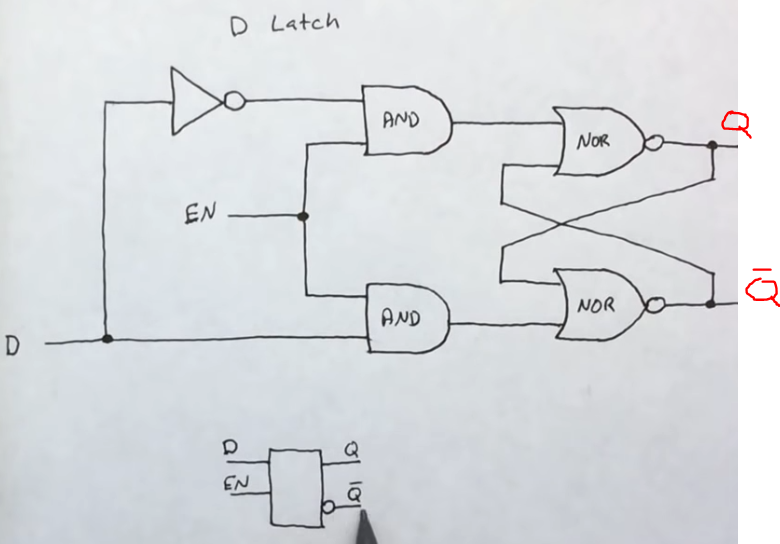

- We can create one single variable called D that feeds S and another branch of the same variable can be inverted and feed R. Therefore if D is 0 we get SR = 01, and if D is 1 we get SR = 10

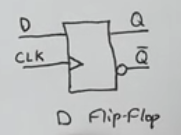

D latch (just use 1 input)

- This is called a D-latch because it latches a single bit of data

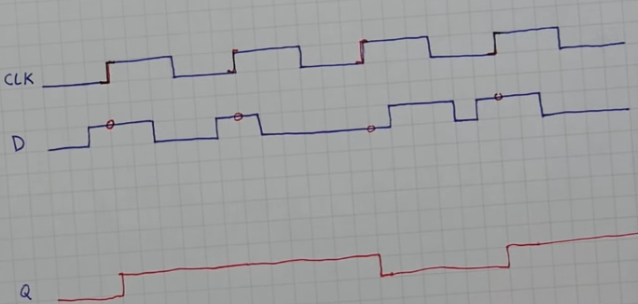

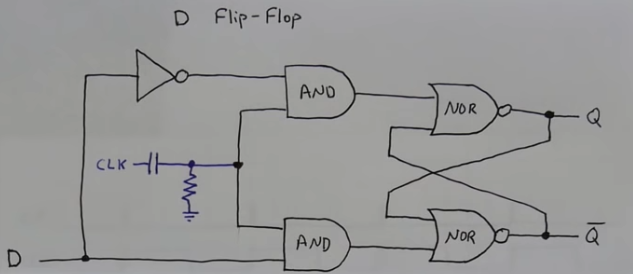

D flip flop (latch at clock pulse)

- A D-flip flop would only latch a D value specifically when Enable is ON and when the clock switches from low voltage to high voltage (this prevents any other D changes during the same high clock signal cycle)

- This is technically enabling at each clock pulse

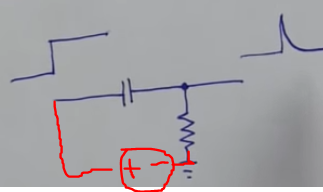

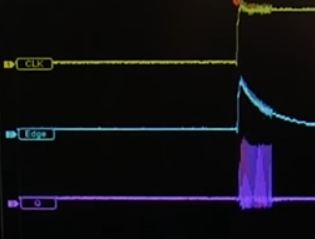

- We need an (edge detector) resistor capacitor (RC) circuit to produce a signal with very short high cycles (pulses)

- The circuit above is such a circuit, which basically has a voltage as high as the source and behaves as the step response of a conductor-resistor circuit.

- Although at \(t_0\) (step from 0 to high voltage) the capacitor has 0V and behaves like a wire (\(I_s\) current), the voltage we are interested about is of the node connecting to the positive terminal of the resistor, which at \(t_0\) looks like \(R_2\) from a voltage divider where the inductor looks like \(R_1\) with \(0\Omega\) resistance, and thus \(V_0=V_s\) (high)

- The smaller the capacitance of the capacitor, the less it takes for the capacitor to charge, (and decrease it’s current), and thus the sooner the voltage drop of the capacitor reaches \(V_{s}\) and since it’s in series with the source the sooner it decreases the available voltage for all branches connected to \(V_{s}\) (KVL)

- According to to the RC constant:

- T = RC

- At 1T the voltage drop of fully charged capacitor in a natural response circuit is -37% (it’s providing voltage) of the initial voltage of the capacitor. The voltage drop of an empty capacitor in a step response circuit is therefore 63% of the source voltage (the resistor gets 37%)

- These are already considered significant enough to change a signal from logic high to logic low and viceversa

- After 5t the voltage drop is -1% of the initial source value in a natural response circuit (almost has no voltage to provide). In a step response circuit 5t makes the capacitor drop 99% of the source voltage (the resistor gets 1%)

- In a step response circuit the available voltage to the input pin will be the same as the one for the pull-down resistor, which will be \(V_{clock}\) minus the voltage drop of the capacitor. Overtime (5t) we see that the circuit is monostable until the clock signal is low again, but then the capacitor should discharge via the resistor (but when this happens it should not trigger a logic high because the voltage is not large enough for the chip to be considered high)

- AND gate output voltage (clock signal voltage) is typically 3.4V

- At 1T capacitor drops 63% of the voltage, which makes it \(3.4V \cdot .63 = 2.04V\). The mux high level input voltage is 2V, so 1T is a good approximation for the time it takes to switch from high to low, but it’s slightly more than 1T as we could see.

- At 5T capacitor has 99% of the 3.4V, which when discharged should give another high signal. This explains the double clock pulse that other components experienced when this RC circuit shared the same clock signal, but then we used a diode for the branch of this RC circuit. It may be the case that in practice the RAM is doing double clock pulses, but it does not affect the functionality of the computer.

- \(0.1\mu F\cdot 1k\Omega\ = 0.1\cdot 10^6 F \cdot 10^3 \Omega = 0.1 ms\)

- According to to the RC constant:

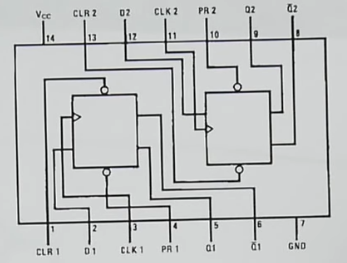

74LS74 (Two D flip-flops) and a load signal

- We can put several D flip flops together with some additional logic that write the contents of the bus when “Load” is high

- We can see that via the inverterter and the 2 AND gates linked to the load signal, the D bit fed to the D-latch is either the one of the bus when load is high, or the one latched when the load is low

- We can use 4 74LS74 chip which have 2 d-flip flops each built into it to make an 8-bit register

- GND: ground

- \(V_{cc}\): positive supply terminal

- CLRn: overwrites Bit n to 0

- PRn: overwrites Bit n to 1

- Flip flop pins: Dn (bus’ n bit), CLKn, Qn, \(\overline{Qn}\)

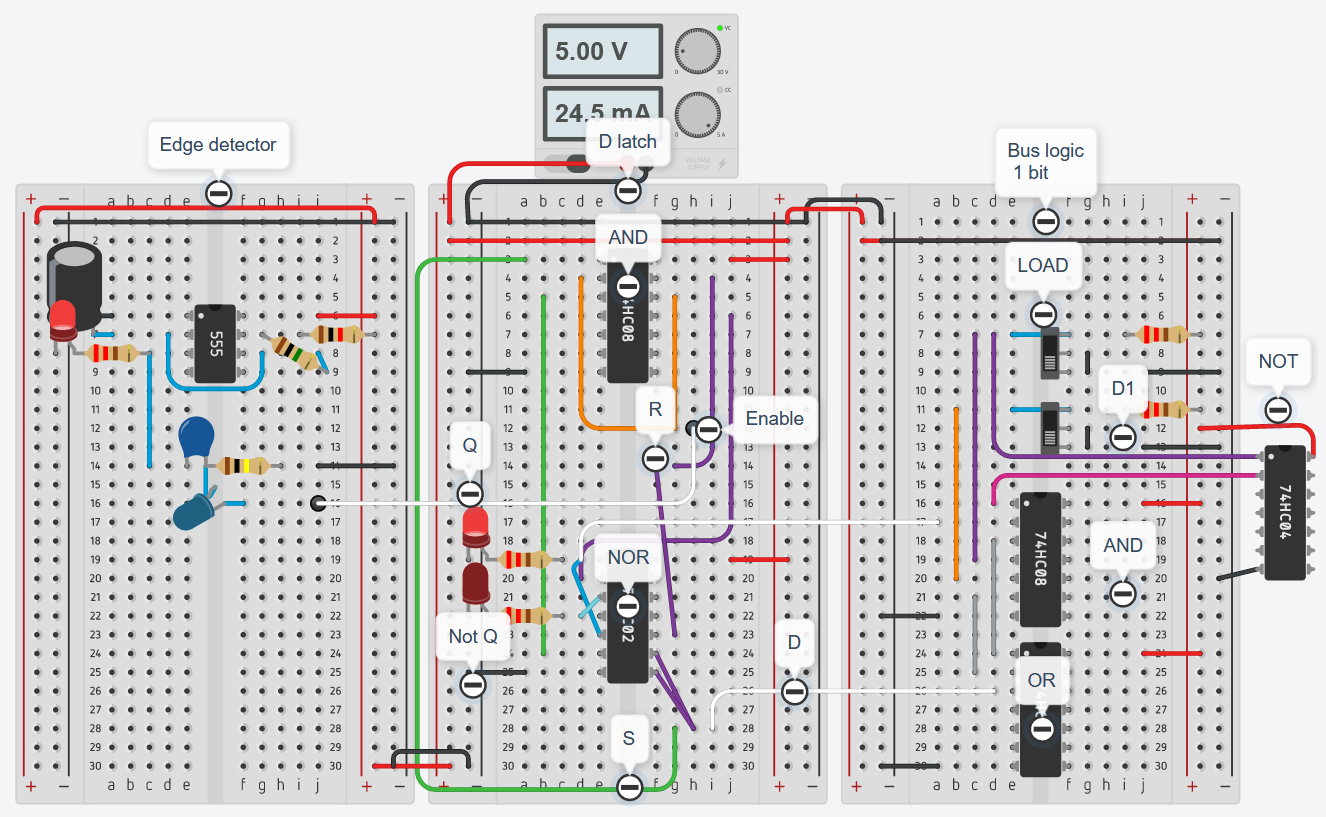

- Tinkercad implementation of 1 bit register

- It only allows register changes at clock rise (blue led on) and when load is high

-

We still need to add the tri-state buffer to the output of the register to ensure we dont corrupt the bus when we’re not using it

- Alternatively we can use the 74LS245.

74LS245 (Octal bus transceiver used as tri-state logic gate)

- Useful for sending bus data in both directions

- Pin 1 is for direction control (whether the register sends data or whether the bus sends data)

- Because we already use the load variable to determine when to read from the bus we just need to use the feature to send (An pin to Bn pin), so we set pin 1 high.

- Pin 19 is “enable”, which is the tri-state logic “switch” that connects/disconnects us from the bus

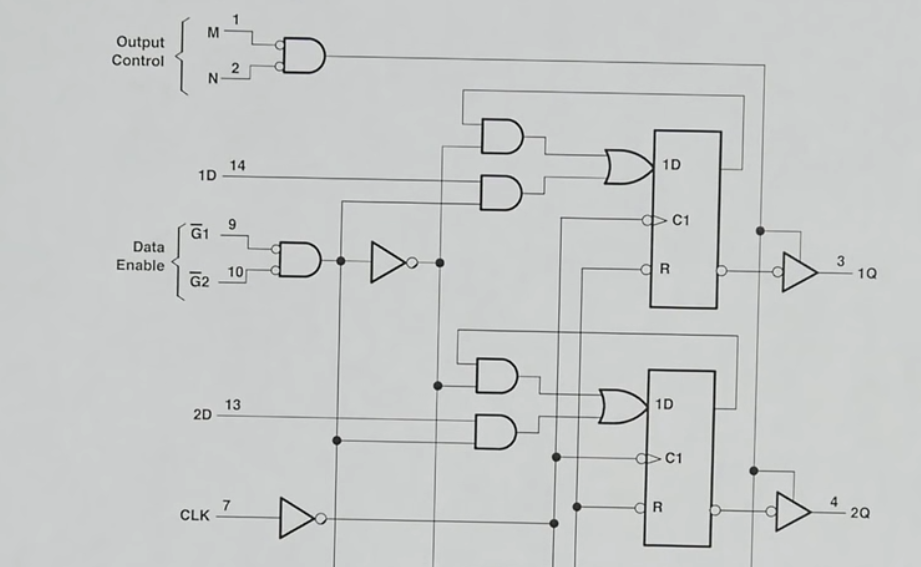

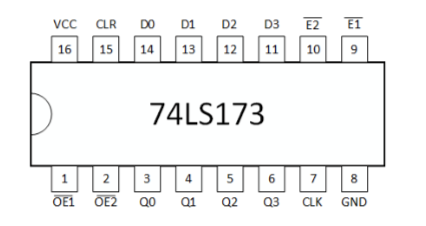

74LS173A (4 bit registers)

- 4 built-in D flip flops

- Uses similar logic of having a sequence of flip-flops connected to the bus and written when a load signal (called enable) is high

- Built-in tri-state output with output control pin

- Used in this project as building multiple 8 bit registers with just basic logic gates is a cumbersome repetitive process not necessarily in line with the goal of the project.

