Linear Algebra Cheatsheet

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Matrix operations

- Linear Transformations

- 90° rotation (counter clockwise)

- α rotation (in rad) counter clockwise

- Reflection through the x-axis

- Reflection through the y-axis

- Reflection through the line y=x

- Reflection through the origin

- Reflection through the line y = -x

- Horizontal contraction and expansion

- Vertical contraction and expansion

- Horizontal shear

- Vertical shear

- i and j are dependent

- Projection onto the x-axis

- Projection onto the y-axis

- Domain and co-domain

- Surjective (onto) and injective (one-to-one) mappings

- Composition of 2 transformations

- Transposing

- Inverse matrices

- Subspaces

- Linear Transformations

- Determinants

- Eigenvectors and eigenvalues

- Diagonalization and symmetric matrices

- Dynamical Systems

- Complex Eigenvalues

- Complex Dynamical Systems

- Orthogonal Projections

- Linear models

- Matrix operations

Matrix operations

Linear Transformations

- \(T(a+b) = T(a) + T(b)\)

- \(T(ca) = cT(a)\)

90° rotation (counter clockwise)

To do so the green arrow would have to point to (0,1) and the red arrow would have to point to (-1,0). The new values for \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) would be :

\[\vec{i}=\begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} and\ \vec{j}=\begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix}\]Resulting in:

\[T(x)=\begin{bmatrix}0 & -1\\1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x_1\\x_2\end{bmatrix}\]α rotation (in rad) counter clockwise

\[\begin{bmatrix} \cos{(\alpha)} & -\sin{(\alpha)}\\ \sin{(\alpha)} & \cos{(\alpha)} \end{bmatrix}\]Reflection through the x-axis

Here \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) would have to go from \(\color{red}{\uparrow}\color{green}{\rightarrow}\) to \(\color{red}{\downarrow}\color{green}{\rightarrow}\) That means that only \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) is changed:

\[\vec{j_{old}}=\begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} \longrightarrow \vec{j_{new}}=\begin{bmatrix}0\\-1\end{bmatrix} \longrightarrow A=\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\0 & -1\end{bmatrix}\]Reflection through the y-axis

Here \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) would have to go from \(\color{red}{\uparrow}\color{green}{\rightarrow}\) to \(\color{green}{\leftarrow}\color{red}{\uparrow}\) That means that only \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) is changed:

\[\vec{i_{old}}=\begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} \longrightarrow \vec{i_{new}}=\begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix} \longrightarrow A=\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 0\\0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]Reflection through the line y=x

This is also known as the inverse of a function. We simply have to swipe ROWS, resulting in:

\[A=\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1\\1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\]This could also be achieved with:

- rotation of 90° counter clockwise followed by a reflection in the y-axis

- or, reflextion in the x-axis followed by rotation of 90° counter clockwise

Reflection through the origin

This is simply a 180° rotation, or alternatively scale both \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) by -1, resulting in:

\[A=\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 0\\0 & -1\end{bmatrix}\]Reflection through the line y = -x

This combines a reflection through the origin with an inverse.

\[Inverse = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1\\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \longrightarrow Reflection_{origin} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1\\ -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]Horizontal contraction and expansion

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} k & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]If k > 1, then the image is stretched out. If 0 < k < 1, then the image is squeezed. If k < 0 the image is mirrored on the y-axis.

Vertical contraction and expansion

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & k\end{bmatrix}\]If k > 1, then the image is stretched out. If 0 < k < 1, then the image is squeezed. If k < 0 the image is mirrored on the x-axis.

Horizontal shear

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & k \\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]Here \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) is tranformed from \(\color{red}{\uparrow}\) to \(\color{red}{\nearrow}\) with k slope.

Which means that as we move up, the image is stretched horizontally by k units.

Vertical shear

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ k & 1\end{bmatrix}\]Here \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) is tranformed from \(\color{green}{\rightarrow}\) to \(\color{green}{\nearrow}\) with k slope.

Which means that as we move right, the image is stretched vertically by k units.

i and j are dependent

If both \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) are dependent (they can be expressed as a linear combination of the other, in this case as a scalar of the other), such as in the matrix with all 1’s, we would endup with \(\color{red}{\nearrow}\color{green}{\nearrow}\) It means that both \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\) “collapse” into each other making the image of the transformation get completly squeezed in the line that goes through both \(\color{green}{\vec{i}}\) and \(\color{red}{\vec{j}}\)

Projection onto the x-axis

The transformed image only has x-values (y remains constant 0).

\[A=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}\]Projection onto the y-axis

The transformed image only has y-values (x remains constant 0).

\[A=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]Domain and co-domain

- For Ax=b

- domain = \(R^{rows\ in\ x}\)

- co-domain = \(R^{rows\ in\ b}\)

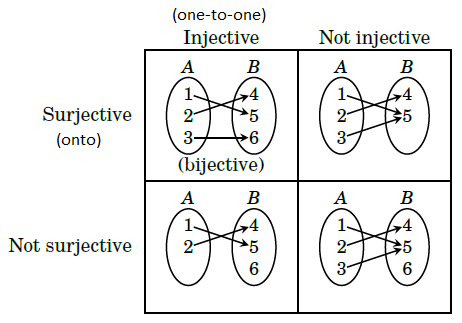

Surjective (onto) and injective (one-to-one) mappings

- A mapping \(T:A\rightarrow B\) is surjective (A is onto B) iff Range = Codomain.