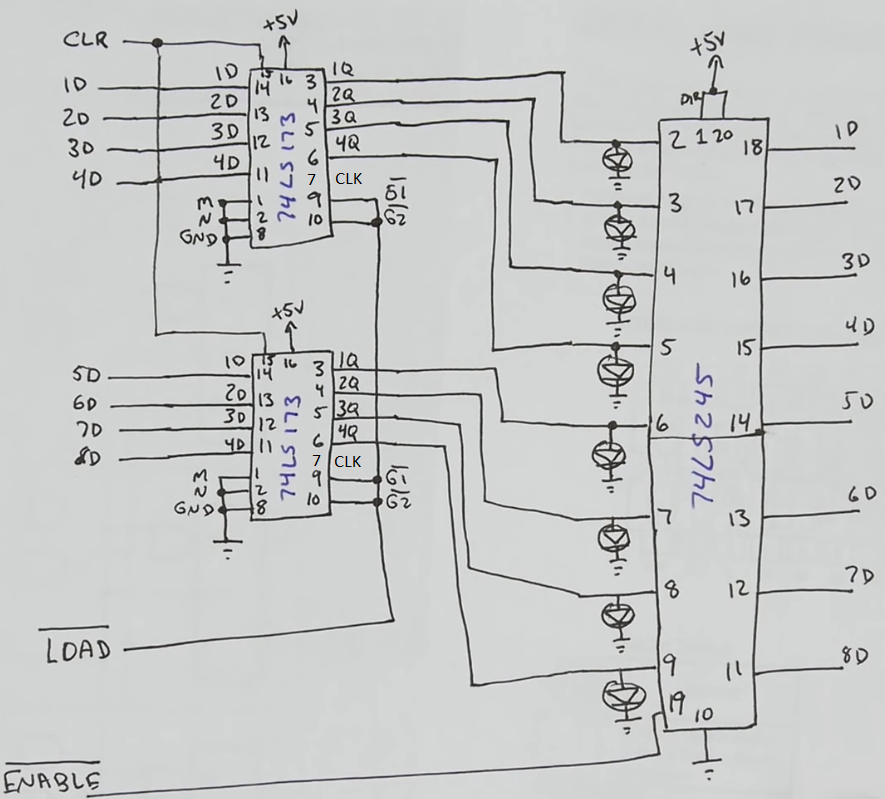

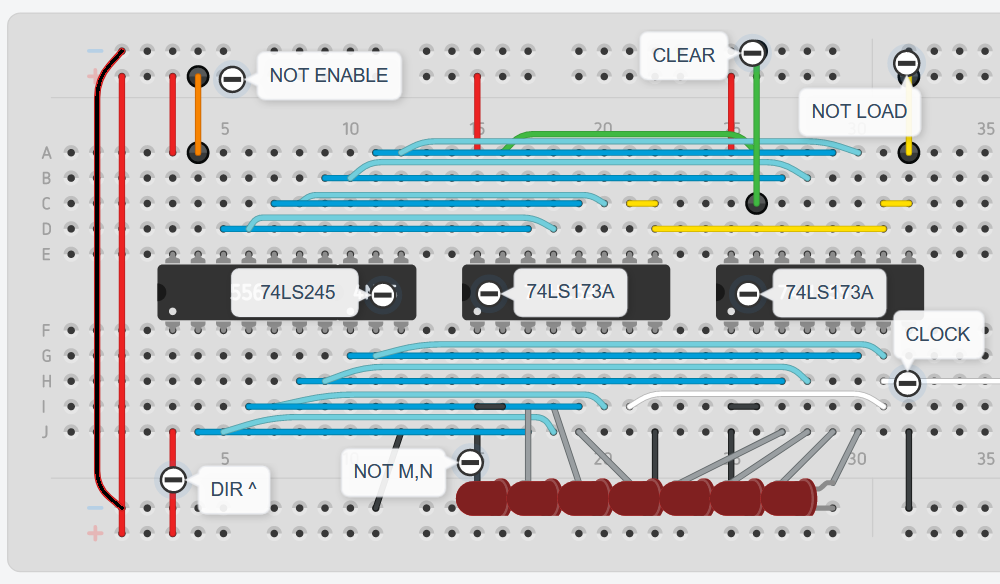

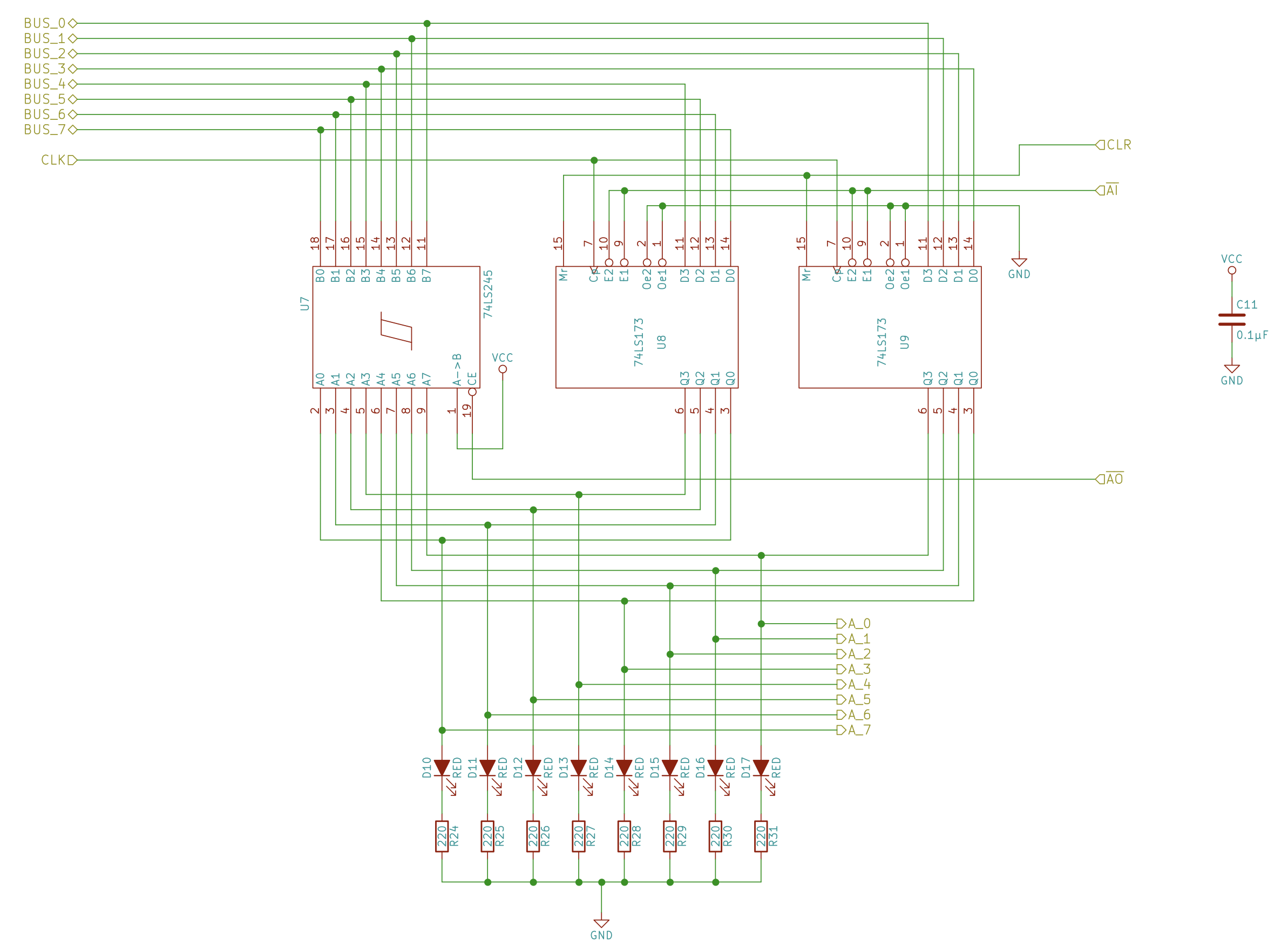

Building an 8-bit register

- We will be using 2 74LS173A chips for each 8 bit register

- It has a built-in tri-state logic gate with the default output set to be disconnected unless the output control is enabled

- Since we want to be able to see at all times what’s the value of the register, we will turn the output cotroll to be always enabled, put a LED in series, and then manually add another tri-state logic gate with the 74LS245.

- The 74LS173A requires both M and N to have 0V (grounded) to output the contents of the 4-bit

- The 74LS173A also has 2 inverted load inputs per pin, so does the enable pin of the 74LS245.

- Low \(\overline{\text{ENABLE}}\): register output is sent to the bus

- High \(\overline{\text{ENABLE}}\): register output is not sent to the bus

- Low \(\overline{\text{LOAD}}\): bus content is sent to the register

- High \(\overline{\text{LOAD}}\): bus content is not sent to the register

- If you do things right, you will never have a high load and a high enable at the same time (that is, sending to the bus and reading from the bus at the same time is an unlikely scenario)

- CLR: resets bits to 0, should be set to ground rather than open.

- DIR: we always set it high such as the the direction of the tri-state logic gate is always from

Tinkercad

- Tinkercad implementation.

- Bus to register: The inputs of the registers (who have not load pin low (load = 1) in this context) are connected to the outputs of the tri-state logic gate (who has not enable pin high (enable = 0)) that connects to the bus (light blue cables)

- Register to Bus: The outputs of the registers are always connected (M, N, pins to ground so we can see the register contents with the LEDs) to the tri-state logic gate (who has not enable pin low (enable = 1) in this context) such that it can be sent to the bus (green cables)

- Bus to register: The inputs of the registers (who have not load pin low (load = 1) in this context) are connected to the outputs of the tri-state logic gate (who has not enable pin high (enable = 0)) that connects to the bus (light blue cables)

Schematic for Register A (same as B)

- AI = Load

- AO = Enable

- \(A_n\) = input for the ALU A’s n input

Schematic for Instruction Register

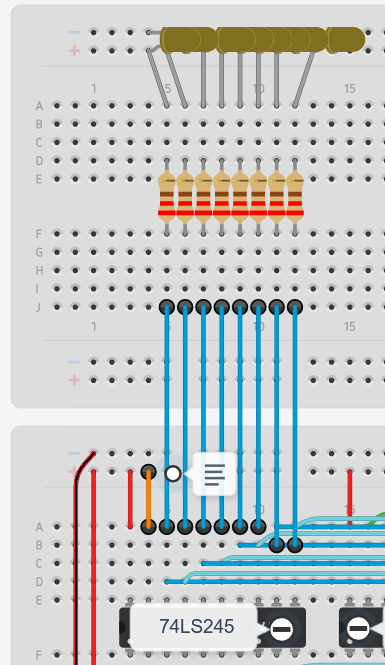

Testing the register with a temporary bus

- If there’s no connection to a bus and you set load high, the 74LS173A chip will default the inputs as high voltage as there’s typically a pull-up resistor, therefore all the bits of the register will set to 1 if there’s an open circuit with the bus

- This happened because load was high and enable was low (and since there’s only this register there’s literally no enabled bits in the bus, thus the bus is an open circuit (the input is floating and not grounded as although the Bus LEDs are connected to ground they are a diode, meaning that they are designed such that current only goes in one direction. Since the LEDs are aligned in a way to expect the current to come from the Bus, they are disallowing the situation where there are no current comming from the Bus and an input pin pull-up resistor wants to sink via the Bus leds connected to ground (that is not allowed as the LED blocks the current going that way, it essentially behaves then as an open circuit)))

- Later we will add a set of 8 \(10k\Omega\) resistors connected to the Bus and to ground to default the value of the Bus to 00000000 when there’s no party enabling the Bus.

- Since their resistane is significantly high, they should not sink in much current when the bus is enabled, thus not affecting the normal behavour of the Bus.

- Later we will add a set of 8 \(10k\Omega\) resistors connected to the Bus and to ground to default the value of the Bus to 00000000 when there’s no party enabling the Bus.

- This happened because load was high and enable was low (and since there’s only this register there’s literally no enabled bits in the bus, thus the bus is an open circuit (the input is floating and not grounded as although the Bus LEDs are connected to ground they are a diode, meaning that they are designed such that current only goes in one direction. Since the LEDs are aligned in a way to expect the current to come from the Bus, they are disallowing the situation where there are no current comming from the Bus and an input pin pull-up resistor wants to sink via the Bus leds connected to ground (that is not allowed as the LED blocks the current going that way, it essentially behaves then as an open circuit)))

- If we set the load low and the enable high we should be able to move the contents of the register to the bus

- Try to load a bus with some pins connected to ground such that the received load is a combination of 1s and 0s.

-

Then connect another register to the bus and transfer the contents (which should appear in the next clock cycle).

- My testing experience:

- The register outputs and Bus LEDs without resistors, although allowed by the LS chips, seemed to sink too much current due to their low resistance (and that next they are connected to ground), and I wasn’t able to send 8 ON bits from one register to the other until I removed the bits from the outputs and added a series \(220\Omega\) resistor to each LED in the Bus.

- Therefore my 8-bit computer will always have a resistor in series with each LED.

Instruction register

- The instruction register is identical besides that it is aestethically mirrored as we will place it on the left side of the computer

- Also it will only connect the 4 least significant bits (yellow) to the Bus, as the other 4 will connect to into the instruction decoder (next chapters)

- So you should connect A1-A4 (4 most significant bits) of the buffer to ground

- Make sure to connect to use the clock signal, which is the left leg of the RC capacitor of the RAM input module, and not the pull-down resistor.

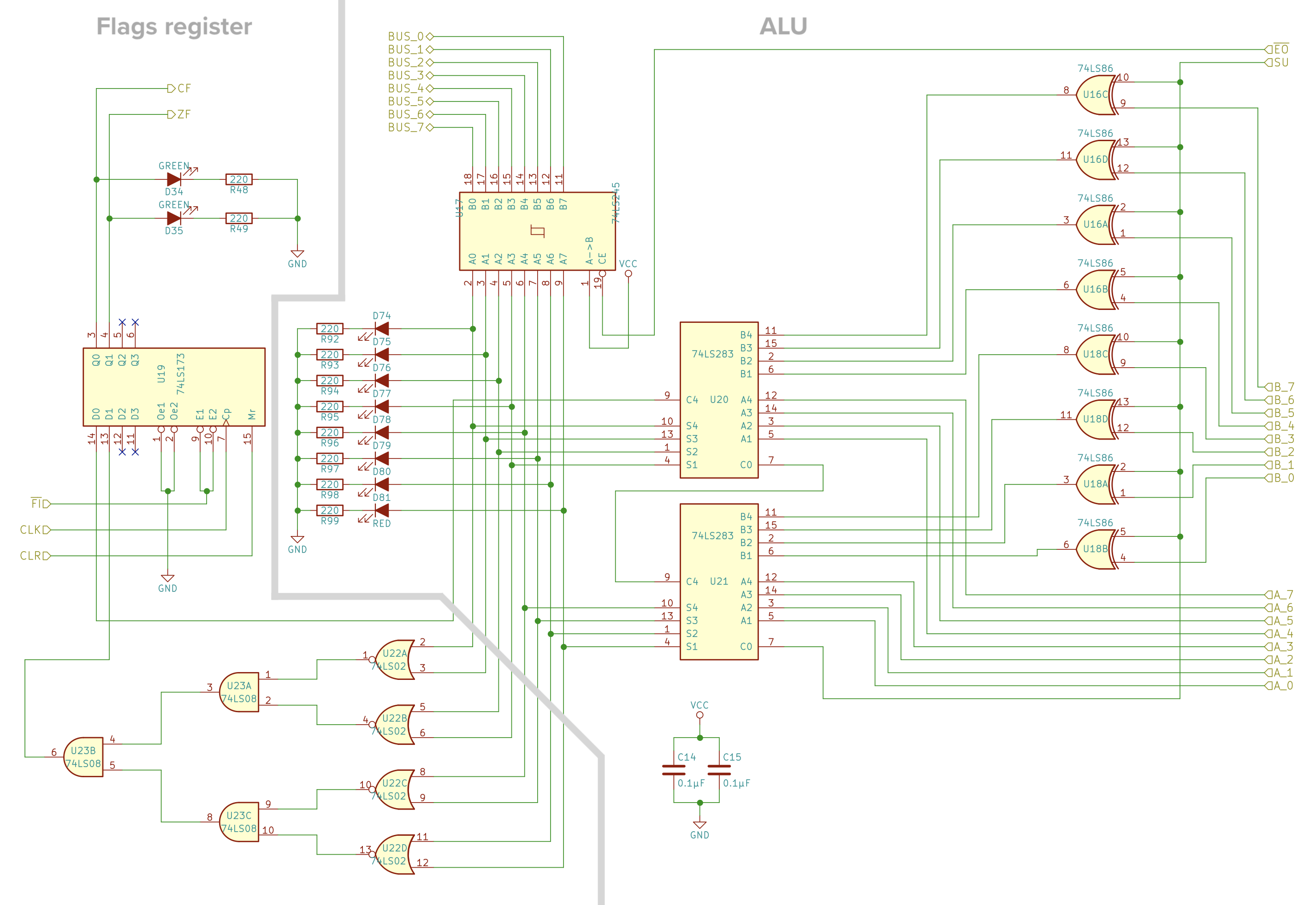

Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU)

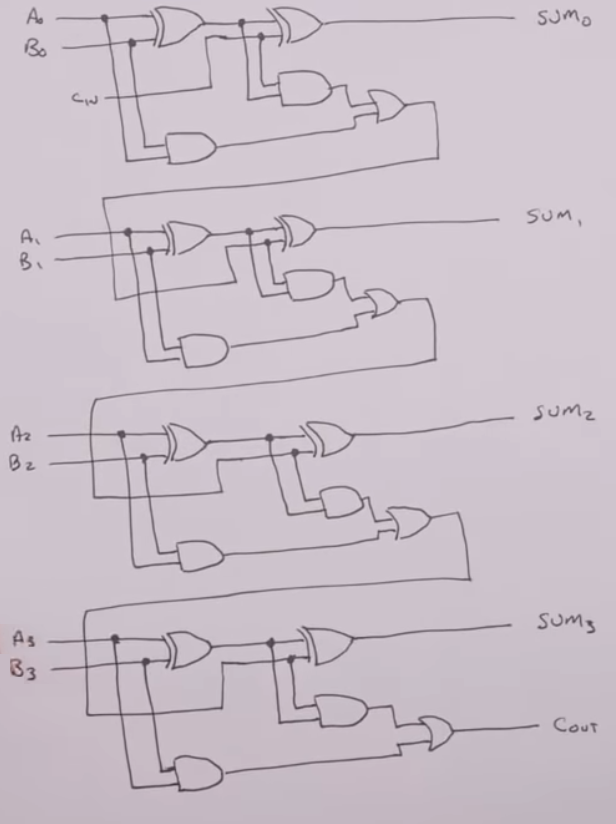

Adding numbers

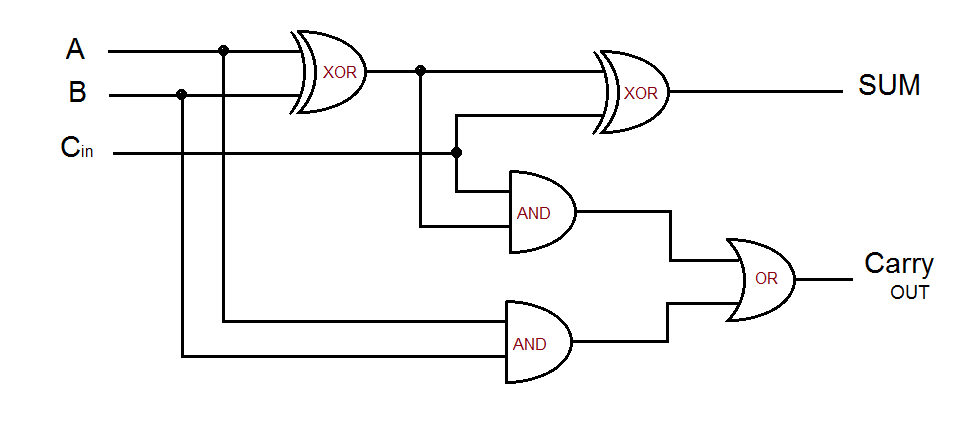

- Adding 2 bits has 4 logic variables:

- bit \(A_n\)

- bit \(B_n\)

- carry \(C_n\) also known as “carry in”

- carry \(C_{n+1}\), also known as “carry out” for \(A_{n+1} + B_{n+1}\) (and implicitly \(+ C_{n+1}\))

- You can replicate the same circuit k times to have a k-bit full adder (and use the last carry out bit to eventually display the most significant bit to not overlfow the result)

- The carry out of the adder \(n\) is the carry in of the adder \(n+1\)

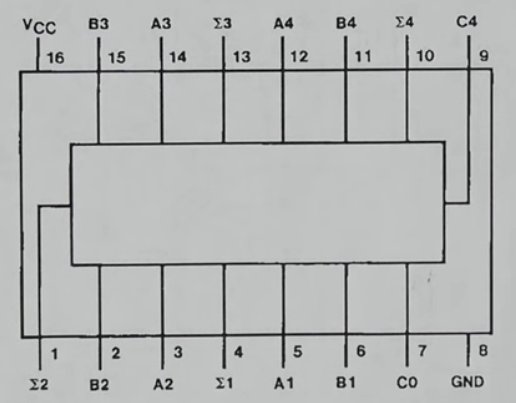

4-bit adder (74LS283)

- The 74LS283 chip implements the same logic as above.

- C0 is the carry in

- C4 is the carry out, which we can use to cascade another 74LS283 4-bit adder

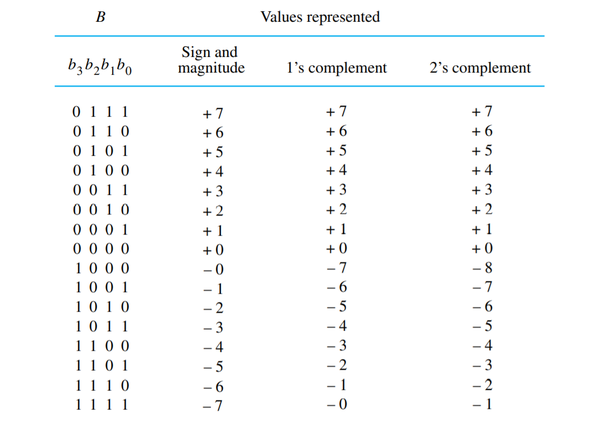

Negative numbers

- There are multiple ways to represent binary negative numbers

- Sign and magnitud: uses the most significant bit (MSB) as a sign bit, when such bit is 0 the number is positive, when the MSB is 1 the number is the same \(\cdot -1\)

- 1’s complement: Flips zeros and 1s (XOR all 1’s) to make the negative version

- 2’s complement: To make the negative version you XOR all 1’s and then XOR the least significant bit (LSB) with 1 (so 1 C’s negative + 1)

- 2’s complement is our choice to represent negative numbers since subtraction can use the same algorithm as addition.

- We just have to always ignore the last carry bit

- Overflow example: When 4 bit full adders sum 0111 (7) + 0001 (1) we end up with 1000 (-8)

- MSB is 1, so it’s negative

- flip(1000) = 0111

- XOR(1,0111) = 1000 = \(2^3\) = 8

- 1000 = -8

- MSB is 1, so it’s negative

- Therefore the range of 2’s complement is \([-2^{k-1}, 2^{k-1}-1]\)

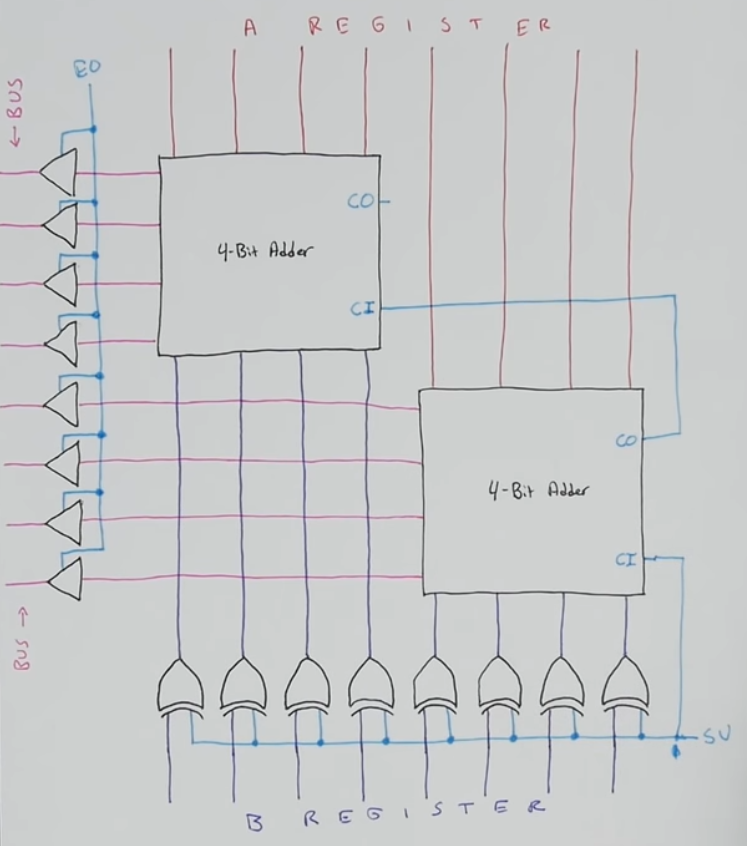

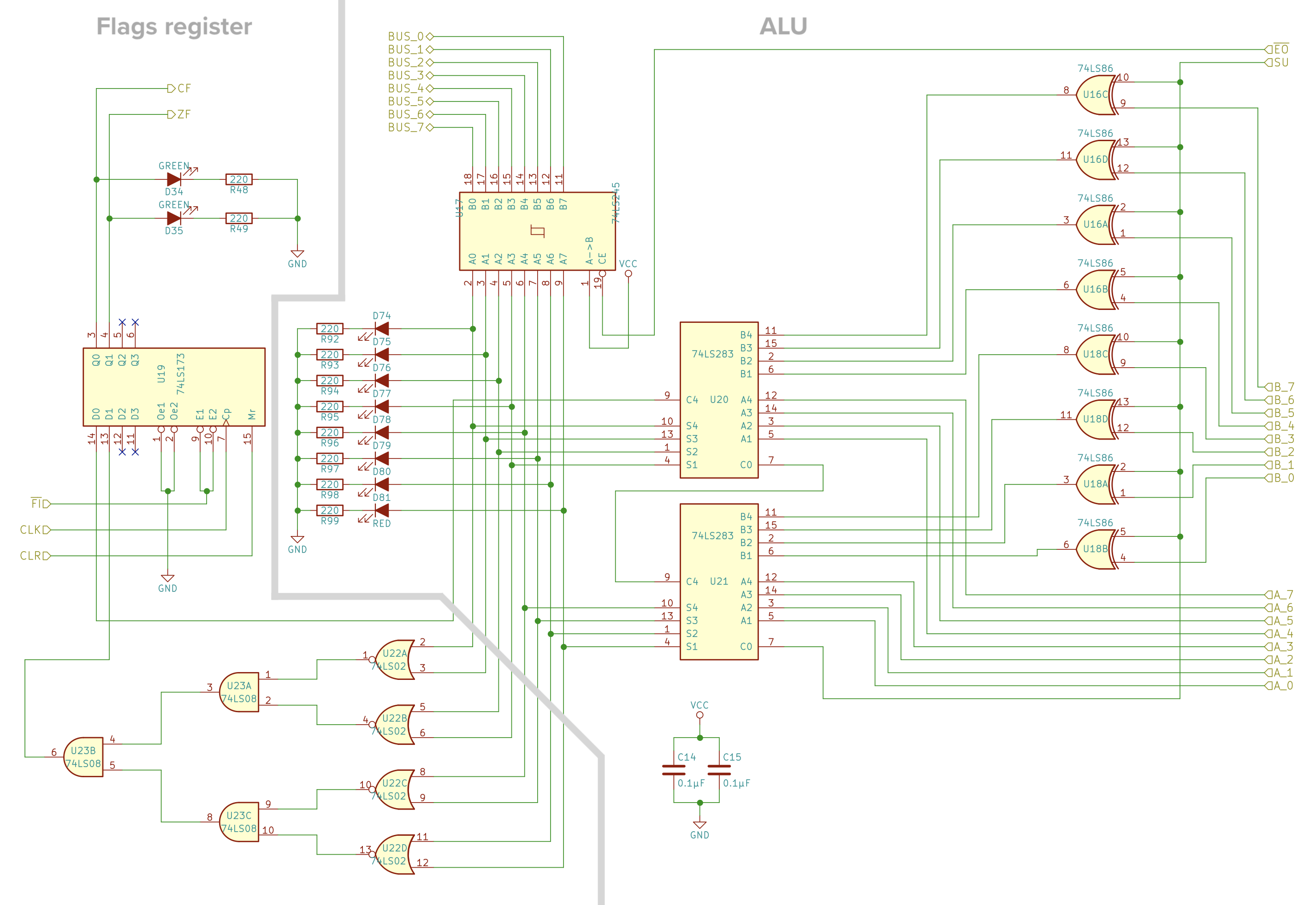

ALU design

- Our ALU will only do addition and subtraction

- We will also connect the output of registers A and B directly to the inputs of the ALU

- It will output to the Bus either:

- A+B (\(EO\))

- E symbolizes \(\Sigma\), which is the sum

- A-B (\(SU\))

- SU symbolizes “subtraction”

- A+B (\(EO\))

- AI/BI stands for load bus to A/B (load A/B input from Bus)

-

AO/BO stands for enable A/B onto the Bus (enable A/B output to Bus)

- Just like with the registers, we don’t want to connect (and sink current) to the Bus at all times. We therefore also use tri-state logic gates to output to the bus (high, low or disconnect (aka not interact))

- The XORs gates for B outputs can be triggered with a unique signal that XORs B with all 1’s such that B is inverted, then to subract A-B we only need to do A + inverted B + 1 (2’s complement sum = subtraction)

- It’d be cumbersome to implement another full adder just to sum 1.