- A has a pivot position in every row

- Ax = b has a solution for all b’s in \(\Bbb R^n\)

- All b’s in \(\Bbb R^n\) are a linear combination of A

- The columns of A span \(R^{n}\)

- Ax = b has a solution for all b’s in \(\Bbb R^n\)

- A has a pivot position in every row

- A mapping \(T:A\rightarrow B\) is injective (A is one-to-one with B) iff every input gets a unique output.

- The columns of A are linearly independent

- T(x) is injective (onte-to-one) iff T(X) = 0 only has the trivial solution (not being injective doesn’t have to make you surjective and viceversa)

- The columns of A are linearly independent

- A mapping is bijective if it is both, surjective and injective.

- \(T:R^n \to R^{n+1}\) is at most injective (if columns are independent)

- \(T:R^n \to R^{n-1}\) is at most surjective (if every row has a pivot)

- \(T:R^n \to R^{n}\) is is either bijective or neither surjective nor injective

Hint from the Book of Proof (Richard Hammack):

Composition of 2 transformations

Where \(A_1\) and \(A_2\) are the standard matrixes for the the 1st and the 2nd transformations respectively:

\[T(\mathbf{x})= A_2\Big( A_1\begin{bmatrix}x \\ y\end{bmatrix}\Big)\]Which results in a matrix multiplication.

Transposing

You sawp the columns for the rows (just like in excel), it’s not a 90° rotation. There are some properties:

- \((A^T)^T=A\)

- \((A+B)^T=A^T+B^T\)

- \((kA)^T = kA^T\)

- \((AB)^T = B^TA^T\)

- If A is invertible: \(T^{-1}(x) = A^{-1}x\)

Inverse matrices

- A matrix that is not invertible is a singular matrix

- An invertible matrix is called nonsigular matrix.

- \(A^{-1}A=I\) and \(AA^{-1} = I\)

- Formula to find the inverse of a 2x2 matrix:

- \((AB)^{-1} = B^{-1}A^{-1}\)

- \((A^T)^{-1} = (A^{-1})^T\)

- if A is an invertible n x n matrix, then for reach b in \(R^n\) the equation Ax = b has the unique solution \(x = A^{-1}b\)

Invertible matrix theorem

For a square n x n A matrix, these are either all true or all false:

- A is an invertible matrix

- A is row equivalent to the n x n identity matrix

- A has n pivot positions

- Ax = 0 has only the trivial solution

- The columns of A are independenet

- T(x) is one-to-one

- Ax = b has at least one solution for each b in \(R^n\)

- The columns of A span \(R^n\)

- T(x) is \(T: R^n \to R^n\)

- The transpose of A is also invertible

Subspaces

- To be a subspace of \(R^3\), a set H must satisfy:

- The zero vector is in H

- For each u and v, the sum u + v is in H;

- For each u in H, the vector cu is in H for all scalars of c.

- \(rank(A) + dim(Nul(A)) = \) number of columns in A

- rank A = number of vectors in col A

-

The zero vector is contained in every subspace, therefore all the vectorspaces has at least one vector in common and are not “disjoint” (as in not having at least 1 vector in common)

- Dot product of each row with vector x (of the null space) yields zero:

- \((Row\ A)^\perp=Nul A\)

- \((Row\ A^T)^\perp=Nul A^T \Longleftrightarrow (Col\ A)^\perp=Nul A^T\)

For an n x n matrix, iff A is invertible, then:

- The columns of A form a basis of \(R^n\)

- Col A = \(R^n\)

- dim Col A = n

- rank A = n

- Nul A = [0]

-

dim Nul A = 0

- Usually the basis for H is defined as \(\mathcal{B} = \{b_1,\dots,b_p\}\)

- The coordinate vector of x (relative to \(\mathcal{B}\)) or the B-coordinate vector of x is defined as:

Determinants

\[\begin{vmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{vmatrix} = ad-bc\]- det I = 1.

- Row exchanges:

- odd: scale determinant by -1

- even: scale determinant by 1

- Scale a row by t: the determinant becomes t * det A

- Similarly, we can factor out a scalar \(t\) from a row

- Adding one (scaled) row to another does not change the determinant

- Linearly dependent matrix has det = 0

4.\(\) If two rows are equal, the determinant is zero.