- Instead we can use the carry in bit of the least significant 4-bits adder and connect it together with the signal to XOR all 1’s such that the adder already takes care of finishing the negation in 2’s complement of B by summing 1 each time we decide to XOR all B’s outputs

- Therefore \(EO\) and \(SU\) are not exclusive instructions:

- \(EO\) high and \(SU\) low = output A+B

- \(EO\) high and \(SU\) high = output A-B

- \(EO\) low = disconnect from Bus

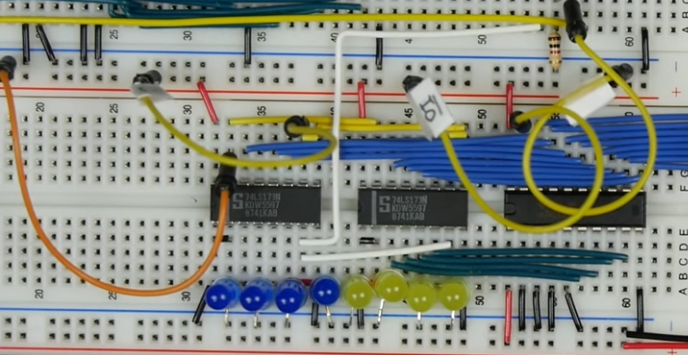

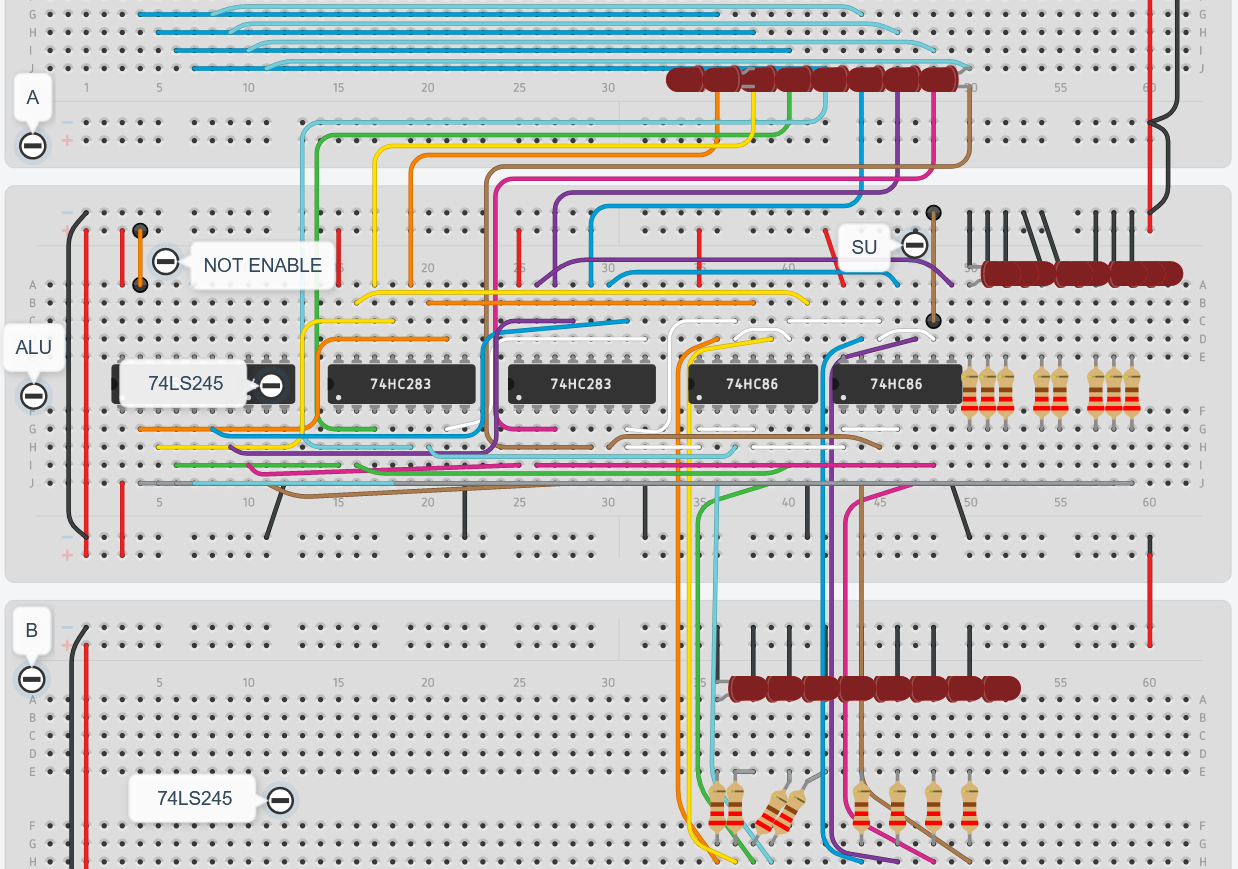

Building the ALU

- Components:

- 2 4-bit adders chips (74LS283)

- 2 XOR gates chips (74LS86)

- 1 tri-state buffer chip (74LS245)

- Steps:

- Connect power/ground pins of all ALU chips and DIR (\(V_{cc}\) to pin 1) of the tri-state buffer of the ALU

- Connect carry out of LSB adder (right C4) to carry in of MSB adder (left C0)

- Connect outputs of A register to ALU’s adders \(A_n\) inputs:

- The tri-state buffer pins of register A are BIG endian (the most significant bit (leftmost number) has the smallest address (A1)) while the adder is little endian (the least significant bit has the smallest address (A1))

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_8\ (pin\ 9) = \text{LSB adder (right) } A_1\ (pin\ 5)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_7\ (pin\ 8) = \text{LSB adder (right) } A_2\ (pin\ 3)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_6\ (pin\ 7) = \text{LSB adder (right) } A_3\ (pin\ 14)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_5\ (pin\ 6) = \text{LSB adder (right) } A_4\ (pin\ 12)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_4\ (pin\ 5) = \text{MSB adder (left) } A_1\ (pin\ 5)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_3\ (pin\ 4) = \text{MSB adder (left) } A_2\ (pin\ 3)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_2\ (pin\ 3) = \text{MSB adder (left) } A_3\ (pin\ 14)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_A A_1\ (pin\ 2) = \text{MSB adder (left) } A_4\ (pin\ 12)\)

- The tri-state buffer pins of register A are BIG endian (the most significant bit (leftmost number) has the smallest address (A1)) while the adder is little endian (the least significant bit has the smallest address (A1))

- Connect outputs of the adders to the tri-state gate inputs (of the ALU module):

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_8\ (pin\ 9) = \text{LSB adder (right) } \Sigma 1\ (pin\ 4)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_7\ (pin\ 8) = \text{LSB adder (right) } \Sigma 2\ (pin\ 1)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_6\ (pin\ 7) = \text{LSB adder (right) } \Sigma 3\ (pin\ 13)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_5\ (pin\ 6) = \text{LSB adder (right) } \Sigma 4\ (pin\ 10)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_4\ (pin\ 5) = \text{MSB adder (left) } \Sigma 1\ (pin\ 4)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_3\ (pin\ 4) = \text{MSB adder (left) } \Sigma 2\ (pin\ 1)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_2\ (pin\ 3) = \text{MSB adder (left) } \Sigma 3\ (pin\ 13)\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_{ALU} A_1\ (pin\ 2) = \text{MSB adder (left) } \Sigma 4\ (pin\ 10)\)

- Connect outputs of B register to one of the inputs of XOR gates

- For simplicity, connect MSB bit with left XOR input B4:

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_8\ (pin\ 9) = \text{right XOR input } 1B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_7\ (pin\ 8) = \text{right XOR input } 2B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_6\ (pin\ 7) = \text{right XOR input } 3B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_5\ (pin\ 6) = \text{right XOR input } 4B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_4\ (pin\ 5) = \text{left XOR input } 1B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_3\ (pin\ 4) = \text{left XOR input } 2B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_2\ (pin\ 3) = \text{left XOR input } 3B\)

- \(\text{Buffer}_B A_1\ (pin\ 2) = \text{left XOR input } 4B\)

- For simplicity, connect MSB bit with left XOR input B4:

- Connect all other inputs of the gates together (A inputs), as well as the “carry in” of the least significant adder (right C0)

- Connect a jumper wire connected to these conections to either \(V_{cc}\) or ground (this is our subtract signal)

- Connect outputs of XOR gates to adders \(B_n\):

- Remember to pair whichever XOR gate had Buffer B1 as an input with the MSB (left) adder B4 pin, etc.:

- \(\text{left XOR output 1} = \text{LSB adder (right) input } B_1\ (pin\ 6)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 2} = \text{LSB adder (right) input } B_2\ (pin\ 2)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 3} = \text{LSB adder (right) input } B_3\ (pin\ 15)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 4} = \text{LSB adder (right) input } B_4\ (pin\ 11)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 1} = \text{MSB adder (left) input } B_1\ (pin\ 6)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 2} = \text{MSB adder (left) input } B_2\ (pin\ 2)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 3} = \text{MSB adder (left) input } B_3\ (pin\ 15)\)

- \(\text{left XOR output 4} = \text{MSB adder (left) input } B_4\ (pin\ 11)\)

- Remember to pair whichever XOR gate had Buffer B1 as an input with the MSB (left) adder B4 pin, etc.:

- Connect enable jumper wire for the tri-state buffer

- Set the direction pin of the tri-state buffer high

- Connect the output of the tristate buffer of the ALU to the Bus

- Optional: hookup LEDs to the tristate buffer inputs of the ALU

Tinkercad

Schematic

- The flags register portion of the schematic is described later on as part of the CPU control logic.

Testing the ALU

- Because the registers only load from the Bus at clock rise, if we ENABLE the ALU onto the Bus and LOAD the Bus onto a register, when we advance 1 clock cycle this will happens. If we are adding:

- at t0 (before advancing clock cycle) the Bus shows A+B (let’s say)

- then at t1:

- register A = ALU at t0

- ALU = A (which is ALU at t0) + B

- Bus = ALU (which is ALU at t0) + B

- This is basically Bus += b at each clock cycle

- If we only have LEDs hooked up to the bus, we can debug B++, A++, and B– in a similar fashion

- 1 clear the contents of both registers

- Load all 1s to register A (by having high load and nobody enabling the bus)

- Load all 1s except the least significant bit (by connecting that bit on the bus to ground) in register B

- The subtraction should be \(-1 –2 = 1\)

- Clear both registers and load the Bus (which has number 1) onto the register that you want to test (and its connection with the ALU)

- Peform the steps mentioned at the beginning of this section, and do all permutations of (A/B clear, the other with 1) x sum/subtract

- A– cannot be tested since only the sign of B can be changed with the SU signal

- Then you can also utilize the random D-latch starting values to generate test cases from those random boot register values with almost no setup costs.

Random Access Memory (RAM)

- Components in the kit (including the program counter)

- 4 Breadboards

- 1 74LS00 quad NAND gate

- 2 74LS04 hex inverter

- 4 74LS157 quad 2-1 line mux (multiplexer)

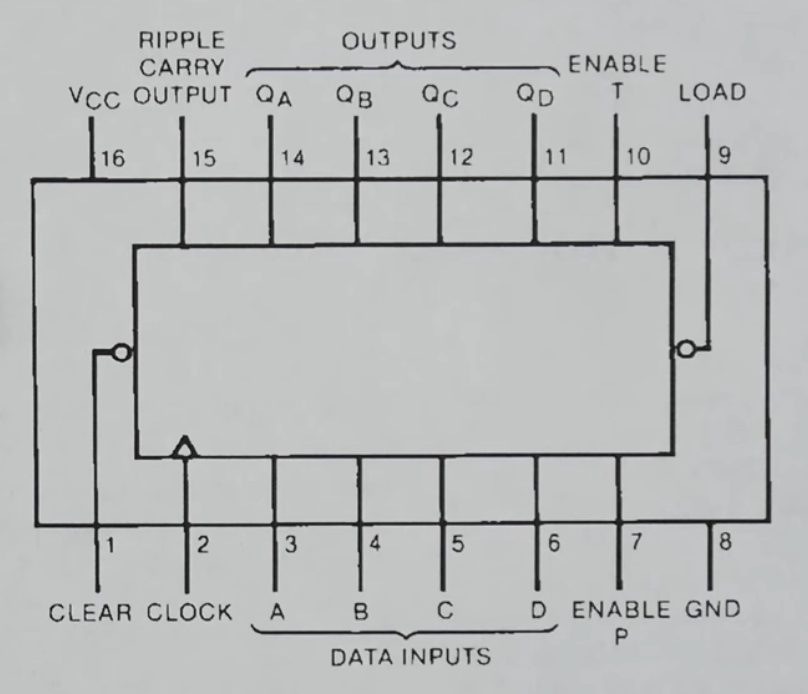

- 1 74LS161 4-bit binary counter

- 1 74LS173 4-bit D register

- 2 74LS189 64-bit RAM

- 2 74LS245 8-bit bus transceiver

- 1 Pushbutton

- 1 Slide switch

- 1 4-position DIP switch

- 1 8-position DIP switch

- 20 \(220\Omega\) resistors

- 5 \(1k\Omega\) resistors

- 10 Red LEDs

- 10 Green LEDs

- 10 Yellow LEDs

- 5 \(0.01\mu F\) capacitors (103 code)

- 5 \(0.1\mu F\) capacitors (104 code)

- The random access memory (RAM) stores the program the computer is executing as well as any data that the program needs

Register recap

- We could store 1 bit of data with an SR latch, and on top of that, require an enable signal together with S and R signals

- SR 00 = keep value

- SR 01 = 0

- SR 10 = 1

- SR 11 = illegal state

- If not enable the two AND gates always yield SR 00 (keep value)

- A D-latch replaces the SR signals with a single data signal (D) which has 2 branches, the one that keeps the same signal goes to S gate, the inverted one goes to R. On top of that we can keep the enable signal with the same logic as before.

- This logic means that now we can still do SR 00 (low enable), SR 01 and SR 10 as before but not the illegal state SR 11 (which is a good thing to avoid that scenario as it serves no purposes and it’s impredictible).

- A D flip flop is an upgraed D-latch that only sets/resets a bit at a clock pulse (useful feature for better synchronization and less noise bugs)

- We can group several flip flops together to make a register

- \(D_n\) = Input for bit n (usually connected to the Bus)

- \(\text{LOAD}\) = write onto the register signal (a separate “enable” signal independent from the clock signal, as the latter is already given explicitly by the arrow in the bottom left corner of the D flip flop box symbol)

- To finalyze the register we need an output signal that generally allows the register to output each of its bits to the Bus, to do so we use tri-state gates as we want all other outputs of the components not loading the bus to be disconnected from the Bus to avoid conflicts (we dont want a high signal from B overloading a low signal from A nor a low signal B sinking a high signal from A)

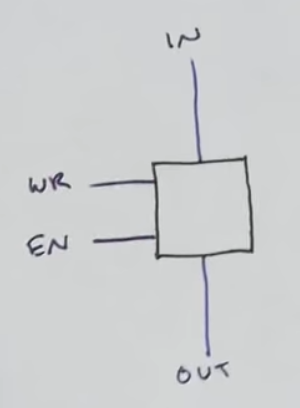

- In this context “IN” would be Q of a D flip flop of a register.

- A one bit register can be summarized with the symbol below

- An 8 bit register:

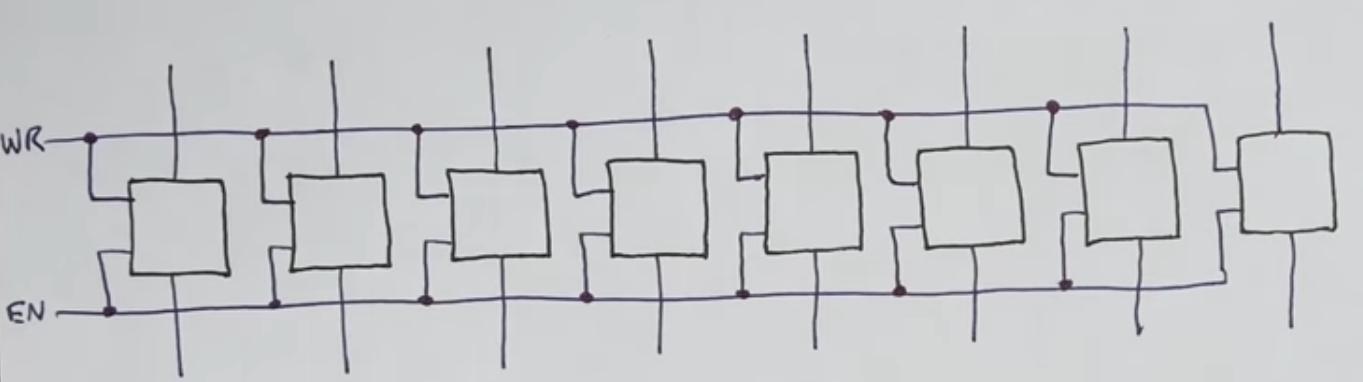

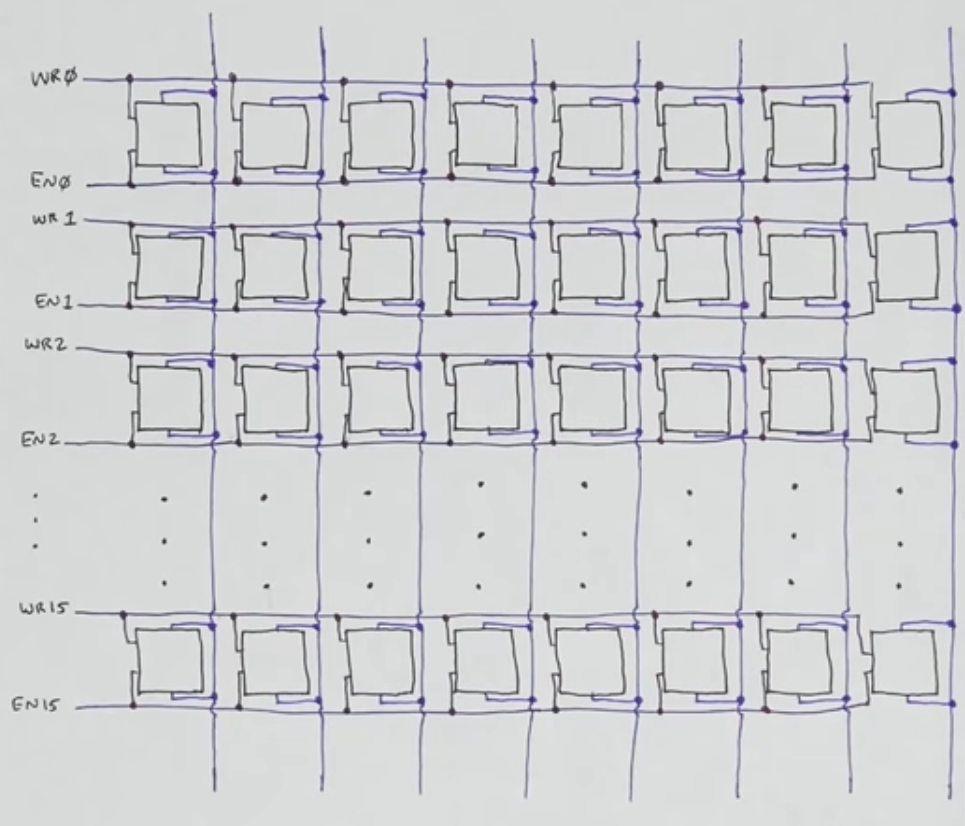

- A 16 byte ram would essentially be sixteen 8-bit registers packed into 1 chip

- With 16 write/enable (y-axis) and 8 (8 bits = 1 byte) data signals (x-axis)

- Each of those 16 registers (row), can be given a binary address and together with a decoder we can provide the high voltage signal to the specific register only.

- The decoder logic is great because in the context of chips, we can have a decoder inside and limit the amount of external pins needed for the users to specify an address.

DRAM vs SRAM

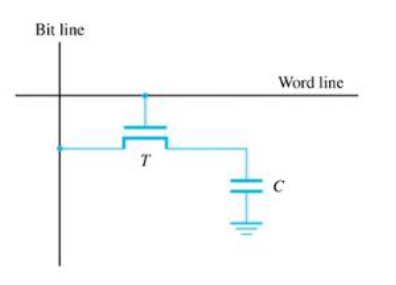

- Each of the bit cells that make up our RAM can be stored in a simpler circuit than a flip flop with just a transistor and a capacitor

- When the capacitor is charged and the address is enabled (word line) the bit voltage is high

- When the address is enabled and the capacitor is not charged it behaves like a piece of wire with 0 voltage drop, and since it’s connected to ground the bit voltage is low

- Drawback: Overtime the capacitor discharges and can only store bits for a few seconds. It also has destructive read as each time we read the content of the bit we are sinking the voltage of the capacitor, so it must be recharged immedeately after reading

- Workaround: have a seperate circuit that constantly reads and rewrites the value of the cells.

- From here comes the name Dynamic RAM or DRAM (it dynamically refreshes the data each time)

- On the other hand a D-latch keeps the data all the time just by keeping the enable signal low, which guarantees SR 00 and the NOR gates will keep the same value (even if the bit is 1, and we have SR and enable to be 0 the NOR gates have an implicit connection to \(V_{cc}\) to output 1 if the logic circuit says so without violating the principle of conservation of energy). This is regarded as static RAM or SRAM, and it’s the one our computer uses

- SRAM is generally more expensive than DRAM because you need more transistors (because of the more complex circuit logic)

- SRAM is generally faster than DRAM

- We are using SRAM because we dont want to build the refresh circuit (although in a larger scale computer it is more convinient to have a cheaper DRAM and a refresh circuit)

Difference between registers and memory

- “Memory” generally regards to RAM

- The basic difference between the register and memory is that the register holds the data that CPU is currently processing whereas the memory (RAM) holds program instruction and data that the program requires for execution.

- Furthermore, typical registers are:

- Data register: holds the operands to be operated by the processor.

- Such as our A and B registers

- Memory Address register: holds the adress of a memory location

- Accumulator: holds the result computed by the ALU

- For us the output of the ALU itself is already connected to the bus

- Instruction register: holds the instruction code (and operand) that is currently being executed.

- Program Counter: holds the address of instruction that gets loaded in the fetch cycle and then points to the next address to be executed while the former one is being executed.

- Temporary Register: holds the temporary intermediate result computed by the processor.

- Input Register: holds the input character received from an input device and delivered it to the Accumulator.

- Not implemented

- Output Register: holds the output character received from Accumulator and deliver it to the output device.

- The register for our decimal display

- Data register: holds the operands to be operated by the processor.

- Furthermore, typical registers are:

- Usually the RAM is deliberately placed close or inside the “processor” (what physically constitutes being inside/outside the processor chips depends on the manufacturer and it changes over the years), but historically the RAM would be farther from the CPU than the registers, the RAM is also bigger and slower.

- RAM is called “random” because if you choose a random address (via the multiplexer) it will take the same time to read/write for all addresses as opposite to secondary memory (magnetic, optical and flash), where the time required to read and write data varies depending on the physical location of the address due to mechanical limitations such as media rotation speeds and arm movement.

- Secondary memory keeps data even when there’s no power (as opposed to the SR latches that the registers use that start with a new random value at every circuit step response). It can only be processed by the CPU by copying it first into primary memory (as opposed to RAM that can be accessed directly via the Bus) via I/O channels.

- RAM is called “random” because if you choose a random address (via the multiplexer) it will take the same time to read/write for all addresses as opposite to secondary memory (magnetic, optical and flash), where the time required to read and write data varies depending on the physical location of the address due to mechanical limitations such as media rotation speeds and arm movement.

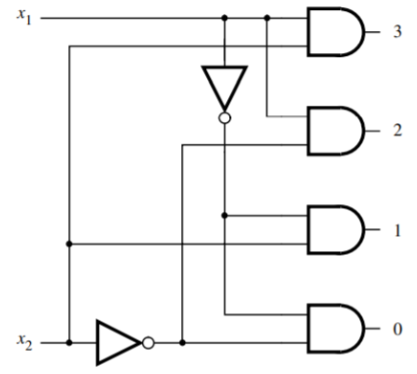

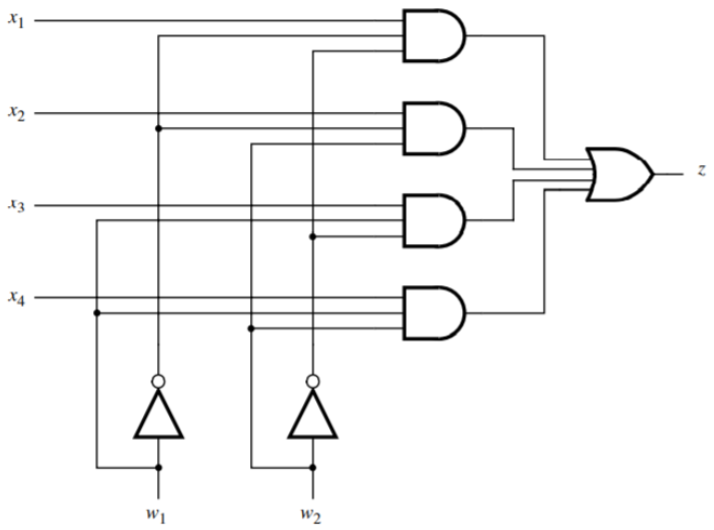

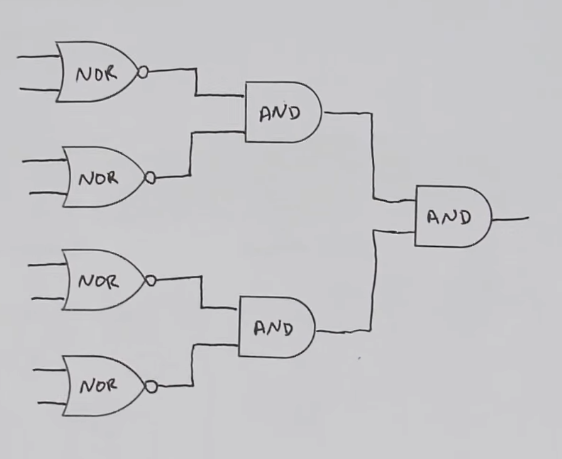

Address decoder

- With a decoder the total number of address selection pins required is \(log_2(\text{total address count}\)), i.e. (the 16th address, starting at 1st address = 0000, would be 1111)

- Do not confuse a decoder with a multiplexer. The multpilexer has \(n\) selection inputs with at most \(2^n\) data inputs for which then the multiplexer outputs just 1 of the data inputs (looks like a decoder with a final OR gate to just have 1 output line) (or simply said, the multiplexer is a “selector”, out of many data inputs, you only output one of ‘em (based on selector input pin(s)))

- The decoder on the other hand only has selection inputs, i.e. n, and at and at most (and generally close to) \(2^n\) outputs.

- The decoder is like if a multiplexer had all selection inputs to be high and the last XOR get gets removed and replaced by each of the incoming signals into separate output pins, of which all but one will be low.

- To build a decoder follow these 3 steps

- Provide a selection pin for each address bit and immedeately breanch out it’s inverse

- Build the output AND gates based on binary order:

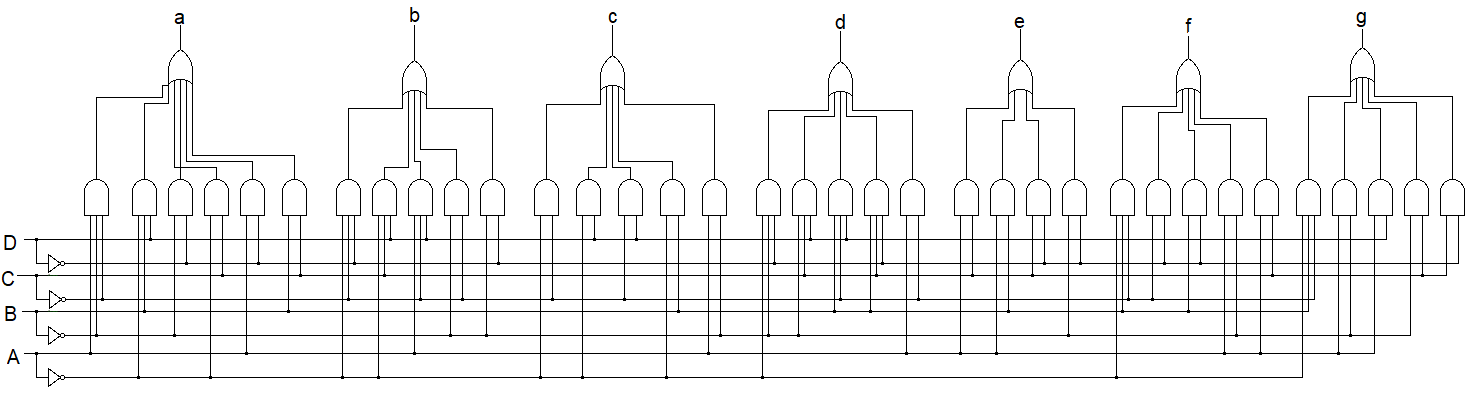

- Smallest address has all inverted pins (0s), biggest address has all non-inverted pins (1s)

- Fill the gap and map the inverted and non-inverted pins with the relevant AND gates

- The additional variable of the AND gates is reserved to the ENABLE signal (not shown in the picture) such that to enable a memory address we just need to provide the address signals and the enable signal

- To build a multiplexer you follow the same steps but on each AND gate you add a unique data input and then you XOR all the AND gates into one output signal