- We already know that the Rank is less than n, and therefore it is not invertible. So the determinant is zero.

- But this also comes from property 2

- If we have 2 equal rows we can switch them, which should make the determinant of the opposite sign. However, the matrix still looks the same. The only number that is equal to it’s opposite sign is 0.

5.\(\) The determinant of a triangular matrix is equal to the product of the main diagonal.

\[det \ U = \begin{vmatrix} d_1 & * & \dots & * \\ 0 & d_2 & \vdots & * \\ 0 & 0 & \ddots & * \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & d_n \end{vmatrix} = d_1d_2\cdots d_n\begin{vmatrix} 1 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & \vdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \ddots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & 1 \end{vmatrix} = d_1d_2\cdots d_n\]Properties

- det A = 0 when A is singular (not invertible)

- A is invertible \(\Leftrightarrow det(A)\neq 0\)

- \(det(AB) = det A * det B\)

- \(detA^T=detA\)

- \(det(A^{-1}) = 1/det A\)

- \(det(A^2) = (detA)^2\)

- \(det(2A) = 2^ndet(A)\)

Co-factor expansion

- You can expand either in the columns directon or in the row direction

- Choose option with more zeros

- Or bring the matrix to triangular form while accounting for all the changes in the determinant.

Eigenvectors and eigenvalues

- \(Ax=\lambda x\)

- x is the eigenvector, which CANNOT be the zero vector

- \(\lambda\) is the eigenvalue, which CAN be 0 integer.

- The “characteristic equation” is: \(det(A-\lambda I)=0\)

- Used to find \(\lambda\)

- \(E_\lambda=Nul(A-\lambda I)\)

- The vector 0 is not an eigenvector, but is an element of \(E_\lambda\)

- \(trace(A)=\lambda_1 + \lambda_2 + \lambda_3 + \lambda_n\)

- The geometric multiplicity of an eigen value is less than or equal to its algebraic multiplicity

Eigenvalue determinant properties

- \(det(A)=\lambda_1 \cdot \lambda_2 \cdot \lambda_3 \dots \lambda_n\)

- Comes from \(det(A)=det(PDP^{-1})=det(P)\cdot det(P^{-1})\cdot det(D)=det(D)\)

Eigenvalues of a reflection transformation

- If a vector is tranformed by a matrix that reflects (mirrors) all the vectors over a line that goes through a point (a,b), then there are 2 eigenvalues: 1 (if the vector is parallel to the line, that is, a scalar of (a,b) and -1 if the vector is perpendicular to (a,b))

- The eigenvector of 1 is (a,b), the eigenvector of -1 is (-b,a)

Diagonalization and symmetric matrices

Similar matrices

- A is similar to B iff there exists an invertible matrix P such that \(A=PBP^{-1}\) and hence diagonalizable.

- When A and B are similar:

- A and B have the same rank

- det A = det B

- A and B have the same charactersitic polynomial

- Have the same eigenvalues, same multiplicites

- A is invertible iff B is invertible

Diagonalizable matrices

- An n x n matrix with n distrinct eigenvalues is diagonalizable.

- An n × n matrix A is diagonalizable if and only if A has a linearly independent set of n eigenvectors (that is, P is invertible)

- \(A^k=PB^kP^{-1}\)

Symmetric matrices

- The matrix is symetric with respect to the main diagonal

- Therefore \(A=A^T\)

- All eigenvalues are real, there are n if we count the multiplicites

- the geometric multiplicity of an eigenvalue = algebraic multiplicity of such eigenvalue

- Eigenvectors of a symmetric matrix that correspond to different eigenvalues are orthogonal

- All symmetric matrices are (orthogonally) diagonalizable

- The number of positive eigenvalues is the same as the number of positive pivots

- The set of eigenvalues of A is sometimes called the spectrum of A

- The eigenspaces are mutually orthogonal (because the eigenvectors are orthogonal)

- A is orthogonally diagonalizable

Dynamical Systems

\[\cases{a_k=6a_{k-1}\ -2b_{bk-1}\\ b_k = 6a_{k-1} \ -b_{k-1}} \Leftrightarrow \begin{bmatrix} a_k \\ b_k \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 6 & -2 \\ 6 & -1 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} a_{k-1} \\ b_{k-1} \end{bmatrix}\]- \(A^k=PD^kK^{-1}\)

- \(x_k=\left(PD^k P^{-1}\right)x_0\) or, if you know the previous state of \(\begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \end{bmatrix}\) Then \(x_k=Dx_{k-1}\)