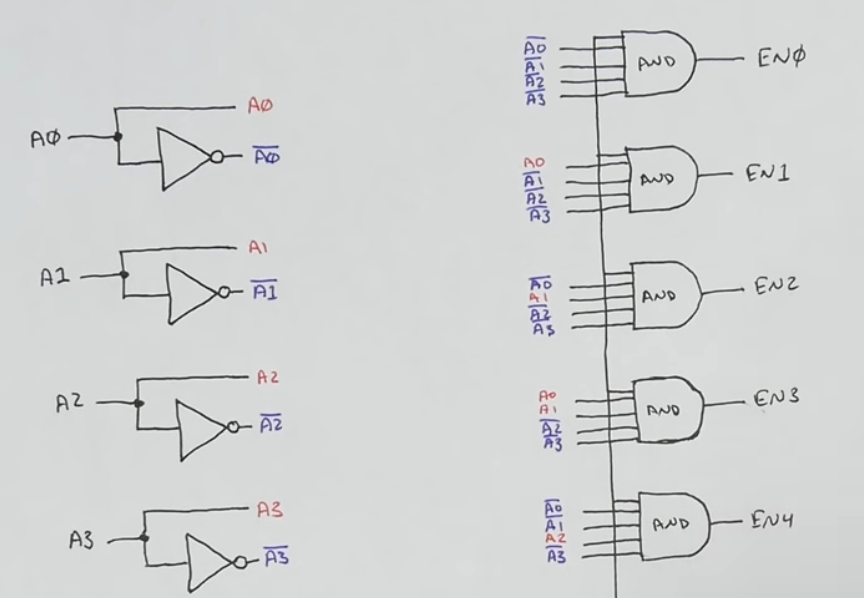

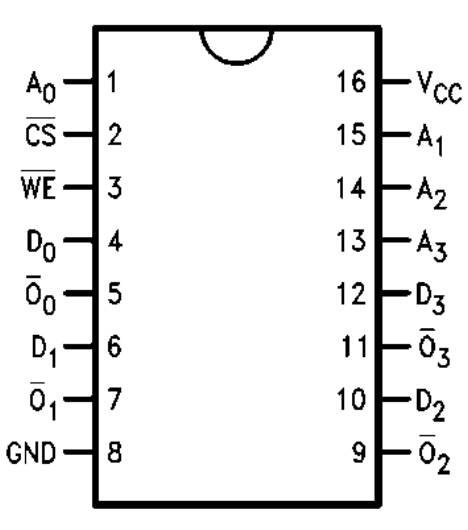

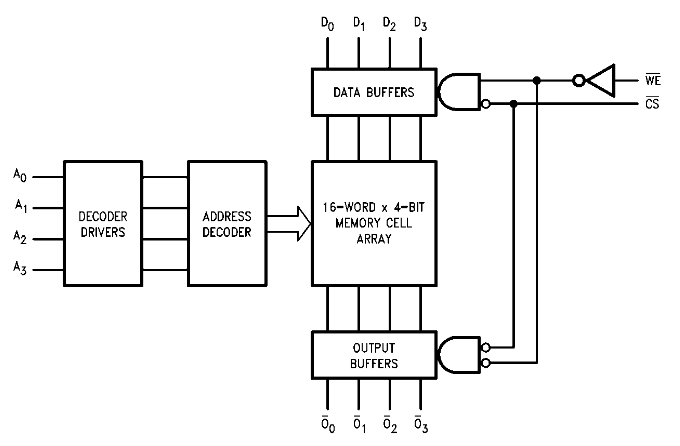

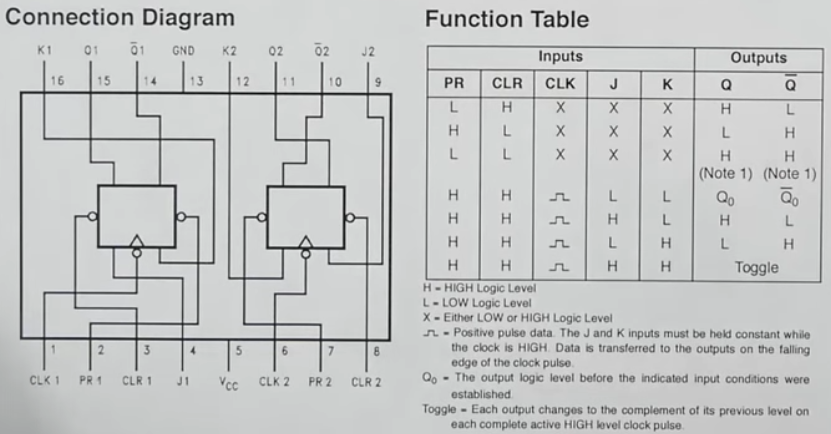

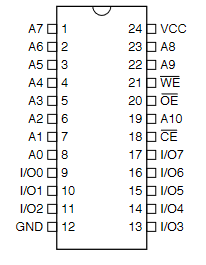

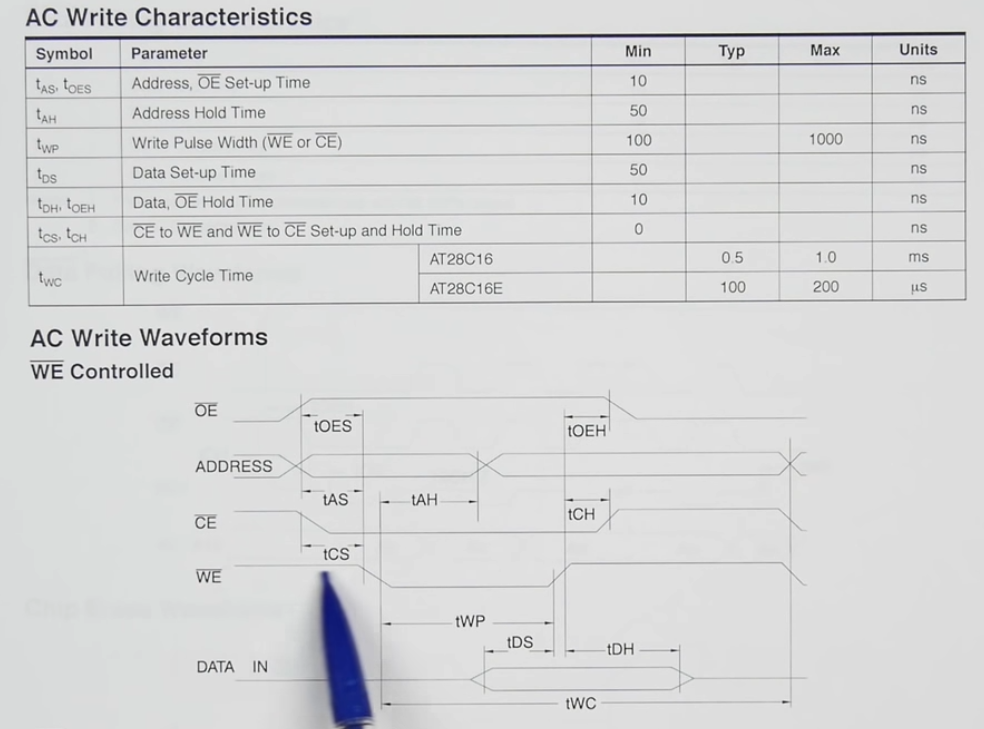

74LS189 (16 4-word address RAM)

- 64 bit random access memory

- This static RAM holds 16 4-bit words

- There are 4 An pins to address one of the 16 words (it includes an address decoder)

- We can hookup the address pins of 2 74189 4-bit word RAMs such that they share the same address signals and one chip stores the 4 MSB and the other one the 4 LSB making it a 8-bit word x 16 addresses RAM (16 byte RAM)

- The data inputs are Dn

- Output inputs are \(\overline{O_n}\), indeed they are inverted

- The outputs are active only in the Read mode, therefore while \(\overline{WE}\) is low the output LEDS might behave weirdly

- WE = write enable (loads data from the input pins and saves it to the memory given to the address pins), the pin is inverted.

- CS = chip select (enable to Bus)

- The pin is also inverted, so we will connect it to ground (such that it is always enabled so we can hookup LEDs and see its contents) and connect it to a tri-state buffer like we did with the registers. If we don’t want to hookup LEDs to the RAM, we can just use the tri-state output logic that the chip itself includes:

- \(\overline{CS}\) low & \(\overline{WE}\) low = Write

- \(\overline{CS}\) low & \(\overline{WE}\) high = Read

- \(\overline{CS}\) high = disconnect output to Bus

- I’m assuming that the inputs don’t need a tri-state buffer and can be connected all the time to the Bus since they don’t sink that much current anyway as input pins usually have around ten mega ohms of resistance.

- This part is covered here

- This part is covered here

- The pin is also inverted, so we will connect it to ground (such that it is always enabled so we can hookup LEDs and see its contents) and connect it to a tri-state buffer like we did with the registers. If we don’t want to hookup LEDs to the RAM, we can just use the tri-state output logic that the chip itself includes:

- The chip that came in the kit did not have “LS” family explcitily written and it seemed to get pretty hot during some tests with floating pins. Therefore make sure to not leave floating pins and those that are high should and be connected to \(V_{cc}\) should be with a \(1k\Omega\) pull-up resistor.

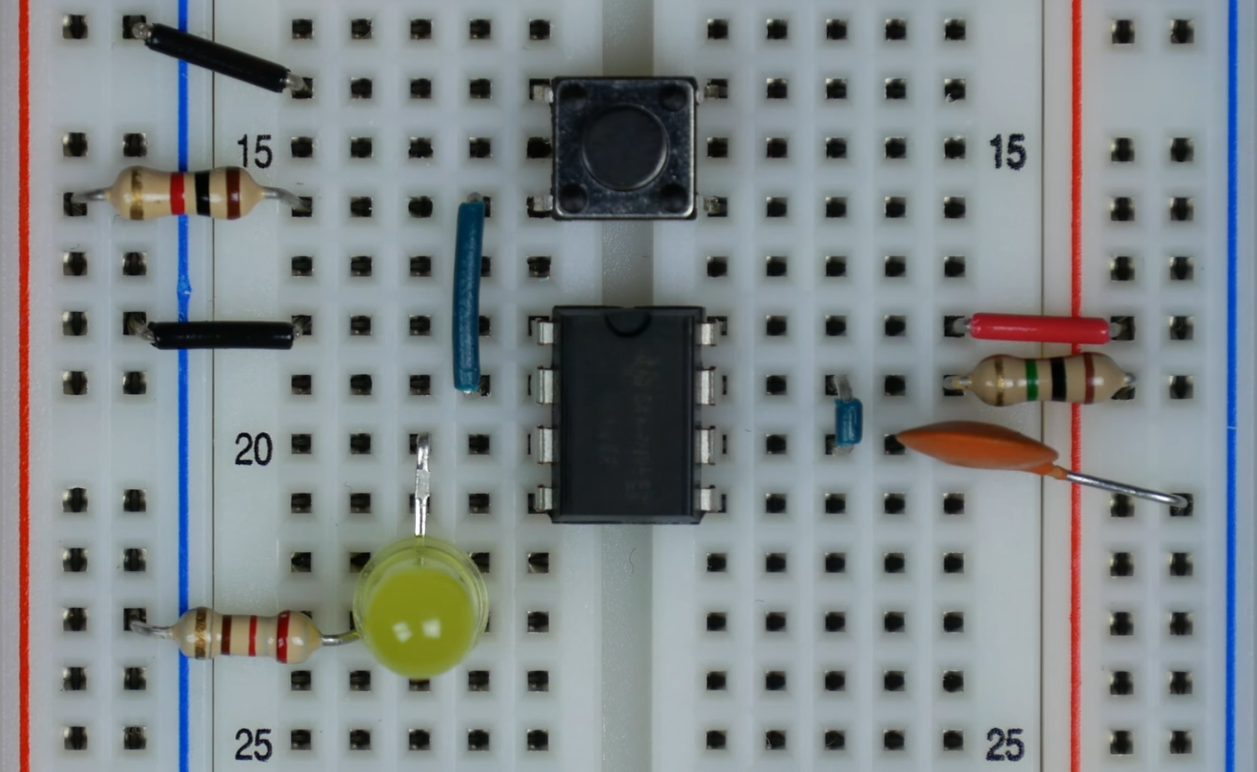

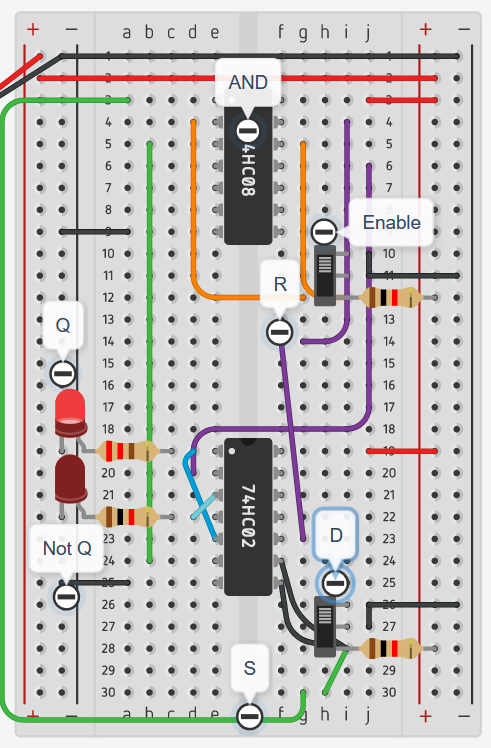

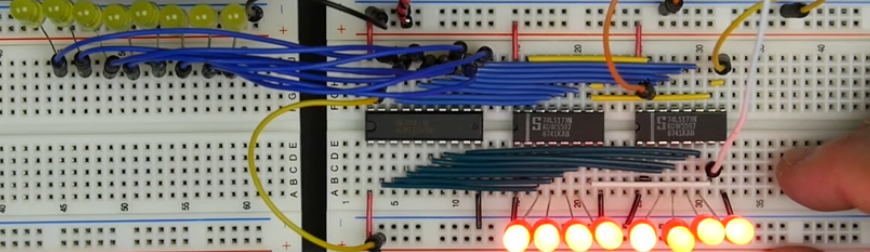

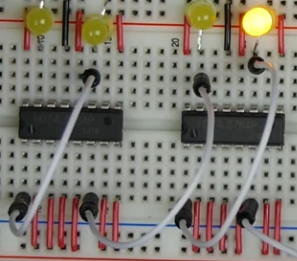

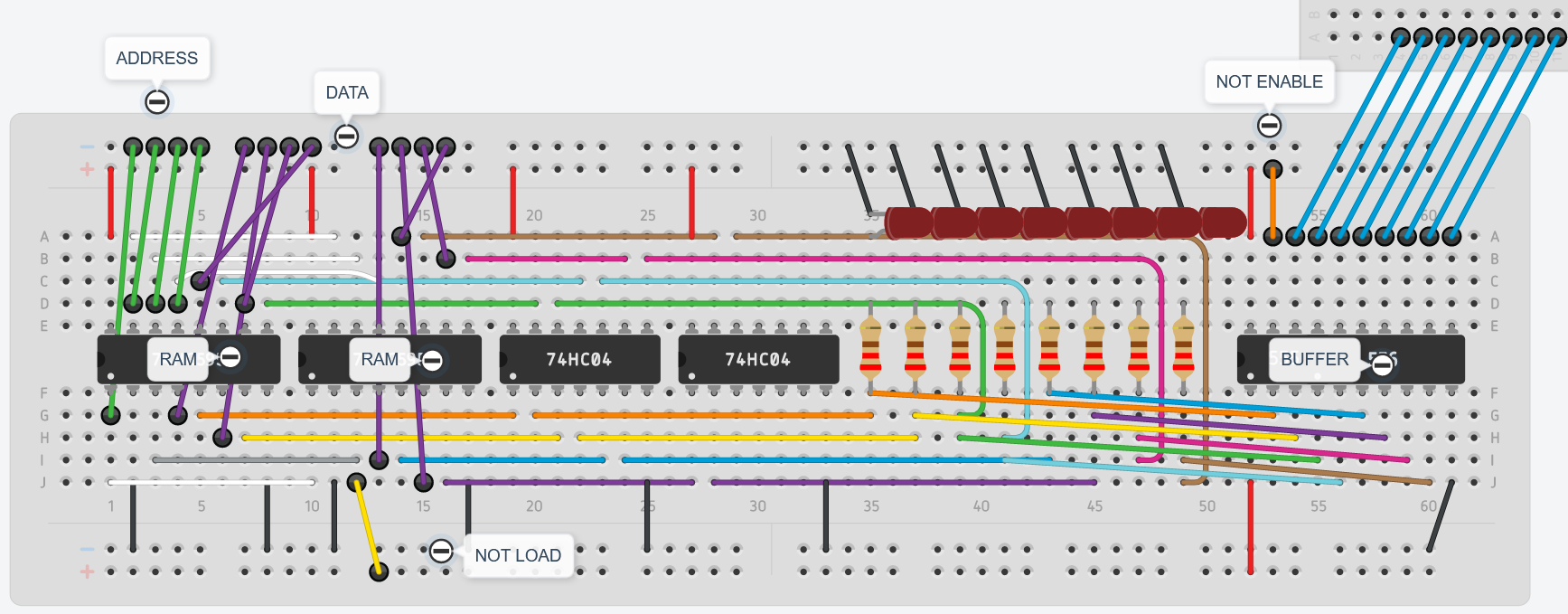

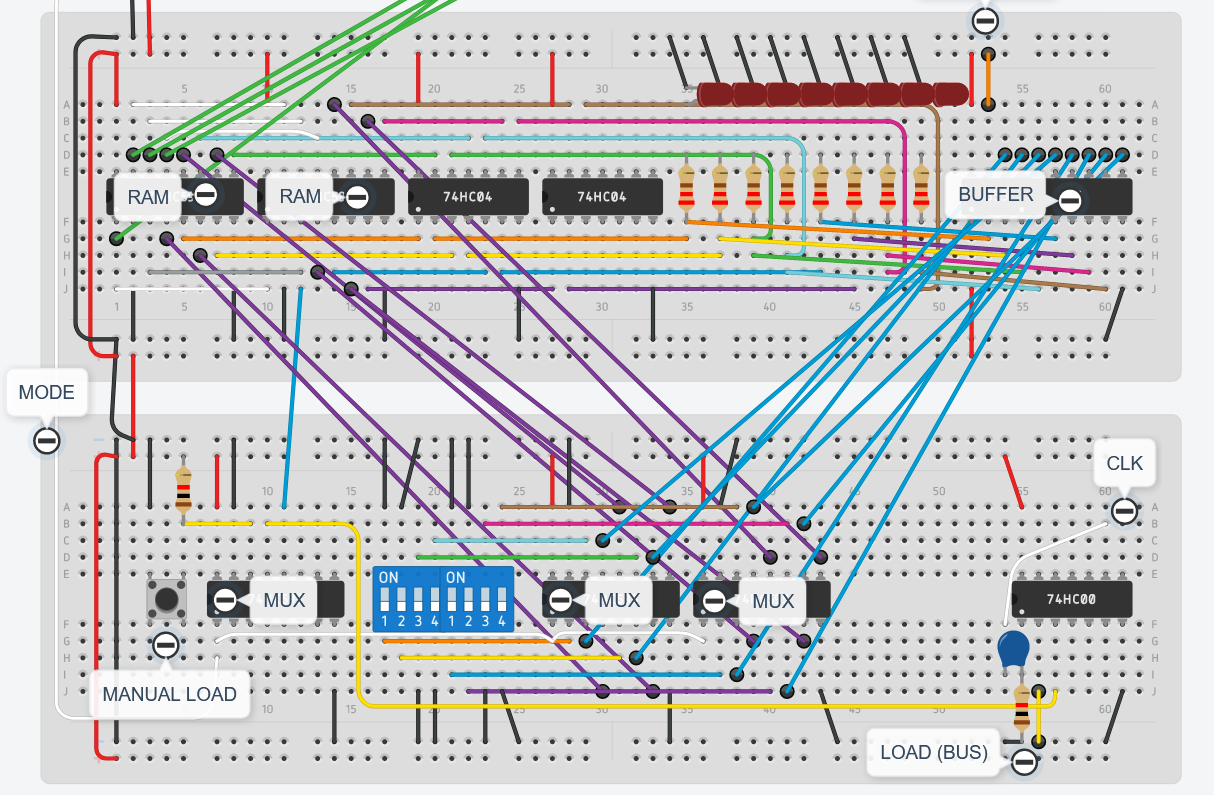

Building the RAM

- Insert chips 2 74LS189 and 2 74LS04 inverters on the breadboard and hookup the power and ground pins

- Hookup outputs of the RAM to the inverter inputs

- Hook up resistors and LEDS to the inverted-inverted outputs

- Hook up \(\overline{CS}\) to ground on both RAMS

- Insert 3-state buffer (74LS245) and connect power, ground and dir (to \(V_{cc}\)) pins

- Connect inverted-inverted outputs to the tri-state bottom pins

- Connect same address pins together from both RAMs

- Then use a jumper wire for each grouped address pin and connect it to ground as a temporary signal cable

- Connect jumper wires to each data pin as a temporary signal (later it will be connected to the DIP switches rather than to the Bus)

- Connect both \(\overline{WE}\) pins together and a jumper wire to use it as temporary signal

Tinkercad

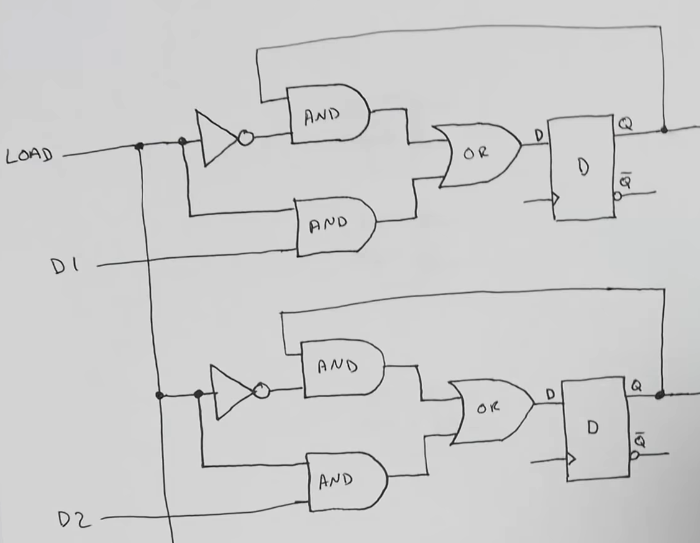

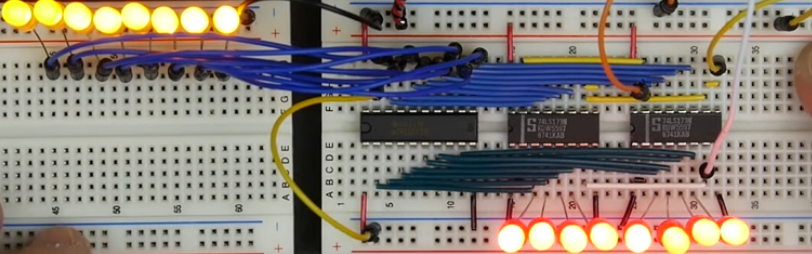

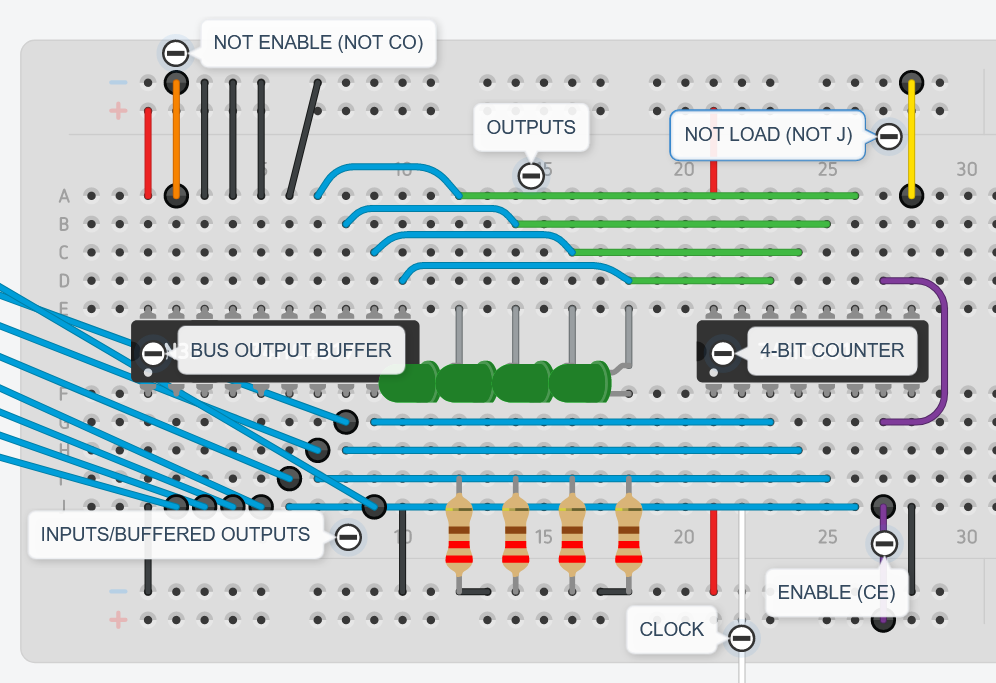

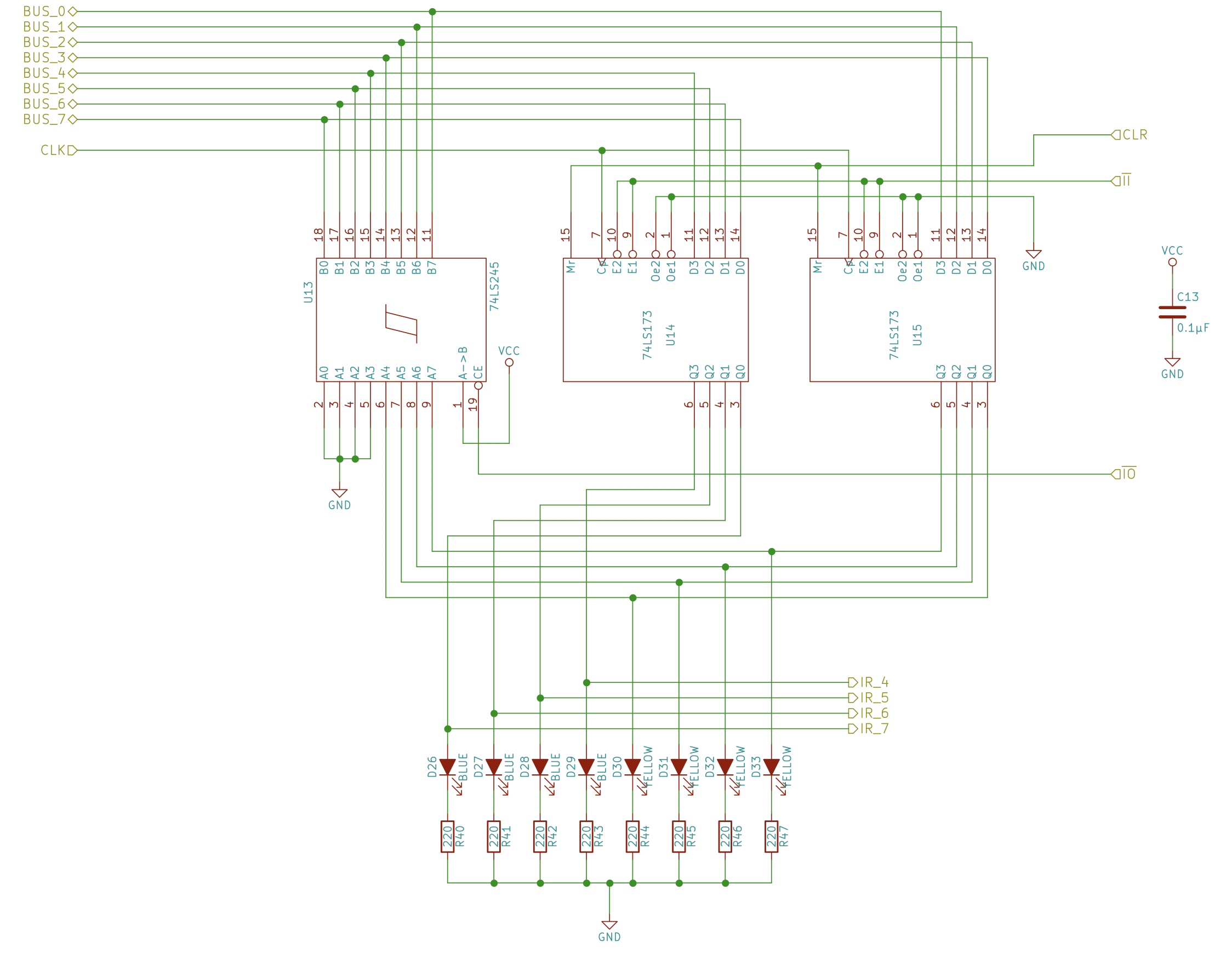

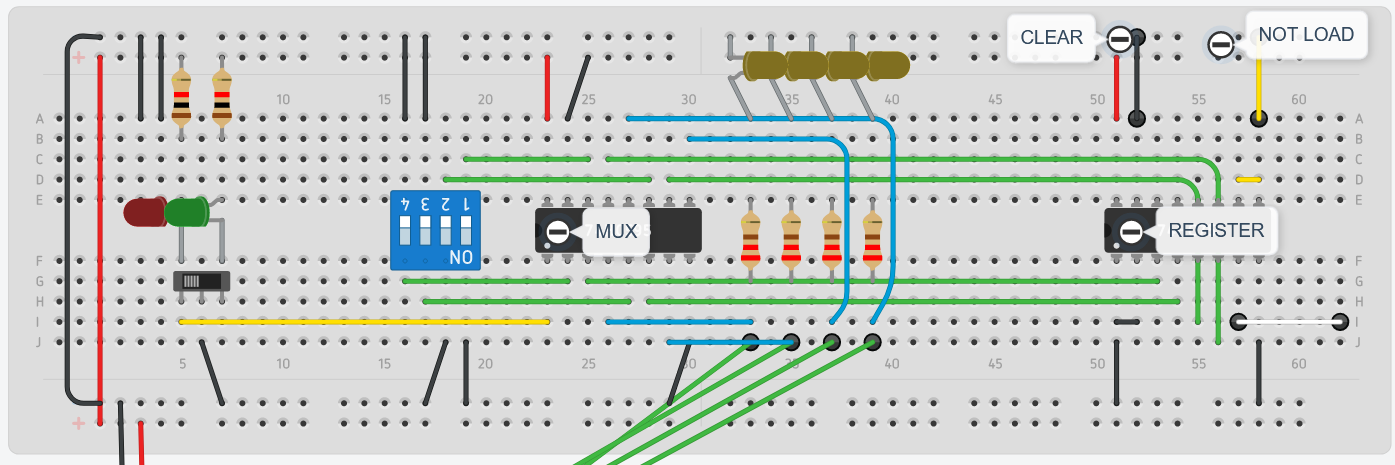

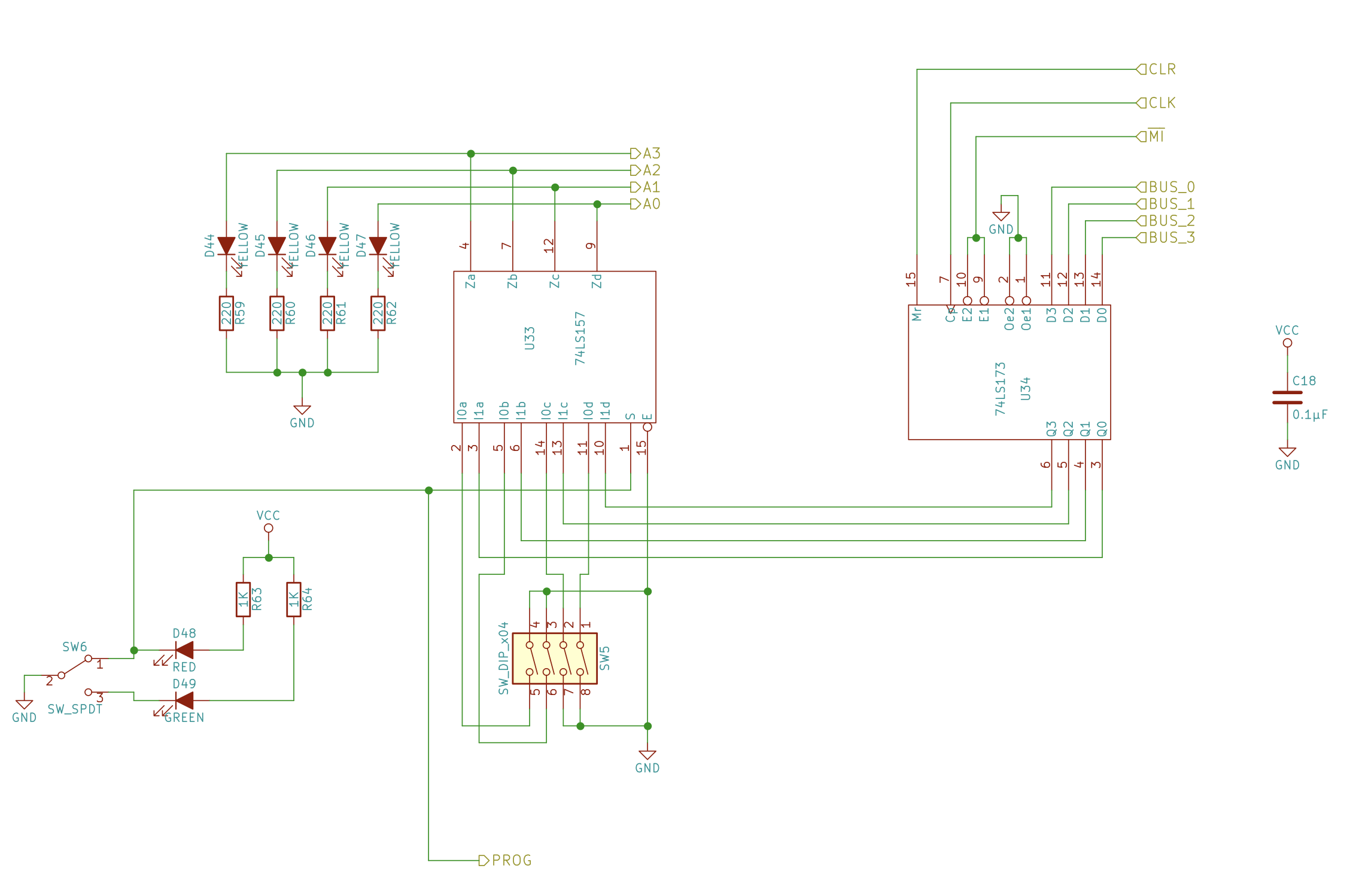

Building the memory address register (and a “programming mode” version)

- The jumper wires for the address will be connected to the outputs of the memory address register, the register that contains the current location of the RAM we’ve readily available to use

- Remove the power rails of a new breadboard and fit it between the clock breadboard and the RAM breadboard

- We’ll use a single 74LS173A (4 bit register) for the memory address register

- This register will be connected to the Bus, as we expect the computer on “running” mode to share memory addresses via the Bus, and store that value there

- The outputs of this register will be connected (via a multiplexer) to the RAM address pins

- The multiplexer would allow to chose between the memory address register and a manual switch to feed the RAM address pins

- The reason we don’t connect the Bus directly to the address pins of the RAM is that the bus can only hold 8 bits of information and if we wanted to write something on a given memory address we’d just have lost 4 bits to determine the address and thus 4 information bits to write are gonna be truncated

- Just reading the contents of a RAM address by just relying on the Bus to get the address is pin feed is problematic too as in that same clock pulse the Bus is supposed to hold the RAM address then whoever outputed that to the Bus must disable its outputs and to allow the RAM at the address specified by the Bus to output its contents. Thus getting the address and outputting the contents to the Bus just right as the other module disables its Bus output looks very complicated to implement in a reliable way, therefore we use the address register to store which ever address we need to use.

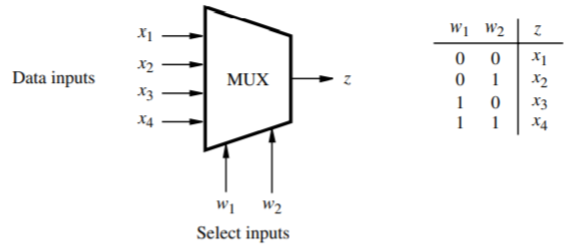

- We use a 4-bit DIP switch as the “programming mode” alternative to feed the address pins of the RAM (via the multiplexer)

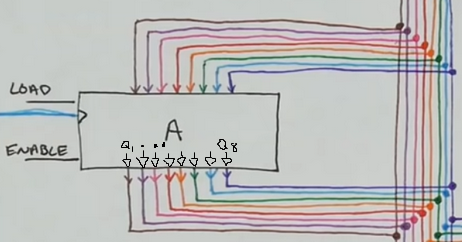

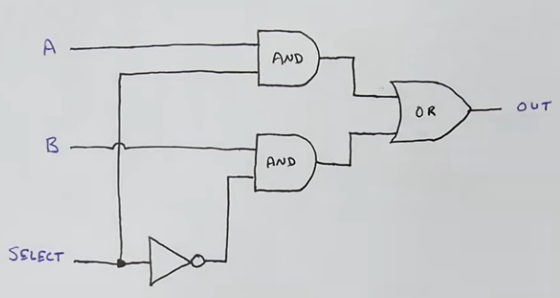

- The multiplexer logic to select between 1 bit of register address (run mode or “A”) and 1 bit of manual address (programming mode or “B”) can be described by the logic circuit below.

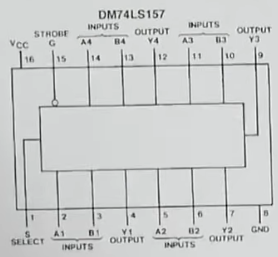

- The 74LS157 does that for us, and it has four 2-data/1-selection pins multiplexers

- The strobe pin is just an additional (inverted) control input to all AND gates, we just hook it up to ground to make the chip behave as the previosly shown multiplexer logic circuit.

- The 74LS157 does that for us, and it has four 2-data/1-selection pins multiplexers

- Implementation steps:

- Insert the DIP switch, the 74LS157 multiplexer (mux) and the 74LS173 register.

- Set power and ground pins

- Set strobe to low (mux)

- Output control (pins 1 and 2 of register, which you have to merge) to low as well (we want to always see the lights

- Connect pins 9 and 10 (not load) and a jumperwire cable to use it as a temporary signal

- Connect register clear to ground

- Connect clock pin to the clock

- Connect the outputs of the register to the B inputs of the mux

- Connect one end of the DIP switches to the A inputs of the mux, the other end to ground.

- We’ll be utilizing the fact that the default value of floating pins for the 74LS157 mux is high, therefore we alternate between ground and floating (high)

- Connect a slideswitch with common (midle pin) to ground (this is best practice), and the 2 terminals to \(V_{cc}\), each with a \(1k\Omega\) resistor and a LED

- Then the slideswitch determines which of the terminal gets to be connected to ground and thus has 0V, while the non-selected terminal has the voltage it’d have as if the slideswitch didn’t exist.

- Connect one of the terminals to the select pin of the mux, such that the terminal that you chose matches the LED pattern that you want. When the LED is shining, it actually means that the voltage of that terminal is 0V (the terminal is grounded and no more current will flow to any other branch other than back to the power source, had it not be grounded, then the votlage would have been high)

- The datasheet of the 74LS157 shows that the select pin is inverted, so a lighting LED terminal (with 0V) is eventually a high select, which then selects A inputs (DIP switch). Therefore programming mode will be equal to the (lighting) LED whose terminal is connected to the select pin of the mux (pin 1)

- Connect the outputs of the 74LS157 to 4 address LEDs (with 220 resistors)

- Connect the outputs of the 74LS157 to the RAM address pins

Tinkercad

Schematic

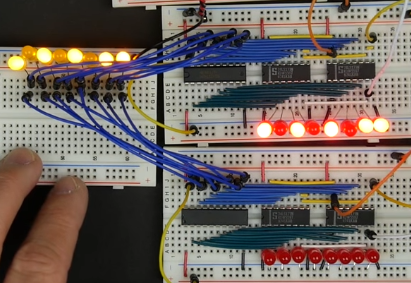

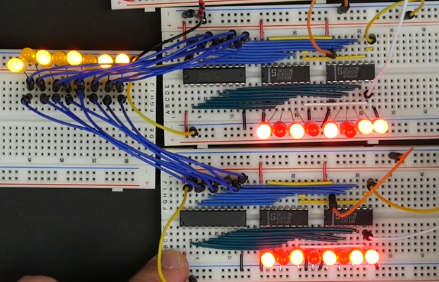

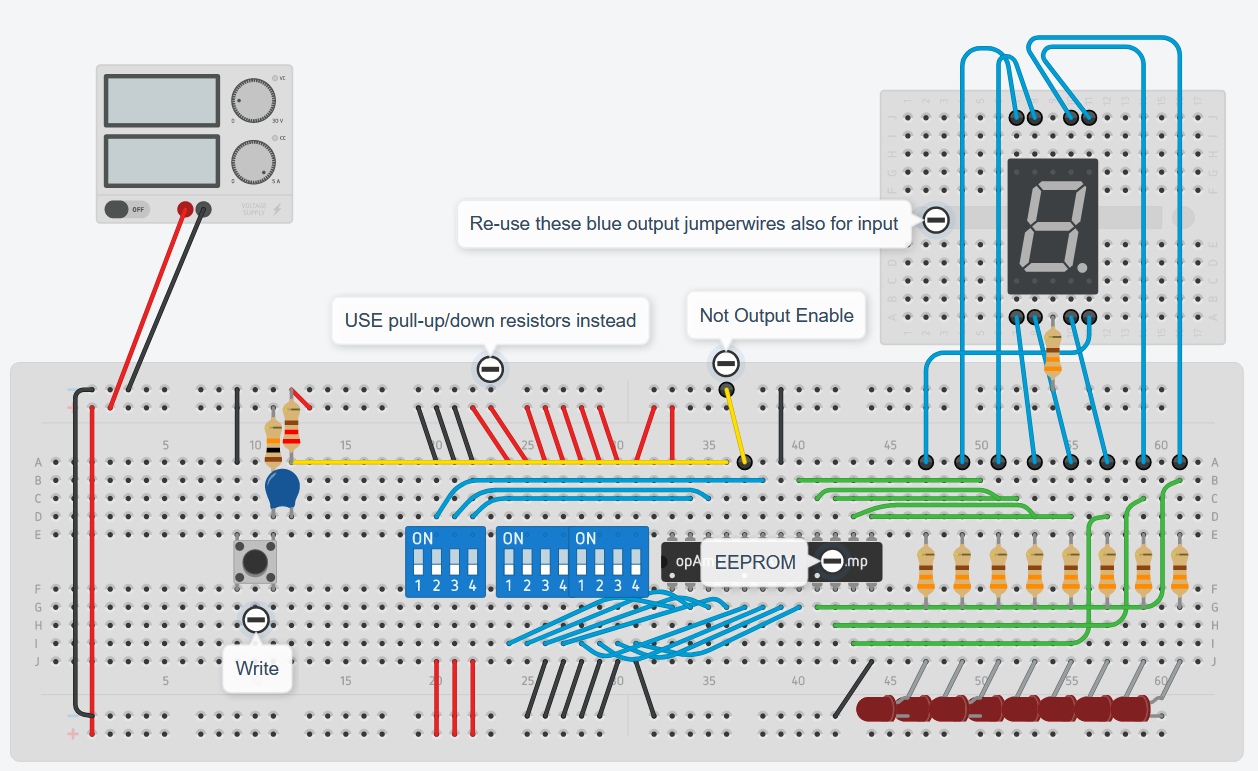

Building an 8-bit input terminal for the RAM (to manually store a program) and the alternative of inputs from the Bus

- We’ll stick a breadboard under the RAM module and above the instruction register

- We’ll use the same signal for “programming mode”/”running mode” that the address register mux uses for the input mux, where A inputs come from the 8 bit DIP switch and the B inputs come from the Bus.

- For 8 bits we need to deploy two mux chips (74LS157)

- Building steps:

- Insert the 8 bit DIP switch and the 2 mux

- Hookup power and ground pins, and both strobes of the multiplexers (pin 15) to low

- Connect one of the DIP terminals to the mux A inputs (Big Endian, MSB goes to A1, pin 2), the other terminal to ground (because then the bit is either grounded (low) or floating (high in LS chips))

- We did BIG endian for the address (most significant bit was output 1 of the MUX, pin 4), so we’re gonna do BIG endian with the data pins too.

- Connect A inputs to the bus (Big Endian)

- Connect the outputs of the mux into the data pins of the RAM (Big Endian)

- Tie both select pins (1) of both data muxes together

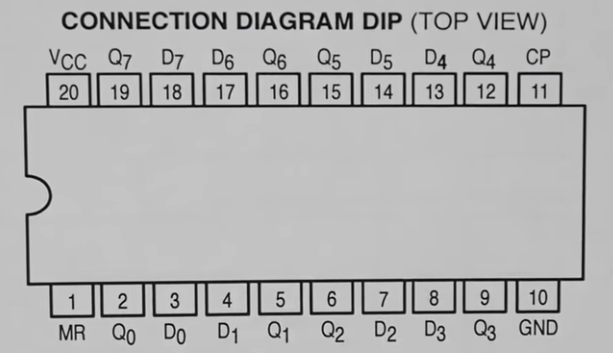

- Replace the RAM “Not Load” signal (\(\overline{WE}\)) with the output of yet another mux