- Alternatively solve \(EigenvectorBase\cdot w=x_0\) to get the weights \(w_1, w_2\) of the linear combination of the eigenvectors \(v_1, v_2\) of A, such that: \(x_k=A^kx_0=A^k(w_1v_1+w_2v_2)=w_1\cdot\lambda_1^k\cdot v_1+w_2\cdot\lambda_2^k\cdot v_2\)

- The first step is formally known as \(x_{k+1}=Ax_k\)

- Overtime the absolute size of the eigenvalues determine:

- attracting vectors towards the origin if all absolute sizes are smaller than 1

- repelling vectors away from the origin if all absolute sizes are larger than 1

- except the constant zero trajectory

- saddle point if some absolute sizes are bigger than 1 and others smaller than 1

- Some tend towards the origin

- Some repell away

- For linear systems only the origin can be the attractor/repeller/saddle point

- Scalar vectors of eigenvectors do not attract nor repell from origin (since they are eigenvectors they continue on the same line)

Complex Eigenvalues

- Let A be a real 2 x 2 matrix with eigenvalues \(a \pm bi\) where \(b\neq 0\) and a and b are real numbers. Then there exists an invertible real matrix P such that:

- The matrix P can be constructed as

- Where v is an eigenvector associated to the eigenvalue \(a - bi.\)

-

The angle \(\theta\) is the argument of \(\lambda=a+bi\) (where \(\tan{\theta}=\frac{y}{x}\)) and \(r=|\lambda|=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}\)

-

The same way that the conjugate of an eigenvalue is another eigenvalue in the matrix, the conjugate of an eigenvector is also another eigenvector

Complex Dynamical Systems

-

Trying to do \(A^k=P\left(\begin{bmatrix} a & -b \\b & a \end{bmatrix}\right)^kP^{-1}\) is hard, because C is not a diagonal matrix

-

Instead use the property:

- Therefore \(x_k=\left(PC^k P^{-1}\right)x_0\) or, if you know the previous transformation \(x_k=Cx_{k-1}\)

- This transformation overtime is a rotation that creates:

- Spiral towards the origin if r < 1

- Spiral away from the origin if r > 1

- Elliptic (or even circle sometimes) if r = 1.

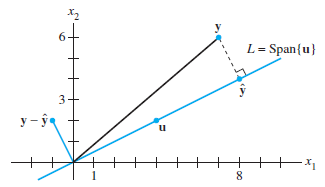

Orthogonal Projections

- The basis from set {\(u_1,u_2…\)} must be orthogonal

- The orthogonal projection of y onto W is \(\hat{y}\), which is the closest point to y from W:

- \(\hat{y}\) makes the smallest error (\(e=z=y_{orth}=y-\hat{y}\)): \(\|y-\hat{y}\|\lt \|y-v\|\)

Orthonomal basis projections

\[proj_Wy=UU^Ty\]Orthonormal matrices (called orthogonal)

- \(Q^{-1}=Q^T\)

- \(Q^TQ=QQ^T=I\)

- Rows are orthonormal too

- To make orthogonal matrix scale orthogonal columns to ortonormal

Gram-Schmidt

Given a basis \(\{x_1,\dots,x_p\}\) for a nonzero subspace W of \(R^n\):

\[v_1=x_1\] \[v_2=x_2 - \frac{x_2\bullet v_1}{v_1\bullet v_1}v_1\] \[v_3=x_3 - \frac{x_3\bullet v_1}{v_1\bullet v_1}v_1 - \frac{x_3\bullet v_2}{v_2\bullet v_2}v_2\]Then \(\{v_1,\dots,v_p\}\) is an orthogonal basis for W.

Least Squares

- If an orthogonal base is not asked for in the problem, and/or the system is inconsistent, the solution for the closest consistent y can be found with just the normal equation:

Then find \(\hat{y}\) with: \(A\hat{x}=\hat{y}\)

- Dont confuse Col A with the “least-squares line”. The least squares line is the line such that the verticial distances from a data point to the “least squares line” is minimal.

QR Factorization

- Any m x n matrix with linearly independent columns can be factored as A = QR, where Q is an m x n orthonormal basis (apply grand-schmidt of A for that) and R is the n x n upper triangular invertible matrix with positive entries on its diagonal that follows from:

- \(A=QR\)

- \(Q^TA=Q^TQR=IR\)

- \(Q^TA=R\)

- The solution for least squares: \(\hat{x}=R^{-1}Q^Tb\)

- It is faster to solve for: \(Rx=Q^Tb\)

Linear models

- The least-squares is the line \(y=\beta_0+\beta_1x\) that minimizes the sum of the squares of the residuals.

- resiudual is observed y - projected y

- residual vector is all the observed y’s - all the projected y’s (in their respectives entries)

- It doesnt matter what comes right to the coefficients (line shape, curve, etc), we can plug the data in the design matrix anyway

- Such that \(y=X\beta + \epsilon\) and: